The visa and the sausage

The policy making process is a messy business. It is widely and fairly quoted that “laws, like sausages, cease to inspire respect in proportion as we know how they are made.” Think tanks sit at the very start of the policy process – writing recipes for politicians to feed to the public (as well as writing recipes for the public to feed to politicians). However, polices can become adulterated as they are funnelled through the sausage machine of government. Some policies are just bad ideas – such as the creeping reintroduction of incomes policies, which dramatically and unequivocally failed in the 1970s – but some good policies fail in their implementation. At least one is failing because nobody knows it exists: the Tier 1 Exceptional Talent Visa for tech.

As Sam Shead explains at TechWorld:

As part of an effort to get more of the world's best tech entrepreneurs and software engineers to come to the UK, prime minister David Cameron announced last December that the government was going to allow Tech City UK to endorse 200 of the 1000 slots. At the time, Cameron said more overseas talent was needed if the UK wanted to overcome the skills gap that exists in the tech sector.

The Tier 1 Exceptional Talent Visa should be a fast-track for tried and tested entrepreneurs to enter the UK, but even though Tech City UK has been free to endorse entrepreneurs since April, the policy is struggling to get off the ground.

The failure is largely the result of so few people knowing the visa route even exists. I’ve spoken with plenty of entrepreneurs, recruiters and lawyers – all of whom are needed to make this policy work in practice. Most haven’t heard of this visa route and none has the information required to understand the process. There is plenty of blame to go around but Tech City UK and UKTI probably deserve the brunt of it.

The failure of the Tier 1 Exceptional Talent Visa tech demonstrates how government departments and quangos are falling short in their job of communicating policy to so-called stakeholders (for want of a better word). We can’t rely on MPs to spread the word. In a recent poll commissioned by The Entrepreneurs Network it was discovered that they are largely ignorant of current policies to support entrepreneurs.

Based upon the evidence (and my cosmopolitan biases), fiddling with the Tier 1 Exceptional Talent Visa doesn’t go nearly far enough in liberalising the immigration system. But before this great battle of ideas is won – which will encompass cultural as well as economic clashes – every failing policy is a setback.

Philip Salter is director of The Entrepreneurs Network.

On Ed Miliband's new tax on tobacco profits

Ed Miliband has decided that there should be higher taxes on the profits of cigarette companies. The argument being that smoking costs the NHS money and that thus some cash should come from the one activity to cover the other. However, that activity of smoking already more than covers the public costs associated with it. As is helpfully pointed out here:

Estimates for the amount spent on tobacco in the UK in 2011 range from £15.3bn to £18.3bn. The cost of smoking to the NHS is put at between £2.7bn and £5.2bn.The Treasury earned £9.5bn in revenue from tobacco duties in the financial year 2011-12.

When even The Guardian is pointing out the mathematical difficulties with a Labour Party leader's promises then it would be fair to say that it's not really going to fly, wouldn't it?

And that is rather the point about smoking. The activity is already sufficiently taxed that it pays for all of the public costs associated with it and more (and that's to ignore the fact that shorter lifespans as a result save the NHS money). There are substantial private costs of course: but public taxation isn't the correct way to deal with such private costs either.

Why Miliband is wrong on energy policy

This article was originally published in the Young Fabian’s quarterly magazine, Anticipations (Volume 18, Issue 1 | Autumn 2014). On this we will agree: the corporate monopoly dominating the UK energy market needs to come to an end. Currently, British customers have a total of six firms to choose from in the energy market, all of which offer very limited price distinctions.

And those prices keep going up. Since 2010, gas and electricity rates have risen by three times the rate of inflation (10.2% between 2010-2013). Quite rightly, the Big Six are constantly under attack from very political party in the UK for over-charging customers and raising retail prices, even when wholesale costs fall. With such little competition in the energy market, mega-firms can charge extortionate prices, and customers have no choice but to pay the bill.

Another point of agreement: a change in government regulation is key to breaking up this monopoly. Both Labour and Conservatives acknowledge that government regulations, like Ofgem, aren’t holding the Big Six accountable for what they charge customers. Over the past few years, party leaders have come up with new variants of the Regulatory State to combat the problem. Most recently (and most misguidedly) Ed Miliband has advocated for a government-mandated freeze on energy prices, which would force firms to fix their prices for 20 months, regardless of future changes in market conditions.

Why is this misguided? Let’s put aside Miliband’s refusal to acknowledge the costs that are loaded on to energy companies by the state (ie: requirements to source energy from renewables), which in turn, gets pushed onto the customer and focus on a second, more important point: Miliband’s policy proposals reinforce the energy monopoly.

