Tim Lai argues that George Osborne's deficit reduction plan has been painful, but the right choice given the alternatives. The Conservative party’s prospective Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, faced a series of problems going into the 2010 general election: a deep and protracted global economic slump following the 2008 credit crunch, paralysed money markets, a spiralling budget deficit and rapidly rising national debt.

The credit crunch arose from the United States’ sub-prime mortgage market. From the mid-1990s, US government policy aimed to promote home ownership amongst middle and low-income groups. Regulatory lending standards were reduced, enabling riskier loans to be made. Separately, expansionary monetary policy after the 2001 dot.com crash kept US interest rates low from 2002 to 2004, encouraging borrowers into debt. As rates ‘normalised’ between 2005 and 2007, mortgage costs rose, house prices softened, over-extended borrowers on highly-leveraged loans became exposed, and mortgage defaults multiplied.

Financial institutions in the globalised secondary mortgage market caught a cold. Benign capital reserve regulations had allowed them to become over-exposed too, on the back of mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations funded by short-term inter-bank borrowing. These complicated bundles of debt were rated as safe by virtue of their diversity, but they proved catastrophically vulnerable to wholesale decline. Their value plummeted, leaving investment banks with unmanageable debt obligations and no-where to go. Unable to judge the survivability of existing or prospective counter-parties, they no longer dared lend to each other, and credit froze from August 2007, plunging the global finance sector into crisis. Government intervention followed on a massive scale, including in the UK, with a coordinated international response to prevent complete market failure; few institutions were allowed to collapse (Lehman Brothers), but many were taken over by rivals (Bears Stearns), bailed out by tax-payers (RBS, Lloyds-TSB, Northern Rock, AIG) or fully nationalized (Bradford & Bingley). Central banks also injected huge amounts of liquidity into the markets to restore the flow of credit, and they cut base rates to unprecedented levels – the Bank of England rate fell to a record low of 0.5% in March 2009.

Despite these large-scale responses, the crunch in inter-bank lending quickly spread to the real economy. Lenders retrenched, seized by institutional paralysis, reactionary risk aversion, and the need to repair balance sheets and meet new regulatory obligations to recapitalise. Faced with this credit squeeze, general uncertainty, stock-market volatility akin to the Great Depression, fragile cash-flow, household debt, negative equity, a coincident spike in commodity and food prices (which peaked in Summer 2008), and a growing risk of bankruptcy or unemployment, businesses and consumers reigned in as well.

Albeit for different reasons, the UK’s housing market had become dangerously inflated too, and became an important factor in the nation’s economic woes. Interest rates never dipped as low as in the US, but had nonetheless been attractive to borrowers since the mid-1990s at around 6%, half the 1970s / 80s average. Liberal lending criteria drew many into the net, tacitly encouraged by successive governments addicted to property-related revenues and the invigorating effect of apparently rising household wealth. Struck by contagion and credit blight, the UK housing sector crashed (prices fell by 12% from April 2008 to December 2009), followed by domestic consumer demand (spending fell by 4% over the same period). The effect was compounded from early 2009 by events in the Euro-zone, where the banking crash spawned a sovereign debt crisis in some nations, whereby over-spending governments struggled to refinance their debt or bail out their banks. These economies faired even less well than the UK, with knock-on effects upon trade. On the supply side, surviving companies turned increasingly inward, delaying new investment or hiring, cutting costs and hoarding capital, with adverse consequences for productivity and output; UK GDP fell by 6.3% between Q1/2008 and Q2/2009.

