Perhaps the 1% improve poor peoples' health?

A rather interesting little finding from over The Pond concerning the connection between inequality and the health of the population. Over here we've had Michael Marmot insisting for decades that health inequality is to be explained by economic inequality. And Wilkinson and Pickett have been shouting that they are not just connected by economic inequality is the direct cause of ill health for all. At which point we get the American study into health and inequality and we find something a little different:

A rather interesting little finding from over The Pond concerning the connection between inequality and the health of the population. Over here we've had Michael Marmot insisting for decades that health inequality is to be explained by economic inequality. And Wilkinson and Pickett have been shouting that they are not just connected but economic inequality is the direct cause of ill health for all. At which point we get the American study into health and inequality and we find something a little different:

Income inequality (as measured by the Gini index) was not statistically correlated to life expectancy, but it was in a positive direction (greater inequality correlated with higher life expectancy) and approached significance.

It is of course wrong to take a result which is not statistically significant and then claim that this is a significant result. Except, again of course, unless you make the correct claim about what is significant.

If it were true that economic inequality does indeed lead to the population keeling over like mayflies then we would expect to see it as a significant result of such a study. For they really were looking at the lifespans of rich and poor in the various different population centres of the US and seeing whether the local inequality affected those relative lengths of lifespans. We can't claim, not with any power at least, that inequality increases those poor lifespans for that result is not significant. But we can claim that the opposite, that inequality shortens those lifespans, is somewhere between not proven and wrong.

If it were true it should show up in this evidence. It doesn't: not proof perfect but highly indicative. Which is an interesting finding, no?

The big causes of variance in lifespans were the ones we might think of: smoking, obesity and exercise. Economic inequality just doesn't seem to be enough of a cause to create a statistically significant effect.

Politicians complaining about how politics works

The current complaint from these politicians seems to be that they don't like the way politics works:

The current complaint from these politicians seems to be that they don't like the way politics works:

The three councils that have suffered the least from cuts in George Osborne’s controversial budget are represented by Tory cabinet ministers, a new analysis shows.

Wokingham, Surrey, and Windsor and Maidenhead have all seen the lowest cuts to their budgets despite being the three least deprived areas in the country. The areas cover the constituencies of five cabinet ministers: Theresa May, Jeremy Hunt, Chris Grayling, Philip Hammond and Michael Gove.

That Tory cabinet members sit for leafy and well off constituencies is not really one of those things we can get surprised about. We rather think it's the nature of the beast to be frank.

But the complaint goes further:

Jon Trickett, shadow secretary of state for communities and local government, said the analysis confirmed that Osborne’s commitment to austerity was ideological. “It is disgraceful that the most deprived areas in our country are bearing the brunt of the Tory government’s ideological cuts to local services when the least deprived areas, which happen to be home to five of David Cameron’s top ministers, are seeing the least amount of cuts,” he said.

“To add insult to injury, these deprived areas did not receive a penny in the £300m transitional grant whereas the three least deprived received over £33m. Most people would come to the conclusion that the Tories are ruling in their own interest.”

Well, yes, we suppose they are. And we suppose that's why people voted for Tories really: so that the Tories would do things in favour of the people who voted Tory. We are actually pretty sure that's the way this democracy thing is supposed to work. People vote for what they think is in their best interest and whoever is elected then goes off and does that, yes?

However, it's not quite necessary to revel in such cynicism to be able to explain what is really happening here. Way back in the Blair years, under the Brown Terror, there was significant redistribution of local government resources from those richer, leafier suburbs to the poorer and more likely to be Labour run areas of the country. The Coalition was rather an interregnum and now under a Tory government that redistribution is being undone.

Maybe it's a good thing that it is, maybe it's not a good thing. But that is what is happening: simply the unwinding of a policy of a government after said government lost an election. Which is, at least we think it is, the way this democracy thing is supposed to work, isn't it?

