Government grants always end up doing this: so let's not have government grants

We don't share the reason why these people are outraged but we do share the outrage:

Snack food and confectionery companies, including Nestlé and PepsiCo, are paid substantial government subsidies to help them make products that will damage the nation’s health, according to charities involved in heart attack prevention and obesity.

Mondelez, which split from Kraft and owns the Cadbury’s brand, was given nearly £638,000 by Innovate UK – formerly known as the Technology Strategy Board – from 2013 to 2015 to help the multinational giant develop a process to distribute nuts and raisins more regularly in its chocolate bars.

Nestlé received more than £487,000 to invent an energy-efficient machine for making chocolate, while PepsiCo was awarded £356,000 to help develop new ways of drying potatoes and vegetables to make crisps.

Given that people seem to like chacolate and crisps if taxpayers' money is going to be splurged on food companies then it might as well be on food that the taxpayers enjoy. So, to that particular criticism we offer a heartfelt "Meh".

Our outrage is concentrated upon the splurging and waste of taxpayers' money. Even, perhaps, the illogic of the attempt to defend it:

Innovate UK says the money is to make the companies’ food processes more energy-efficient and reduce their carbon footprint. In the case of Mondelez, for instance, a better way of distributing nuts in chocolate bars would mean that fewer nuts have to be bought by the company, reducing the amount of transportation used.

“The goal of the projects highlighted was to help reduce emissions and water usage in food processing,” said a spokesman. “These large firms produce a lot of food, which uses a lot of energy, so to make a difference we need to work with those large companies to help reduce their carbon footprints.”

The UK does now have a system that largely approxiamtes to a carbon tax. Therefore those carbon emissions are already internalised in the decision to transport or not transport more nuts. What this means is that the provision of a grant is in fact a complete waste of money, a reduction in the general wealth of the human species.

Think it through this way. Reducing the number of nuts purchased and or transported might well reduce the costs to the chocolatier. Against which are the costs of reducing those purchases and transporting. Only if the benefits of less purchasing and transporting outweigh the costs of doing so is the process as a whole value generating and wealth enhancing. The company itself, as a profit making institution, looked at this and decided it was not. Thus the requirement for the subsidy to get them to do this. That is, the very fact that there is a subsidy proves that (because, as above, the emissions costs are already internalised) this is wealth destruction.

The point and purpose of our paying taxes in order to stimulate innovation in the UK is not for the orgainsation spending the money to make us poorer in aggregate. Therefore let us abolish this organisation which is making us all poorer through its actions.

Economic Nonsense: 26. People lack the knowledge and ability to serve their own interests

There is an implicit assumption behind this claim that someone else does have the knowledge and ability to serve people's interests better than they can do so themselves. This is dubious, to say the least. People know more about their own character, about their circumstances and priorities and the things that they value. They also care more, for the most part, than others do. It is true that people are sometimes ignorant of such things as the consequences of their lifestyle choices, but information is freely available in the media. Scarcely a day passes without news items about the various types of food we eat or the benefits of moderate exercise. In newspapers and on TV, radio and the internet, there are stories about diet and drinking, smoking and exercise. People can pay attention to this information if they wish.

Even on more complicated issues such as pensions land life assurance, there is help available from commentators explaining the different options and giving advice. No-one is on their own on such matters because assistance and explanation are freely available from widespread sources.

Sometimes people make choices for short-term gratification at the expense of greater gain in the longer term. In a free country they are allowed to do this. It is possible that some people lack the willpower to sacrifice present comfort for future rewards. This does not give anyone else the authority to take the decisions out of their hands.

Middle class people have notably longer time horizons than their working class counterparts, meaning they are more ready to do things now that will benefit them in the future. They have different priorities, but nothing in this gives them the right to impose their priorities on others. When people make their own decisions about what they do, they are acting as adults, free to take actions and to accept the consequences they bring. When others take those decisions for them and impose their own priorities, they are treating people as children unable to look after themselves.

Who knew? Property rights protect the environment?

Something to put into our "Cor, Blimey, I never knew that Guv'" files.