It’s near impossible to create a market monopoly without help from the ultimate monopoly; that is, competition in the market place is so often drowned out, not by competitors, but by the state.

The energy sector is a prime example of well-intentioned government regulation gone awry. The sector is regulated so heavily, through both onerous compliance requirements and heavy taxation, that it is near impossible for any budding energy firm to compete with the Big Six. In its effort to stop energy firms from over-charging customers, the state has effectively regulated all competitors out of the market, re-enforcing the monopoly it was trying to prevent.

The bureaucratic, slow-moving nature of government bodies means that they are not equipped to understand or anticipate the unpredictability of market prices on energy. The security of energy supplies, complexities of long-term contracts, and real commodity costs are often dismissed by politicians who have made unsustainable, politically motivated promises to voters. Whilst the Big Six have no incentive to bring energy prices down when they can, a Labour prime minister would have no incentive to bring the prices up even when he must.

Britain needs appropriate, scaled back monitoring of the energy market that removes ‘safeguards’ for the Big Six’s market share and introduces healthy competition in the market place. A less-regulated system where consumer choice dictates the real price of energy would see monthly bills drop. But piling price fixation on top of bad regulations will produce a lot of heat and very little light.

Two cheers for technocracy

Who needs experts? The minimum wage was once an example of the triumph of technocracy, where decisions are delegated to experts to depoliticise them. The Low Pay Commission was set up to balance competing priorities – increasing wages without creating too much unemployment. If you were a moderate who thought the minimum wage was a good way of boosting low wages, but recognised that it might also create unemployment, the LPC gave you a middle ground position. (For what it’s worth, I’m an extremist.)

That technocratic settlement also allowed politicians to, basically, safeguard against an ignorant public. By delegating decisions like this to experts, bad but politically popular policies could be avoided. Relatively well-informed politicians could avoid having to propose bad policies by depoliticising them.

Other examples of this include NICE’s responsibility for deciding which drugs the NHS should and shouldn’t provide, and the Browne Review that recommended student fees, which had cross-bench support. The old idea that “you can’t talk about immigration” comes from an informal version of this – everyone in power knew that people’s fears about the economics of immigration were bogus, so they were basically ignored.

But that technocratic settlement now looks dead. Labour has now made a specified increase to the minimum wage part of its electoral platform, following George Osborne’s lead earlier this year. That means that voters will have to choose not just between two rival theories about the minimum wage, but two competing sets of evidence about whether £7/hour or £8/hour is better, given a wage/unemployment trade-off.

Whether voters are self-interested or altruistic doesn’t really matter. A self-interested low wage worker would still need to know if a minimum wage increase would threaten her job; an altruistic voter would similarly need to know a lot about the economics of the minimum wage and the UK’s labour market to make a judgement about what level it should be.

And of course the minimum wage is just one of dozens, if not hundreds, of questions that political parties offer different answers to that voters have to make a judgement about.

In practice this does not happen. Voters are very uninformed about basic facts of politics, and are almost entirely ignorant about economics, which almost everyone would agree would be necessary to make the correct judgement about something like what the minimum wage level should be (even if they didn’t agree on which theories and evidence was relevant). Even the use of rules-of-thumb such as listening to a particular newspaper or think tank (ha) will suffer from the same problems.

Voters, then, face a nearly impossible task. Assuming they are bright, well-intentioned, and believed that it was important for them to cast their vote for the party that would have the best policies, they would have to amass an enormous amount of information to make the right decision on all the questions they, in voting, have to answer.

So voters are trapped. They cannot know what minimum wage rate is best any more than they can know what drugs the NHS should pay for. They are, empirically, very unaware of basic facts, but they would find it hard to overcome that even if they wanted to.

Does democracy make us free? Maybe, but it’s the freedom of a deaf-blind man – we can choose whatever policy we want, without any idea about what those policies will actually do. So, if the alternative is more direct democracy like this, maybe technocracy isn’t so bad.

The end of an auld West Lothian song

Labour leader Ed Miliband is currently refusing to back any such plan, calling it a 'back of the envelope constitutional change'. He has a point: Westminster politicians are remarkably cavalier about how they change the UK's constitution. A small public company cannot change its rules just on a majority vote of the directors, so why should a large government be able to change its rules on a simple majority in Westminster? But his real concern is to ensure that the large number of Labour MPs that Scotland sends down to Westminster can still vote on everyone else's business, the 'West Lothian Question'.