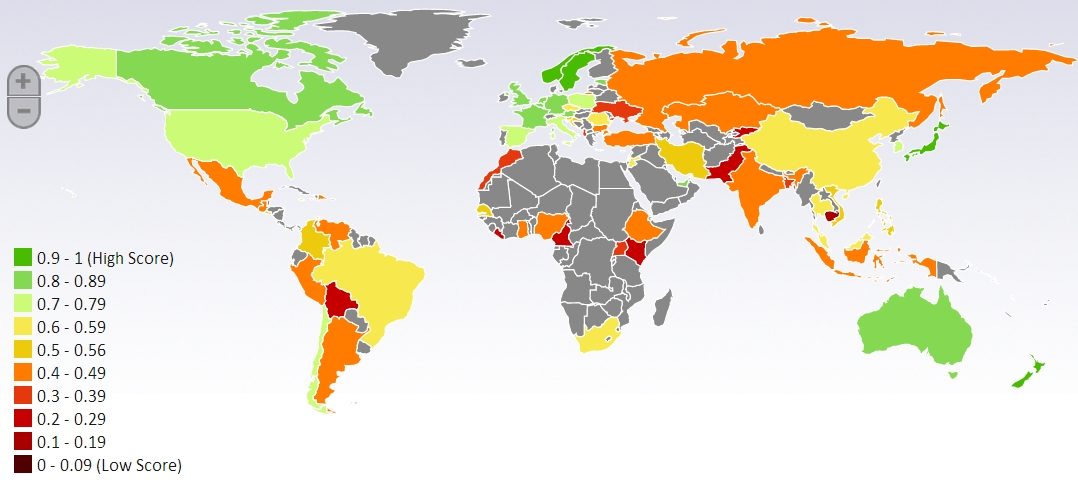

Predictably, government revenues fell in the economic downturn (from 36.3% of GDP in 2006-7 to 34.5% in 2009-10), whilst expenditures rose sharply (from 44.2% to 51.6%). Hence, in the run up to the 6 May election, the budget deficit sat at 11.2% of GDP, the fourth largest amongst OECD countries – smaller than Greece’s and Ireland’s but larger than Spain’s, Portugal’s and Italy’s (the so-called PIIGS) – and the national debt sat at 71.3% of GDP, the highest level since WW2.

Amidst this, the sitting Labour government’s expansionary pre-crisis spending plans had assumed strong economic growth, without which deficit and debt would rise further. In his April 2008 Budget, Alistair Darling, the Chancellor, was forecasting uninterrupted growth of 1¾–3% between 2008-2010, a rapid fall in inflation to 2% by 2009, a diminishing budget deficit of 2% of GDP by 2010, and national debt of less than 40% of GDP, also by 2010. Six months later, he acknowledged the extent of the UK’s fiscal challenge, but remained committed to a publicly-funded Keynesian stimulus programme, alongside expansionary monetary policy (cf Quantative Easing), low interest rates and falling commodity prices, to mitigate the effects of the ever-deepening recession confronting him. He explicitly deferred repairing the public finances to the medium-term. In his last Pre-Budget Report, in November 2009, he conceded that the economy had, in fact, contracted by 4.75% that year, he predicted above-target inflation, projected an in-year deficit of £178 billion or 12.6% of GDP, of which three quarters was structural, and he estimated that national debt would reach £1.3 trillion or 78% of GDP by 2014. But he only committed to reigning in government spending from 2011, and to halving the deficit over 4 years, with scant detail on how it would be achieved.

There was little here to worry the Keynesian devotee, for whom renewed growth would naturally close the deficit and pay down the debt. But disquiet amongst others was multi-faceted: that bureaucratically driven capital expenditure would allocate resources inefficiently, distort markets and displace private sector activity; that a globalised economy would dissipate the effect of any demand-stimuli on British productivity; that the inevitable prospect of fiscal consolidation, including through higher taxes, would dissuade consumers and businesses from being significantly stimulated; that incurring further debt rather than convincingly addressing the public finances would undermine the UK’s credit-worthiness and compound the crisis with higher borrowing costs for the government and a deeply indebted electorate (interest on the national debt stood at 4% of GDP in 2009/10, the fifth largest item of public expenditure); that a cumulative total of £25 billion in stimulus measures – which was all that even Darling felt was affordable in the circumstances – would make little impact (cf the $940 billion spent by the US federal government, the effect of which is also disputed). In short, whilst Darling’s ends may have been laudable, his Keynesian ways were questionable to many and the means he devoted were commonly held to be woefully inadequate.