As the hunting industry has grown, so have the numbers of large game animals that populate South Africa’s grasslands. In other parts of Africa, including Kenya and Tanzania, the opposite has been true: Large mammal populations have been decimated as farms and other human activities encroached on wild areas. But South Africa is one of only two countries on the continent to allow ownership of wild animals, giving farmers such as York an incentive to switch from raising cattle to breeding big game. ‘‘My first priority is to generate an income from the animals on my land, but conservation is a by-product of what I do,” York says.

Or perhaps this should be in our file marked "Blindingly obvious things that everyone should know".

The way to make human beings preserve something is to make the preservation of that something valuable to said human beings. If people are allowed to own the big game on their property, and also to monetise that ownership, then there will be more big game in those places that allow such practices. Thus, if you desire that there should be more big game you should support private property and the hunting of it.

After all, the private ownership of cows by farmers has not created a shortage of cows, has it?

And this speaks to that problem over elephants too, does it not? Elephants are valued for their ivory. Currently it is not legal to trade in ivory: meaning that elephants have no value except to those who will and do flout the law on ivory trading. Allowing ivory to be bought and sold would lead to the farming of elephants for their ivory. And thus more elephants.

So, what do people want? The moral purity of not allowing ivory to be sold or more elephants?

The Good Old Days are right now

You can't make people happy by law. If you said to a bunch of average people two hundred years ago "Would you be happy in a world where medical care is widely available, houses are clean, the world's music and sights and foods can be brought into your home at small cost, travelling even 100 miles is easy, childbirth is generally not fatal to mother or child, you don't have to die of dental abcesses and you don't have to do what the squire tells you" they'd think you were talking about the New Jerusalem and say 'yes'.

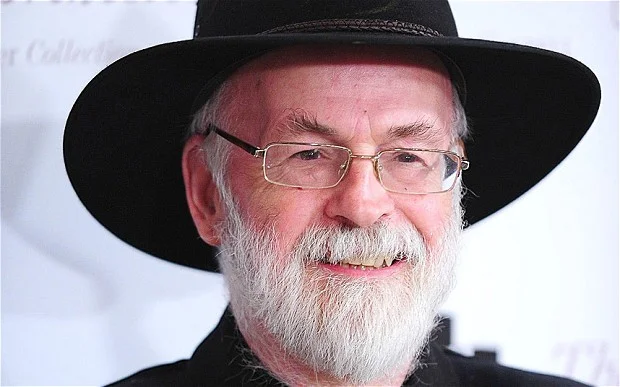

Sir Terry Pratchett. 1948-2015.

If you doubt this in the slightest manner then download the historical GDP per capita figures from Angus Maddison. Note that the numbers are in modern currency (well, 1990s currency) and marvel at how poor the past was. The average Englishman in 1600 had perhaps $3 a day of modern money to live on all told. The average Congolese has that today.

The myth of owing future generations

If you’re like me you’ve no doubt heard with great frequency the assertion that we owe it to future generations to make huge sacrifices in the present for the sake of the unborn, and that anyone who fails to accede to this maxim is bordering on moral turpitude. I find the argument that we are somehow indebted to our future generations quite absurd. Yes, of course we ought to be responsible citizens, and always be the least wasteful we can be, but the position that we have a moral duty to live as carefully as we can for their sake strikes me as a strange one to take. I think this view fails to consider one key thing – the enormous riches that the unborn will inherit from us. Look at the blood, sweat, toil, imagination and innovation that came from our ancestors to give us the kind of life we have today. As we keep increasing our skills and our ingenuity we bestow ever-greater riches for future generations.

Suppose I have a baby girl in a year's time, and I still live in the UK. Think what that child will inherit on the day of her birth: she enters a world in which she already has rich pickings of food, drinking water, roads, planes, and the luxury of plenty of leisure time. She also has a stable government, property rights, career opportunities, hospitals, entertainment, and thanks to the Internet, she has access to just about every fact that human beings have ever discovered, and to a vast proportion of other minds who she would otherwise have little chance of meeting.