The impish Alex Salmond will be chuckling at the stooshie he has created. Some say we should devolve powers down to the English cities and local authorities. Others say we need a proper English Parliament. A few talk about barring Scottish MPs from voting on English-only laws.

But devolution of power to the local authorities is a non-runner. We have been promised it for decades, but it has never really happened, and nobody trusts that it will now. As for an English Parliament – well, we have seen the expense of the Scottish one (the extravagant building alone cost ten times its original estimate) and its notoriously poor quality (stuffed, inevitably, with failed local councillors and superannuated MPs).

The simple solution to devolution, all those years ago, would have been to form English, Scottish and Welsh parliaments out of their respective Westminster MPs; and have them meet at Westminster in the mornings on their own country business, then together on UK business in the afternoon. Yes, there will be a few arguments about which matters are 'UK' and which are 'English'. But the solution is costless, and without adding an extra tier of government, you get home-grown politicians of some quality deciding home-grown issues. It is the obvious solution for England. And the end of an auld West Lothian song.

£8 minimum wage hype: political trick, economic disaster, moral outrage

Britain’s Labour Party leader Ed Miliband says that a Labour government would boost the national minimum wage to £8 an hour, an increase of about £60 per week, by 2020. He says the UK economy is booming, and the low-paid should get a bigger share of it. Actually, at present rates of growth, the minimum wage will be close to £8 in 2020 anyway, so this is a one of those political sensations that doesn't amount to much. Even so, it is foolhardy now to commit UK businesses to pay any specific figure in 2020, since anything could happen in the meantime.

The minimum wage gets unthinking politicians (and not just Labour leaders) dewy-eyed. 'We can't have people being paid a wage that isn't enough to live on.' 'Businesses should pay their workers more, and take less profit.' 'The minimum wage hasn't killed jobs as the doomsayers say.' You know the story.

In fact, high minimum wages do destroy jobs. in particular, they destroy those starter jobs, the low-paid, temporary jobs that once gave young people their first step on the jobs ladder – pumping petrol (as I did), stacking bags in supermarkets, ushering people to their seats at the flicks. Now those jobs don't exist, because they are not worth the minimum wage (plus all the National Insurance and the burden of workplace regulation that goes with them – a particular burden on small firms). So we have a million young people out of work.

As for profit, try using that argument on anyone running a small business, already weighed down by taxes, rates, and regulation. Often they are getting less than their lowest-paid employees, and working longer hours for it Higher minimum wages mean they can afford to employ fewer people, or provide less generous perks and conditions.

I don't want to live in a country where people can't afford to live on what they take home either. That is why we have a welfare system, to top up the earnings of the lowest paid. We need a negative income tax – above the line, you pay tax, below the line, you get cash benefits – structured so that you are always better off in work than out of it. A paying job, even a low-paid job, is the best welfare system the human mind can devise.

And we must take low-paid people out of tax and national insurance entirely. Then more small firms could afford to take on more low-skilled workers and give them that first step on the jobs ladder.

If we could simply vote ourselves higher pay, why stop at £8? Why not fix the minimum wage at £800 an hour. The answer is obvious. The only people who would be worth that amount to anyone would be a few Premier League footballers, rock stars, investment bankers and high-class hookers. The rest of us would be out of a job.

The minimum wage does no harm to people who are already earning it, though it does them no good either. But it does positive harm to those earning less, or those who cannot get a job at all. The former will be let go, or will have to endure worse conditions; the latter will find it very much harder to get a job. And all that, of course, has already happened.

Quelle Surprise: Nick Stern wrong again

We've yet another attempt from Nicholas Stern to persuade us all that beating climate change would actually be good for the economy. Fortunately we've also got Richard Tol around to tell us what's really going on here:

The original Stern Review argued that it would cost about 1% of global GDP to stabilise the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases around 525ppm CO2e. In its report last year the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) put the costs twice as high. The latest Stern report advocates a more stringent target of 450 ppm and finds that achieving this target would accelerate economic growth.This is implausible. Renewable energy is more expensive than fossil fuels, and their rapid expansion is because they are heavily subsidised rather than because they are commercially attractive. The renewables industry collapsed in countries where subsidies were withdrawn, as in Spain and Portugal. Raising the price of energy does not make people better off and higher taxes, to pay for subsidies, are a drag on the economy.

Just not impressed there is he?