This morning's Guardian produces a bit of a giggle

That's our first reaction, at least, to this story that a Welsh billionaire is willing to invest some of his own money in a rescue of the Port Talbot steel assets. The giggle coming from, no, not the idea that there is a Welsh billionaire, the thought that, well, yes, that's what we rather expect from people when they buy something. They use their money to buy the thing that they're buying. Seems a reasonable and logical idea to us but it's obviously caught The Guardian by surprise:

That's our first reaction, at least, to this story that a Welsh billionaire is willing to invest some of his own money in a rescue of the Port Talbot steel assets. The giggle coming from, no, not the idea that there is a Welsh billionaire, the thought that, well, yes, that's what we rather expect from people when they buy something. They use their money to buy the thing that they're buying. Seems a reasonable and logical idea to us but it's obviously caught The Guardian by surprise:

Tata Steel: Welsh billionaire could plough own money into UK buyout

We think that "own money!" is really rather cute in fact.

Welsh billionaire Sir Terry Matthews has said he could be willing to put his own money behind a management buyout of Tata Steel’s UK business and the Port Talbot steelworks.

Matthews said he is “feeling really good” about the prospects of a rescue deal for the steel business, which could save thousands of jobs in the UK.

Matthews, who made his fortune in technology and telecoms, is part of a consortium of public and private sector figures from south Wales supporting a management buyout.

And that's where it all becomes a little less amusing. Because of course that's not really what is being said at all. Instead the argument is that if government (that's you and me and our pocketbooks as taxpayers) were to, say, pick up the pensions bill, the environmental costs, chip in a bit.....oooh, let's say 25% of the cost.....towards upgrading the facilities, then maybe private sector actors will chip in a little of their cash as well.

We can't help but suspect that the taxpayer money would have to be first in the queue to be spent while that private sector money would be the first to be paid out again.

We're not against government doing things for the public good: we just tend to argue about what that public good is and how to define it. And structuring business deals which look as if they're privatise the profits and socialise the losses just doesn't qualify as something good for the public to us. However surprised The Guardian gets at people being willing to spend their own money.

The effects of Osborne's new national living wage

St Joseph's Hospice is in Liverpool, where it cares for the terminally ill in a manner that the National Health Service simply never can manage. They have sent the following around to their supporters:

Charity shop staff who work for Jospice face the prospect of losing their job due to rises in the minimum wage…

There are currently eight retail managers working across these shops but it is proposed that this number be reduced to five.

The decision has been blamed on the government’s new National Living Wage, which rose to £7.50 an hour for over 25s as at the start of April and is expected to rise to £9 by 2020.

A spokesperson for Jospicesaid: ‘We have informed our eight retail managers that we propose to implement a new retail team structure. Due to ever rising costs and the introduction of the National Living Wage we are unable to continue with the existing staff structure within our retail team….

As a charity we have to raise half our income through fundraising in our local communities and so we have to be as efficient as possible.

We'd just like to say well done Chancellor, well done.

Prosperity Mr President? The EU is the slowest-growing trading bloc in the world

President Obama says the UK needs to stay in the EU to promote ‘peace, prosperity and democracy’. Sadly, the EU does not promote any of these.

Peace in Europe is promoted by NATO. Look at the Balkans war. Though appalling genocide was going on under the noses of EU ‘peacekeepers’, the EU was unable to bring the conflict to an end. It was only when NATO – led in large part by the UK – stepped in that the carnage was stopped.

And take Ukraine. It wanted closer links with the EU, but the EU’s ‘all or nothing’ policy made Putin fearful that this buffer state would turn into a Western enemy. The EU could do nothing to resist the occupation that followed.

Prosperity? The EU is the slowest-growing trading bloc in the world. Partly that is because of its sclerotic common currency, the euro – a political project that was pursued in the face of economic commonsense.

Democracy? Power in the EU centres on the Commission, a group of appointed, not elected, politicians and officials. The public do not directly elect the national politicians who sit on the Council of Ministers – nor, for that matter, the panels of finance and foreign-policy ministers. And the vast majority of people in the UK have no idea at all who their Member of the European Parliament is. Not that the Parliament has any power to initiate legislation anyway. Our own legislation, and our Supreme Court, are overridden by EU institutions.

For such a powerful nation, America is remarkably naive about foreign policy. The Administration seems to think that the EU is a kind of NAFTA, a loose free-trade agreement. In fact it is a political union – and one that no American would, on closer inspection, ever wish on itself or its friends.