Most importantly, though, she enters a world in which she'll be wealthier than any generation that has ever lived, a world in which she has the lowest chance of being involved in war, and a world in which the free market, science and technology will give her a quality of life unimaginable 250, 100, or even 50 years ago. All this she has inherited from this current generation and everybody's contributions that preceded them. So before people hastily wed themselves to the viewpoint that we are going to burden future generations with a partially ruined planet and legacies from our own carelessness, let's have a reality check and remember how the rich scientific and economic pageant of our past and present is a pageant from which future generations will benefit. When we express it in those terms, all this talk of our owing future generations is shown to be, at best, an exaggeration, and at worst, a laughable misjudgement.

Notice this irony too. Many on the left are always going on about redistributing wealth from the rich to the poor when considering people who are alive. Why, then, do they adopt the opposite approach to people who are going to be much richer than us? When it comes to wealth, prosperity and well-being, just as being born in 2014 is much more of a blessing than being born in 1914 – being born in 2064 or 2114 will (in all likelihood) be much more of a blessing than being born in 2014. Making sacrifices now for the unborn future generations is to transfer wealth from the presently alive poorer group to the unborn richer group – the very opposite of what those on the left support when the groups in question are alive in the present day.

I talked about what a great life my new daughter would be born into if she lived in my home city. I'm aware, of course, that these luxuries are not enjoyed throughout many parts of the world. If she was born in Ethiopia or Somalia the same couldn’t be said of her blessings. But ironically, the answer to this issue is the answer that shows why we should focus primarily on people suffering in the here and now. Efforts and costs expended for future people not yet born are efforts and costs that are potentially taken away from Ethiopians or Somalis now. Unless you think that Ethiopians and Somalis of a few decades time are going to be worse off then present day Ethiopians and Somalis (and if you do you're probably wrong) then deferring future considerations in favour of present day crises is both the right and most logical thing to do.

Because future generations are going to be more prosperous than us, and because it is both unethical and unwise to prioritise unborn prosperous people over present day plighted people. The trade-off between focusing on the present life lived by people of today against the future lives lived by people who are going to be our descendants comes down heavily in favour of focusing on the present life lived by people of today, as the prosperity and advancements enjoyed through the free market and through science continues to lay down the foundation of better well-being for those yet to be born.

Flexible work hours may be the key to solving wage gaps

A paper from the American Economic Review thinks it has some more insight into the cause of the gender wage gap. It’s not sexism, employer discrimination, or really even children. It’s the flexibility (or lack there of) of work hours.

The converging roles of men and women are among the grandest advances in society and the economy in the last century. These aspects of the grand gender convergence are figurative chapters in a history of gender roles. But what must the “last” chapter contain for there to be equality in the labor market? The answer may come as a surprise. The solution does not (necessarily) have to involve government intervention and it need not make men more responsible in the home (although that wouldn’t hurt). But it must involve changes in the labor market, especially how jobs are structured and remunerated to enhance temporal flexibility. The gender gap in pay would be considerably reduced and might vanish altogether if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who labored long hours and worked particular hours. Such change has taken off in various sectors, such as technology, science, and health, but is less apparent in the corporate, financial, and legal worlds. [Emphasis mine.]

The data from this paper is fascinating, and challenges quite a few pre-conceived notions we have about women in the work place. For example, we often think of jobs in the sciences, medicine and maths as being most off-limits to women, but in fact, women make up roughly half of today’s medical graduate enrolments, and actually women lead men in study areas including biological sciences, optometry, and pharmacy.

What’s even more interesting is that the gender pay gap is at its lowest in the tech and science industries. The gap begins to widen when you look at the health industry, and it spikes when you look at the business industry.

The paper, “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter” argues that this is because the tech and science industries are more suited to flexible work hours, presumably because the quality of one's work output is based on results; whereas the business industry demands the constant slog of long work hours and 'face-time' - things which their clients have come to expect, and things that can be much harder for women to do if they are trying to manage both a family and a job at the same time. Claudia Goldin, author of the report, notes "a flexible schedule often comes at a high price, particularly in the corporate, financial, and legal worlds...there will always be 24/7 positions with on-call, all-the-time employees and managers, including many CEOs, trial lawyers, merger-and-acquisition bankers, surgeons, and the US Secretary of State. But, that said, the list of positions that can be changed is considerable."