There are some eminently sensible things that could be done, things that would have the effect of reducing climate change into the future. Poor and oil producing nations throw $600 billion a year in subsidies at fossil fuel use for example. Stopping that would be a sensible thing to do: but it would be a sensible thing to do simply because it's a sensible thing to do. The effect on climate change is just an added benefit.

But the most important part of this latest report is this:

“Well-designed policies … can make growth and climate objectives mutually reinforcing,” the report claims.

Yes, that's entirely true. But as Tol also points out:

But low-cost climate policy is far from guaranteed – it can also be very, very expensive. Europe has adopted a jumble of regulations that pose real costs for companies and households without doing much to reduce emissions. What is the point of the UK carbon price floor, for instance? Emissions are not affected because they are capped by the EU Emissions Trading Systems, but the price of electricity has gone up.

There's an awful lot of weight resting on that "well-designed" there. In fact, absolutely every report, yea every single one, that has concluded that we'd be better off trying to avert climate change than to go through it has been running the numbers on the politicians using sensible methods of aversion rather than not sensible ones. And yet when we see what those same politicians actually enact on that evidence base they're not sensible policies. Thus the justification they're relying upon doesn't in fact exist.

Of course poverty traps exist: but they're possible to escape

Over at The Economist some musing on whether there really is a poverty trap that developing economies can get stuck in. and the answer is yes, of course there is: but also that it's potentially possible to escape such traps.

Over at The Economist some musing on whether there really is a poverty trap that developing economies can get stuck in. and the answer is yes, of course there is: but also that it's potentially possible to escape such traps.

DO POVERTY traps exist? Academics seem to think so. According to Google Scholar, so far this year academics have used the phrase “poverty trap” 1,210 times. (Paul Samuelson, possibly the greatest economist of the 20th century, was mentioned a mere 766 times). Some of the most innovative work in development economics focuses on how individuals' lowly economic position may be perpetuated (geographical and psychological factors may be important).

But, says a new paper by two World Bank economists, the idea of poverty traps may be overblown. They focus on national economies and present some striking statistics. In the graph below, a country that manages to get to the left side of the line has seen real per-capita income improvement from 1960 to 2010.

So that's the empirical evidence. But there's also a basic logical point that we can make.

Three hundred years ago all countries were poor. Now some countries are not poor and some countries still are. It's thus logically certain that it is possible to escape whatever poverty traps there are. For some places have done it. It's also equally true that there must be things that prevent that economic growth from happening for some places haven't had that economic growth. Thus we can assert, without possibility of contradiction, that sure, there are poverty traps but there's nothing inevitable about them at all. It is possible to escape for some have done so.

Central banks cause low interest rates, but not by lowering interest rates

The Bank of England slashed its discount rate ('Bank Rate') to 0.5% in its 5th March 2009 meeting in response to the growing recession, hoping to stimulate demand. Its discount rate is the rate it lends out to commercial banks—and a lower rate is believed to raise economic activity, whether through expectations, extra nominal income or increased lending. It has left it there ever since, and indeed, because of the 'Zero Lower Bound' on interest rates it has turned to other tools to try and bring about an economic recovery—a recovery which is only just setting in properly. When the Bank moves its key policy rate, commentators talk about it hiking or cutting interest rates; on top of this, we've seen extremely low effective interest rates in the marketplace; together this makes it reasonable to believe that the central bank is the cause of these low effective rates.

There are lots of reasons to doubt this claim. In a previous post I pointed out that the spreads between Bank Rate and market rates seem to be narrow and fairly consistent—until they're not. I made the case that markets set rates in an open economy. And I argued that lowering Bank Rate or buying up assets with quantitative easing (QE) may well boost market rates because they raise the expected path of demand, the expected amount of profit opportunities in the future, and thus investment.