Something of a blow to Piketty's thesis

The more research that gets done into the details of Thomas Piketty's thesis (essentially, wealth concentration will leave us all as serfs again) the more there seem to be great gaping holes in it. For example, a central piece of the logic is that wealth will pile up, this will be inherited, and that wealth inequality will thus get worse over the generations. We're not convinced that such a bourgeois world would be a bad one but that thesis does depend upon the idea that inheritance concentrates wealth.

Which, apparently, it doesn't:

Studies analysing the link between inheritance and wealth inequality have used different methods and data sources, ranging from simulated distributions to individual observations in surveys or data on wealth from tax records (e.g. Davies 1982, Wolff 2002, 2015, Boserup et al. 2016). Consensus has not yet been reached over the exact relationship. However, a recurrent result, which Wolff (2002) was the first to find, is that, perhaps surprisingly, inheritances tend to decrease wealth inequality.

Note that this isn't a new finding: it's just that Piketty assumed the opposite.

In a recent study (Elinder et al. 2016) we examine how inheritances affect wealth inequality using a new population-wide register database. The database contains detailed accounts on wealth and inheritances (including zeros) for all family and non-family heirs of every deceased person in Sweden during several years in the early 2000s. These rich data enable us to estimate the causal effect of inheritances on the distribution of wealth and, importantly, to also uncover the mechanisms underlying this effect. We are also able to study the distributional consequences of inheritance taxation and the effect of inheritances on wealth mobility.

Our main results establish what previous studies have pointed to, namely that inheritances decrease the inequality of wealth.

The Gini coefficient decreases by 6%, a relatively large effect which is roughly in line with the wealth compression following the burst of the dotcom bubble in 2000 when stocks in internet companies, held mostly by the wealthy, lost their value.1

We also find that inheritances increase the absolute dispersion of wealth among heirs, measured as the difference in wealth between the heirs in the 25th and 75th percentiles of the distribution.

Isn't that fascinating? And more, the taxation of inheritances itself increases wealth inequality.

We observe the exact amount of inheritance taxes paid by each heir (some pay nothing), and when we examine how the tax payments affect the wealth distribution we find that the tax has a dis-equalising effect. That is, all else equal, the tax by itself tends to increase wealth inequality.

Of course, dependent upon what the money raised is spent upon the act of spending can reduce inequality again. But if inequality is the point and purpose of inheritance tax, which for many it is, there seems little point in increasing inequality by said taxing only to use the revenues to undo the effects just caused.

Our own longer term view has been that inheritance tax hasn't worked. The truly rich don't pay it, using trusts and lifetime gifts and so on. It's the less than plutocratic but still successful that do pay it. We've noted that old folk wisdom, clogs to clogs in three generations, and think that it has good predictive power. Even the inheritance of the grandest fortune cannot survive an inheritor truly determined to waste it and eventually, given the way genetics seems to work, one does always turn up to do such.

This might not draw nods of approval from those who would plan society but we've at least an urge to let people inherit as they may and leave the occasional existence of spendthrifts to deal with wealth concentration. There's very, very, few (in fact, other than those very few aristocratic families who held substantial urban land and kept it, we're not sure there are any) fortunes that have survived more than three generations.

The sands of time seem to deal well enough with this problem, why plan for it?

Jared Bernstein is wrong about supply side economics

Jared Bernstein, former chief economist to US Vice President Joe Biden, has an op-ed on the Washington Post website purporting to refute supply-side economics, the school of thought that believes that lower taxes (and better taxes) means higher economic output overall. He plots a few charts that show that the top marginal tax rates of the USA in a year is uncorrelated (or even positively correlated in some cases) with investment growth, employment growth, productivity growth, growth in GDP/capita, family income growth, and tax revenue growth.

He makes astonishingly strong claims on the back of this data, but he is deeply confused and mistaken about the evidence he'd need to make the case he wants to make. What's more, there is a lot of rigorous empirical evidence against his argument. This evidence suggests that lower taxes do lead to more output being created; although at the current rates, tax cuts are unlikely to create so much more output that they 'pay for themselves' like some previous cuts.