Workplace culture has been changing for years– jeans, pets, and company-sponsored Red Bull fridges are becoming widely established. A move towards flexible hours is becoming more relevant too, especially in some of the most innovative industries. Perhaps our best bet to solving wage gap issues is to encourage employers to adopt more flexibility (for both men and women) in the many industries that could suit, and even benefit, from it.

Another little proof that Gary Becker was right

Gary Becker made the point that discrimination (on race, sex etc grounds) was expensive to the person doing the discriminating. If you won't hire people because of their sex or gender, say, then you will be missing out on people of that race or gender who have the talents you're looking for. The implication of this is that then others can profit from picking up that cheap talent. We see a nice example of this in the obituary pages today:

As D J Freeman grew, it pioneered the promotion of women; in the 1980s when only 5 per cent of the partners in many City firms were women, in D J Freeman the figure was 40 per cent. The firm also introduced part-time partnerships and offered maternity leave.

This was both a matter of conviction, shaped by Freeman’s formidable wife Iris (née Alberge), a former child psychologist who retrained as an employment law solicitor so that she could work alongside her husband (and later wrote a biography of Lord Denning); but it was also a hard-headed recognition that a medium-sized firm needed to compete for talent, and women represented the largest single pool of untapped talent.

Steve Shirley (Dame Stephanie more formally) did this at about the same time by hiring married women, with children, programmers for her firm FI Group. And more recent research shows that the British football leagues were prone to this before the Bosman ruling in the 1990s.

What we find really interesting about this is the following: if such discrimination exists then it is possible for others to profit from it. Becker is pointing out that this will reduce said discrimination. But we can go one step further. In order to believe that such discrimination exists then you also need to believe that it is possible to profit from it.

So, how many do believe that in the modern UK it is possible to make, super, extra, profits by specifically looking to hire women and or ethnic minorities? If the answer is "no" then that's the same as stating the belief that there's no systematic discriomination, isn't it? If yes, then when are you hiring in order to profit from and then reduce said discrimination?

Economic Nonsense: 25. With free markets the poor are left behind

No. It is the poor who benefit most from free markets. The expensive new products that initially only the rich can afford become cheaper as time passes until they fall within what most people can afford. Colour televisions were initially a luxury product for rich people, but there was money to be made so more producers entered the market. The competition spurred firms to develop cheaper methods of production and improvements in quality. Colour TVs are now something that even poor people in rich countries are expected to own. Many consumer goods follow the same trajectory; most recently smartphones have done so. Far from being left behind, the poor are pulled along by the progress that initially caters for the rich.

Free markets offer a great variety, a variety that includes high fashion items for wealthy buyers, but also serviceable and affordable versions for those not so well off. A Bentley is a very fashionable, high quality car with four wheels that enables its owner to get around. A Vauxhall is less fashionable and less high quality, but it has four wheels and enables its owner to get around. The rich eat caviar, while the poor eat the equally nutritious but less fashionable cod roe. The princess and the movie star can wear the latest couturier designed Paris dress; others can await the High Street department store version inspired by it a few weeks later.

On a global scale, the world's poor have made huge gains because of free markets. Hundreds of millions have been lifted from subsistence and starvation because global free markets have enabled them to produce goods or services that sell to people in richer countries. They have not been left behind because globalization has admitted them into markets and allowed them to advance their living standards.

No, Robots aren't taking our jobs

The impact of mechanization on human employment has been a long-held concern. Long before robodoctors, drones and self-service checkouts the Luddites waged war with technology, smashing and burning the labour-saving machines they considered a threat to their livelihoods. Today, people like Tyler Cowen predict that the rise of intelligent machines will result in a society where the top 15% are fantastically successful and wealthy, but much of the traditional work of the lower and middle-classes is performed by robots and automation. Indeed, a much-cited 2013 study by the Oxford Martin Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology found that 47% of total US employment is at ‘high risk’ of computerization and could be automated within the next few decades. ‘Threatened’ sectors include transport, logistics and office administration, but surprisingly also the service sector, which is currently responsible for many of the new jobs created in developed economies.