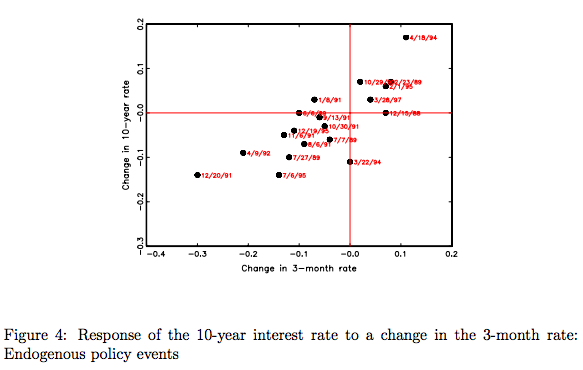

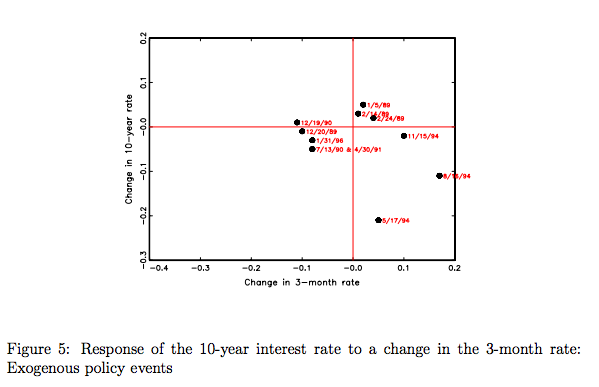

Since then I came across an elegant and compelling explanation of exactly why this is. In a 1998 paper, Tore Ellingsen and Ulf Söderström show that this is because some monetary policy changes are purely expected and 'endogenous' responses to economic events, whereas some monetary policy changes are unexpected 'exogenous' changes to the central bank's overall policy framework (like raising or lowering the inflation rate that markets believe they really want).

When changes are expected, market rates keep a tight spread around policy rates; when changes are a surprise, cutting Bank Rate actually results in higher interest rates in the marketplace.

To identify which changes were exogenous (surprises) and which changes were endogenous (expected) Ellingsen and Söderström looked at market commentaries in the Wall Street Journal the day after policy events—where the Fed decided whether to change or maintain its current policy rate. When traders they interviewed were surprised or disappointed by the move (or lack of move), they judged it exogenous—when traders explained the Fed's move in terms of changes in economic data they judged it endogenous.

This neatly explains why raising Bank Rate would not shut off bubbles (as an aside: a recently-published paper finds that tight, not easy money, is more closely associated with bubbles) and house price booms and so on. Cutting Bank Rate would raise market rates if it changed markets' perceptions of what target the Bank of England is working towards (i.e. made them think it wanted higher inflation). Conversely, if the Bank had decided not to look through high supply-driven inflation, and thus surprised markets by running tighter than expected policy, this would have been likely to push rates even lower.

The best way to get rates back to normal territory, thus incentivising firms to economise on investment projects and put cash into only the very best, is to make sure the economy doesn't suffer the effects of what Hayek called a 'secondary depression'. And the best way to ensure that is to implement something we might call a 'Hayek Rule' after the monetary policy he proposed—stabilising MV (the money supply x velocity, equal to aggregate nominal income). Recent work has shown that we get less creative destruction and capital reallocation in slumps as opposed to healthy growth periods.

Firm expectations now mean that setting this at zero, as he proposed, would have a very costly intermediate period while firms reset their plans—setting it at the rate consistent with 2% inflation (roughly 5%) would be more appropriate. Perhaps in the long run it could come down. But without a stable macroeconomic environment, capitalism cannot create the wealth that makes it so widely and dynamically successful.

The new population estimates are already being misunderstood

New estimates of future population size have only been out a day and already they're being misunderstood. Firstly they're being misunderstood by the people who actually made them:

Rising population could exacerbate world problems such as climate change, infectious disease and poverty, he said. Studies show that the two things that decrease fertility rates are more access to contraceptives and education of girls and women, Raftery said. Africa, he said, could benefit greatly by acting now to lower its fertility rate.

Piffle, stuff and nonsense. It's a well known finding that access to contraception drives, at most, 10% of changes in fertility. It's the desire to limit fertility which, unsurprisingly, drives changes in fertility. And the education of girls and women, while highly desirable, is a correlate, not a cause, of declining fertility. Economies that are getting richer can afford to educate women: economies that are getting richer also have declining fertility. It's the getting richer that drives both.

But that's not enough misunderstanding. We've also got The Guardian displaying a remarkable ignorance on the subject:

Many widely-accepted analyses of global problems, such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s assessment of global warming, assume a population peak by 2050.

That's not just piffle that's howlingly wrong. The IPCC assessments do not assume any such damn thing. For example, the A2 family, which is the family that the entirety of the Stern Review is based upon (and yes, it's one of the four families used by the IPCC) assumes a 15 billion global population in 2100. That is, it assumes a significantly larger population at that date than even these new estimates do. But you can see how this is going to play out, can't you? Population's going to be larger therefore we must do more about climate change: when in fact these new estimates show that population is going to be smaller than the work on climate change already assumes.

As we might have said here before a time or two we don't mind people being misguided in their opinions and thus disagreeing with us. We pity them for their mistakes of course, but that's as nothing to the fury engendered by people actually being ignorant of the subjects they decide to opine upon.