Before explaining why the bulk of the evidence goes against Bernstein, we should ask why an economic model of the economy predicts that lower taxes means higher output, employment, productivity and so on. Nearly all taxes distort incentives—that is reduce the incentive to do productive and socially beneficial things. Taxes on consumption and labour income make leisure cheaper compared to market goods, so people take more leisure than they otherwise would. They also make career paths with higher hours, more delayed consumption, less pleasant conditions, and less social prestige, less attractive compared to more pleasant but less well-paid careers. Taxes on transactions gum up efficient allocation, reducing the incentive for older people to downsize in the housing market, and reducing the incentive for traders to buy when they think prices are away from reality. Taxes on investment returns reduce saving and investment, and increase current consumption, so there are less tools, training, communication and less efficient organisation in the future.

Bernstein's argument assumes that people ignore these incentives—but economists believe there is strong evidence both anecdotally and in the empirical academic literature that people respond to incentives, even when it comes to very serious personal decisions. For example, when a US state bans affirmative action policies, multiracial Americans are 30% less likely to self-identify as their minority ethnicity. American divorcees who had been married for 10-years are eligible for spousal Social Security benefits—divorces rise 20% around the 10-year mark.

A swathe of papers show that financial incentives drive retirement decisions—when benefits are more generous, people retire earlier. Immigrants will typically not leave their country unless their expected lifetime earnings are at least $500,000 more in their new home. They often return to their native country if their earnings expecations fall—as did a third of Polish immigrants in the UK. And travellers in Sierra Leone even pick between different modes of transport between Freetown and the airport—ferry, helicopter, hovercraft, and water taxi—based on a trade-off between mortality risk and cost. It would be very surprising then if people weren't partly affected by financial incentives when interacting in the market sphere. In fact, there is a consensus among economists that taxes have very large costs in terms of distorted activity.

Aren't Bernstein's graphs evidence against this? No. When you test an economic theory, you need to try and control for "confounders"—factors that you haven't measured that could affect your results. If you find a strong correlation between breastfeeding and child IQ, but you haven't controlled for parental IQ, then you don't know whether the breastfeeding itself is driving higher child IQ, or if those children had high IQ mothers, and would likely have had high IQs whether or not they'd been breastfed.

In the same way, the top marginal income tax rate is not the only thing going on in a year—for one thing, there are lots of other taxes in the economy, all of which could be high when income taxes are low, and vice versa. We don't even know how many people are paying this top rate—this will change between years. Supply-side economists predict that lowering the overall tax burden will improve economic outcomes, not that the top rate of one particular tax is the key issue. But supply-side economists also think that there are other very important factors. For example, the entire world grew very quickly in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, as we rebuilt after the second world war, trade links expanded, and new technologies filtered through economies. The US also had high top tax rates then—but with lower rates, the US might have grown even faster.

So one more rigorous way academic economists test theories about the macroeconomic effects of tax is by looking at the economy before and after tax changes. For example, James Cloyne's paper "Discretionary Tax Changes and the Macroeconomy: New Narrative Evidence from the United Kingdom" in the top economics journal, the American Economic Review finds that "a 1 percent cut in taxes increases GDP by 0.6 percent on impact and 2.5 percent over three years". A 2012 literature review from the Tax Foundation found only three of 26 empirical studies where higher taxes did not mean lower growth.

It would be very surprising if Jared Bernstein was right that taxes do not affect growth and other economic variables, because our simplest, most intuitively appealing, most empirically verified models predict large effects when incentives are distorted. But Jared Bernstein is wrong: his own tests are extremely simplistic, and do not attempt to account for confounding factors. Once you do, the evidence is clear: higher taxes mean lower growth. Of course, there are still reasons why we might want to tax—but it's a tough trade-off: the more government programmes we fund, the poorer we are on average.

Why Divorce Should Be Easier

The divorce rate is often held up as proof of social breakdown. Asides from the collapse of the nuclear family and bringing misery on former spouses and their children, it represents the triumph of selfish individualism over responsibility and self-sacrifice. Divorce is often painful, especially where children are involved. However, if people are definitively committed to divorce, staying married could be even worse.

Still, the fact that forty percent of marriages now end in divorce can be taken as proof that the process is too easy. But is it? England and Wales do not have ‘no faults divorce’. Unless you separate for two years and agree to end the marriage (or five without agreement), some form of proven fault on one side is necessary, whether this is adultery, desertion, or unreasonable behaviour.

In some cases this is easy to establish and it is fair to blame one party. Proving unreasonable behaviour is not especially hard, given the wide and vague definition. As far as the actual divorce goes, it is not difficult, not withstanding the recently increased court fee, presumably intended as a disincentive.