Technological progress tends to have two differing effects on employment. At first there is displacement, as workers are substituted for new technology. However, efficiencies gained from automation often reduce prices, increasing real income and the demand for other goods. Companies will move into industries where productivity and demand is high and create new jobs, or use new technology to create new industries. Automation also frees up displaced workers to utilize their skills in other, potentially more fulfilling and creative ways.

Setting aside something like the singularity the economic impact of robots depends on whether they destroy more jobs than they create, and which section of society gains most from the opportunities they bring. At the moment, nobody really has a clue what future economic impact robots will have. Even a survey of nearly 2,000 experts in robotics and AI found that they were split down the middle in terms of techno-optimism (believing that robots will create more jobs than they replace) and techno-pessimism (that the rise of robots will inevitably adversely effect a significant number of blue and white collar workers).

Until now, there’s actually been very little empirical work done on the economic impact of the use of robots. However, a new paper — ‘Robots at Work' —from the Centre of Economic Performance at the LSE makes a welcome contribution to the field.

Using data from industries in 17 developed countries between 1993-2007, the report finds that ‘robot densification’ has no statistically significant effect on total hours worked over the period. This suggests that the use of robots has not (on net) resulted in less work opportunities for humans.

It has, however, had significant, and positive, effects elsewhere. The study found that the contribution robots make to economic growth is substantial, at 0.37 of GDP growth, and accounted for one-tenth of aggregate growth over the period. They also raised annual labour productivity by 0.36 points, comparable to steam technology’s boost to British labour productivity between 1850-1910. They also found that robot densification increased both total factor productivity and wages.

Industrial robots were used in under a third of the economy during the study period, and accounted for only around 2.25 percent of capital stock even within robot-using industries. The authors suggest that the likely contribution of robots to future growth is substantial, particularly when considering their potential impact in developing countries.

There is one note of warning, though — whilst the study found no overall impact of robot densification on hours worked, the use of robots did have a negative and close to significant impact on the hours worked by low-skilled workers, and, to a very small extent, those of middle-skilled workers. Presumably time will tell whether this is trend truly worthy of concern, and whether displaced workers are able to find alternative jobs elsewhere. For now, though, this study suggests that robots are tools which assist with and complement our jobs, as opposed to threaten them.

George Monbiot does rather misunderstand things

The latest bright idea from George Monbiot is that we must, in order to beat climate change, force people to leave fossil fuels in the ground. On the basis that it is necessary to attack supply as well as demand:

Imagine trying to bring slavery to an end not by stopping the transatlantic trade, but by seeking only to discourage people from buying slaves once they had arrived in the Americas.

It's an interesting example of his faulty logic. Because of course the transatlantic trade was at first banned in 1803 and then gradually extended to non-British ships and so on. But slavery lasted in the US until 1865 and into the late 1880s in Brazil, long after that supply was both legally and effectively banned. The solutions were variously more and less bloody but they were actually that people were dissuaded from purchasing slaves rather than that people were dissuaded from supplying them anew from Africa.

So it is, we're sorry to have to say, with fossil fuels and their associated emissions. We are not all victims of the evil capitalists (and, given that governments actually own the vast majority of fossil fuel reserves and resources, it's definitely not the capitalists to blame) who are forcing us to use such fuels. Rather, we the people rather like what we can do with such fuels: travel, heat our homes, heat our food and so on. It is the demand that needs to be changed (assuming that you want to consider climate change to be a problem), not the supply.

After all, banning the production of psychedelic drugs has proved so successful hasn't it? So too the supply of prostitution services where such is illegal. It really is worth recalling that while Say's Law (that supply creates its own demand) might not be entirely true the opposite, that demand calls forth supply is.

The answer to climate change, as above assuming that you think it is a problem and one that needs a solution (we do, even if not as immediate and cataclysmic as Monbiot does), is as it always has been. Either cap and trade or a carbon tax, plus research into non-CO2 emitting forms of energy production, in order to curb demand. Just as Bjorn Lomborg, the Stern Review, William Nordhaus, Richard Tol and everyone else who has actually looked at the economics of the problem has concluded.