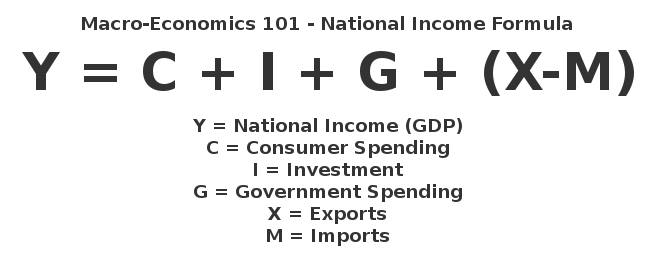

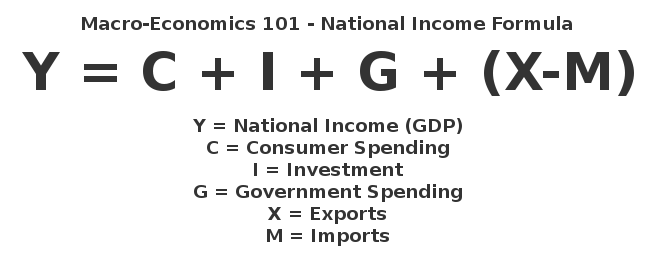

That GDP isn't a very good measure of how we're doing has been known since the concept was first pushed by Simon Kuznets coming on a century ago. It only includes monetised transactions, includes government at what it costs rather than the value it adds, doesn't discuss the distribution of income or consumption, only the gross amount and so on and on. It has its merits, in that it is also reasonably easy to calculate, something that isn't true of all of the potentially better alternatives. The really important thing to understand though is that it is not actually a measure of how well we're doing. It's a proxy for how well we're doing. And unfortunately it is becoming an ever less accurate proxy, as this new paper details:

It is also the case that zero-priced digital goods are – by definition – not counted in GDP. Some of these are advertising funded, rather than subscription funded, so the business model choice affects measured GDP – although the invariance could be restored by taking account of the imputed cost to consumers of the unwanted adverts (Nakamura and Soloveichik 2015). Zero prices and the prices of digital bundles are not accounted for in the consumer price deflators either, leading to an understatement of real growth.

Some zero-priced goods – not only products such as software, blogs, and videos, but also ‘sharing economy’ services such as house swaps or shared meals – could be considered voluntary activities, analogous to reading to children in the local school or volunteering in a charity shop. These volunteer activities are outside the conventional production boundary, just like household services.

The importance here (and the paper discusses many other reasons why GDP is getting less good as a measure) is that we're not in fact interested in production at market prices, nor cconsumption at them, at all. What we're truly interested in is how much people can consume. With physical goods we have a rough rule of thumb: the consumer surplus (that is, the value the consumer gets but which they don't have to pay for) is 100% of GDP. So, if GDP is £1.5 trillion, roughly right for the UK, we're really saying that we think that the value of all consumption, to those doing the actual consumption, is some £3 trillion. But those digital goods skew this horribly.

We measure, for example, Google's addition to GDP as being the advertising they sell here. Which, given that they sell it all from Ireland means no addition to UK GDP at all (well, OK, the wages of their support engineers do count but). But absolutely no one at all thinks that the consumption value to all of us of Google's existence is zero. Thus GDP is getting ever further out of whack with what we really want to measure, which is total consumption.

It's also true that there's no very easy answer to this either. But we should be aware of it. And for two very good reasons. Firstly, economic growth is not as slow as the standard GDP figures show us. And secondly, inequality is rather less than most think. You and I have just as much access to, and at the same price, the services of Facebook, Google and so on as Gerry Grosvenor, something that does indeed reduce the gap between the richest man in the Kingdom and us working stiffs.