The TUC has a complaint with reality

The Trades Union Congress has a complaint it would like to make to someone about the reality of our universe. We're not sure they're going to get very far there being no central ruler but they want to complain nonetheless:

There's more to the minimum wage than 1998

One of the difficulties in economics is isolating the effects of particular actions in a very complex world. If we cut income tax this year and next year tax revenues are a little higher, it’s tempting to attribute that to the tax cut.

The difference between France and a liberal nation

We would not say, ourselves, that we are greatly in favour of the burkini and other such manifestations of Islamic prurience. Yet we would, as with people saying things we might not agree with, insist that the populace should be allowed to dress themselves in any such manner that doesn't actually frighten the animals.

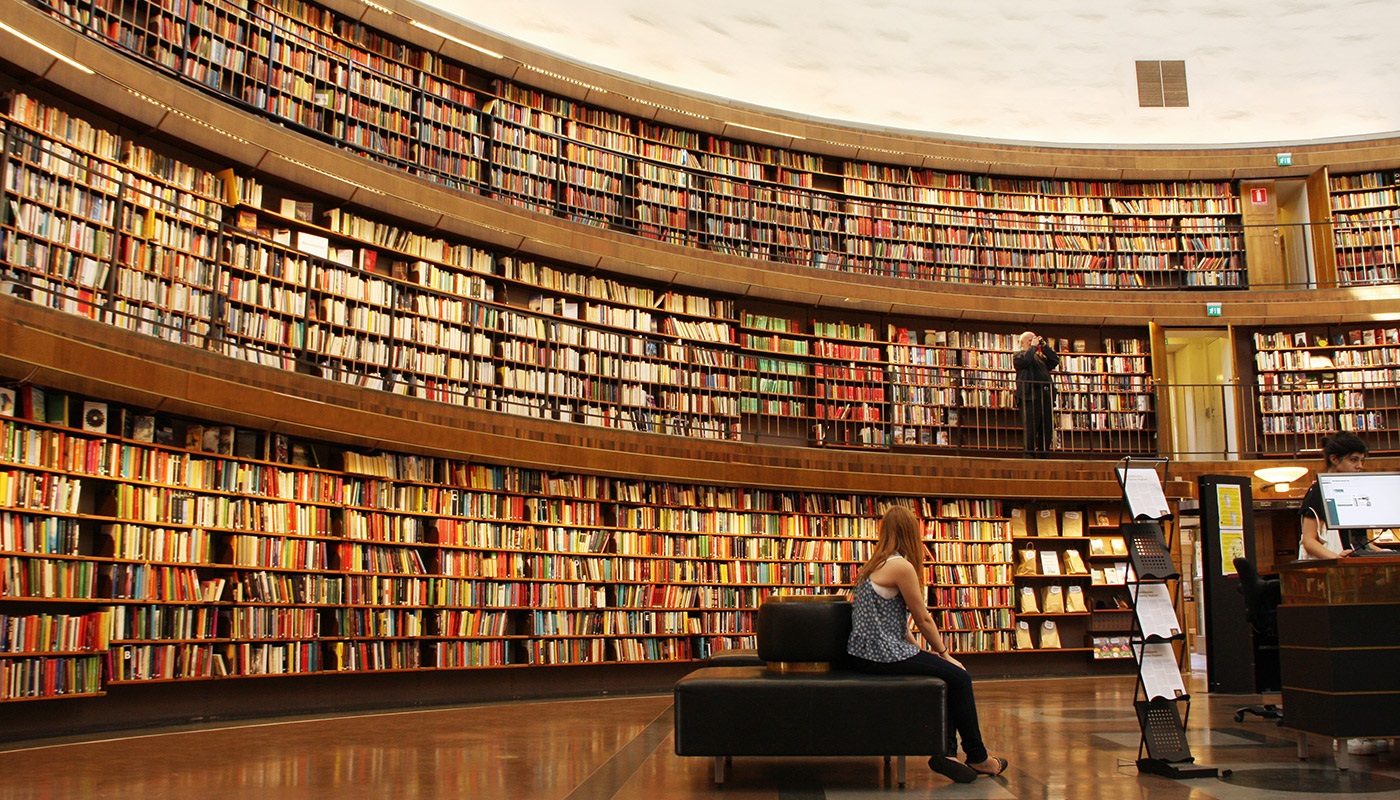

Recommended books – the other list

Almost everyone on the libertarian free-market side recommends a similar top ten books, including the classic works of Hayek, Popper, Friedman and the others. They are in my top ten, too. However, I have drawn up a second list, one of books less celebrated, but which sustain, if more obliquely, a similar philosophical outlook.