Against this background, and in keeping with the Conservatives’ ‘small government’ instincts, Osborne adopted a more aggressive strategy that attacked the deficit immediately and aimed to eliminate it more quickly. His headline targets were to reduce government spending from 47% of GDP in 2009-2010 to 41% in 2015-2016, cut borrowing from 11% to 2% and begin bringing public debt down. A notable objective during the process was to preserve the confidence of bond markets and keep borrowing costs low. Ahead of the election, the Conservative Party’s manifesto had committed to: macro-economic stability founded upon savings and investment; low interest rates; effective prudential supervision of the financial markets and; at its core, a credible plan to eliminate the bulk of the structural budget deficit over the course of a single Parliament. The substance emerged on 22 June, in the new Chancellor’s emergency budget, where he described an ambitious strategy to cut public expenditure by 6.3% of GDP over four years, with more than three quarters coming from spending cuts and the balance from higher taxation. He also announced most of the major muscle moves for his strategy:

• An immediate in-year cut of £6 billion had been announced soon after the election as a nod to the markets. He supplemented this (whilst also leaving most of Labour’s pre-existing measures in place) with a public sector pay freeze, an accelerated rise in the state pension age, the elimination of middle class tax credits, a change from Retail to Consumer Price Index for calculating welfare benefits, better scrutiny of the Disability Living Allowance and restrictions on Housing Benefit. In subsequent budgets, he: cut Child Benefit for high-earners; increased public sector pension contributions; introduced ‘career average’ rather than final earnings as the basis for defined-benefit public sector pensions; placed an overall cap on welfare spending and; committed to running a balanced budget over an economic cycle. • On taxation, he increased VAT from 17.5% to 20%, introduced a bank balance-sheet levy, created a 28% Capital Gains Tax band for higher-rate earners (up from 18%) and signalled reviews on tax indexation and financial dealings as sources of additional revenue. Later, he also ramped up the Revenue’s anti-tax-avoidance operations. • To support growth, he lifted the threshold for employers’ National Insurance contributions, began a phased reduction in corporation tax from 28% to 24% (later extended and accelerated to reach 20% in 2015-2016), took steps to increase the personal income tax allowance from £6,500 to £10,000 (later raised to £10,500 – a flagship Liberal Democrat measure adopted by the coalition government), resurrected a previous link between the basic pension and earnings, and declared support to various regional infrastructure projects. This was followed by a suspension of above-inflation rises in petrol duty, the controversial reduction of Labour’s top rate of income tax from 50% to 45%, the introduction of ‘funding for lending’ and Help to Buy schemes aimed at encouraging banks to lend to small businesses and nudge developers into building new housing, and limited relief from green levies for businesses. • Finally, by way of oversight, he had already announced the creation of an independent Office for Budget Responsibility. In the Autumn of 2010, he also instigated an overhaul of the regulatory framework for the financial sector under the Bank of England, which gained wide-ranging powers for prudential regulation under its new Governor in 2013. This extensive catalogue of measures went a long way to addressing the deficit over time, but a gap remained for government departments to bridge during the Comprehensive Spending Review that followed his emergency budget. Having reaffirmed the party’s commitment to protect the health and overseas aid budgets, which represented almost 20% of all government spending, other areas faced eye-watering average cuts of 25% – up from 14% if nothing had been ring-fenced). This was later ameliorated by other savings (notably from Child Benefit), but nonetheless remained at 19%. In practice, the pain was unevenly spread, from 7.5% for Defence and 11% for Education, through 25% for the Home Office and Ministry of Justice, to over 60% for Communities & Local Government.

Osborne’s plan for fiscal consolidation was severe, and risky. Many feared it would kill off a weak recovery, plunge the economy back into recession and prolong the nation’s woes. Foremost amongst his critics was the Labour opposition. But his approach did gain the endorsement of the money markets, sovereign rating agencies and international institutions (including, initially, the International Monetary Fund), all key audiences. Subsequently, with a depreciating pound, stubborn inflation, rising unemployment, weak private sector investment, feeble productivity growth and, in 2011, the prospect of double-dip recession, he fought off strong pressure to reign back on his programme – and retrospective analysis later determined that a double-dip recession did not, in fact, occur. By the same token, he resisted further fiscal tightening in early 2013, when Moody’s removed the UK’s AAA credit rating, and when it became clear he would miss his key targets, such that the deficit will is not now expected to clear until 2018-2019, borrowing is forecast to remain above 2% of GDP until 2017-2018, and the national debt is unlikely to fall until 2016-2017.

But even as the UK’s credit-worthiness was downgraded, economic indicators began to improve, led by rising employment and followed by falling inflation, stronger growth and recovering house prices. By May 2013, the deficit had, at least, stabilised. A year later: unemployment is below 7% and record numbers have jobs; inflation is 1.6%, well below the Bank of England’s 2% target; incomes are rising faster than prices; the economy is expected to grow by 2.7% in 2014 (faster than any other major economy) and has all-but reached its pre-crisis level; and the budget deficit is down by a third and falling. In short, notwithstanding the delay in meeting his main targets, the ends to which Osborne committed himself in 2010 are largely realised or firmly in prospect. But does that make his strategy the right one?

Amongst the foremost strengths of Osborne’s approach, he maintained the confidence of the money markets and protected borrowing rates. It is improbable that the UK would ever have been unable to sell its bonds, as those nations bailed out by the troika of the European Commission, European Central Bank and IMF were unable to do during the Eurozone crisis, but a loss of confidence would almost certainly have raised the cost of government and personal borrowing, swallowing up the Exchequer’s scarce resources and compounding the financial difficulties of individual debtors and struggling businesses (the UK’s 10 year bond yield fell from 4.28% in February 2010 to a record low of 1.38% in July 2012, and stood at around 2.67% in late April 2014; by contrast, Spain’s peaked at 7.6% in July 2012 and was 4.29% in April 2014; Greece’s peaked at 48.6% in March 2012 and stood at 8.6% in April 2014). The creation of an independent OBR and the consolidation of responsibility for financial stability and prudential regulation under the BoE played to the same ‘confidence’ narrative by strengthening fiscal transparency and economic governance. The theorist (including the OECD and IMF) would also look favourably upon Osborne’s spending cuts as a more effective way to close the budget deficit than a higher taxes, and upon his increase in consumption tax as less distorting and constraining on growth than taxes on income, production or investment. But both spending cuts and higher VAT are regressive and, politically, they demanded to be offset. Raising the personal income tax allowance (and manipulating the higher rate threshold to limit the benefit to higher earners) did this, whilst also incentivising employment over welfare dependency. So, too, eliminating middle-class allowances and introducing higher-rate capital gains tax. Meanwhile, cutting corporation tax, employers’ National Insurance contributions and moderating rises in fuel duty will have supported private sector growth, albeit this effect was notably sluggish. In summary, Osborne’s package of measures seems balanced and well calibrated to deliver effect without breaking voters’ endurance. Whilst risky, it was also politically astute, underlining the Tories’ reputation for economic competence and forcing Labour toward fiscal conservatism in an attempt to shed their reputation for profligacy.

His approach has not been without its weaknesses, however. Most notably, the commitment to ring-fence health spending has severely exacerbated cuts elsewhere and distorted service provision across the board. It has also sheltered 20% of total government spending from the most rigorous examination. This may have been a political concession the Tories had to make to gain office in 2010, but it was constraining and unlikely to be repeated in 2015. Another commonly levelled criticism has been that universal pensioner benefits were left untouched. In view of dramatically improved health and life expectancy, and the less wearing nature of most modern occupations, many have also argued that Osborne should have gone further with raising the state pension age. But senior citizens are a growing constituency and the group most likely to vote. They cannot easily be ignored and, indeed, the Tories even reiterated their expensive commitment to protect the value of state pensions via the ‘triple lock’, which assures indexation by the greatest of inflation, wages or 2.5%. Elsewhere, Labour’s capital investment cuts, amounting to 1.5% of GDP, were left in place. Granted, new and important capital spending was subsequently announced (much of it using private sector money) but, amongst all else, it could sensibly have been disbursed earlier, helping to create economically conducive conditions for the recovery. In short, the government’s strategy has had its economic shortcomings, some of them quite serious, but most have been driven by political expedience or necessity; ever will it be thus.

The circumstances facing the government have also presented opportunities, some of which have been embraced more readily than others. For example, the chance to refashion and shrink government has been clear, but seems largely to have been taken ad hoc, without any central or overarching examination of what the state is for. The OBR forecasts that public sector employment will have shrunk by up to 1.1 million by 2018, spending has become more targeted and public services have been opened up to other providers; but this does not amount to a fundamental philosophical transformation. A root-and-branch overhaul of the UK’s complicated and behaviour-distorting tax code is overdue – for example, to remove the increasingly artificial distinction between income tax and National Insurance, to enhance rewards for investment and production, and to eliminate the most harmful forms of economic rent. Less punishing or stigmatising bankruptcy laws, akin to those of the United States, might encourage enterprise. And an examination of the energy sector could more faithfully price carbon emissions, evaluate the cost and maturity of emerging green technologies and agree sensible bridging strategies around nuclear generation and shale oil and gas.

But nor should the threats be underestimated that Osborne faced to his strategy. It seems likely that excess productive capacity, scarce credit, general uncertainty, risk aversion, and turmoil in the Euro-zone export market did, indeed, serve to dampen private sector investment and to delay the substitution of public sector spending that Osborne’s plan required. Faced with multiple challenges, banks also remained stubbornly reluctant to lend to business. Most indicators came to point strongly in the right direction, but his timetable had already been compromised by this earlier sluggishness. Inflation could have knocked things off track too; although fuelled by temporary phenomena, the cumulative and persistent effect could have forced an unwelcome rise in interest rates. Instead, deflation became the greater threat. Disappointing private-sector investment and a persistently fragile Euro-zone left exports weak, perpetuating a potentially destabilising trade deficit. A resurgent housing market raised the fear of a new bubble, and saving remained unattractive.

In summary, whilst imperfect, Osborne’s deficit reduction plan withstands scrutiny. At a time when others were reluctant to face (or publicly admit to) the economic challenge in prospect fro the nation, he described it as he saw it and was clear on his objectives from the outset, with respect to government spending, borrowing and debt; he laid out his timetable; and he deployed a strategy to deliver, balancing savings against revenues and using effective measures that, in many instances, had reinforcing secondary effects. But it is always difficult to prove cause and effect in real-world economics, where innumerable inter-dependent factors are at work, which cannot be evaluated in isolation. Hence, the extent to which Osborne’s actions were the cause of the positive economic outcomes that followed will always be debatable. But on the balance of rather extensive circumstantial evidence, it is reasonable to conclude that his strategy was successful.

Nor is it easy to contemplate alternatives in the absence of any meaningful counterfactual. Some present President Obama’s stimulus package in the US as the sort of Keynesian response advocated by Labour. But the effect of this federal spending was substantially diminished by the sharp cuts forced upon the states, most of which are required by law to maintain a balanced operating budget. The US, with the world’s reserve currency, also enjoys very different borrowing terms in the bond markets to the UK. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the much more severe austerity visited upon the PIIGS by the troika, in order to restore their fiscal credibility, is widely viewed to have prolonged recession and aggravated unemployment well beyond anything the UK endured (Greece, Spain and Italy remain in recession in May 2014, with Greek and Spanish unemployment still exceeding 25%). In short, George Osborne’s flawed offering may have been about as good as it could reasonably have been.