The current rules become problematic when dividing financial assets and reaching agreement about childcare and access. Given the usual need for fault on the part of one party, any acrimony is exacerbated and the person taking the blame is at an automatic disadvantage. Where unreasonable behaviour is emotional or physical abuse, this is fair.

However, as one party can simply concede their ‘unreasonable behaviour’ to speed up the process, it can create unnecessary unfairness and resentment. In other cases, where both parties have been at fault this can incentivise a race to pin blame first and most squarely.

A positive step would be to allow a marriage to be dissolved unilaterally without the need for justification, so long as there are no children under eighteen. Even in child cases, a less protracted and more harmonious process can only be positive, and it is unlikely that children benefit from having two parents living together who openly despise each other. The separation period could be reduced to one year with agreement and two without, given that by this stage the family has already broken down.

Where there are no underage children, there is no reason for obstacles to divorce. The idea that all committed, meaningful relationships have to last forever is rather odd. For many people, it works, and is wonderful. But, others may find a marriage attractive at one stage of their life, and, without fault, simply not feel this way later.

In general, a high churn rate is a healthy indicator. People change service providers and employer regularly. They are happy with one for a period, but due to their priorities or situation, or the other party’s terms, changing they are free to exit and choose something they prefer under new conditions. There is no reason marriages should not work more like this.

There's something that really annoys us about certain working hours campaigners

Many note the prediction by Keynes that working hours today would, or could, be much shorter than they were when he was writing. Some then go on to insist that we should change how we organise things so that they are. It's that latter that so annoys us, for a philosophical reason firstly and then for a technical one.

Many note the prediction by Keynes that working hours today would, or could, be much shorter than they were when he was writing. Some then go on to insist that we should change how we organise things so that they are. It's that latter that so annoys us, for a philosophical reason firstly and then for a technical one.

Had you asked John Maynard Keynes what the biggest challenge of the 21st century would be, he wouldn’t have had to think twice.

Leisure. In fact, Keynes anticipated that, barring “disastrous mistakes” by policymakers (austerity during an economic crisis, for instance), the western standard of living would multiply to at least four times that of 1930 within a century. By his calculations, in 2030 we’d be working just 15 hours a week.

In 2000, countries such as the UK and the US were already five times as wealthy as in 1930. Yet as we hurtle through the first decades of the 21st century, our biggest challenges are not too much leisure and boredom, but stress and uncertainty.

What does working less actually solve, I was asked recently. I’d rather turn the question around: is there anything that working less does not solve?

That philosophic objection first. For there is one thing that working less does not solve: what people want to do. Our job in the organisation of society is not to impose some order upon it, not to insist upon some right way of living which must be followed. It is, because we are liberals, to order matters so that every member of that society can live their lives, right up to the boundaries of where their doing so impinges upon the similar rights of others, as they wish. We should therefore be observing what people actually do in order to work out what they want to do.

Keynes was indeed correct that economic growth would make us all that much richer. But what we've found out over that period of time is that our hunger for more tchotchke is rather larger than Keynes thought it was. Ho hum, oh dear, we're still though trying to accommodate the wishes of the people, not impose our own visions upon them. Thus we cannot observe that people prefer to work more than Keynes said they might and then insist that they should work the shorter hours that Keynes was wrong about.

Which brings us to the technical matter:

The central issue is achieving a more equitable distribution of work. Not until men do their fair share of cooking, cleaning and other domestic labour will women be free to fully participate in the broader economy.

Even a brief look at the ONS statistics will show that labour is in fact pretty equally spread across gender lines these days. Adding household and market work together men and women do pretty similar amounts. As, in fact, they did back in Keynes' day. For the obvious reason that the total workload is going to be pretty evenly balanced in something as intimate as a marriage to run a household. What gets us very hot under the collar indeed is that near everyone opining on this matter misses the most important change over those decades. Household labour has declined as much as if not more than Keynes predicted.

This might be a little over cooking the numbers but we have seen claims that a household in 1930 required 60 hours of work a week to keep running. Just washing the clothes was in itself a full day's labour on its own. Today that number is perhaps more like 15 hours. For the household for the week, not the clothes washing.

That is, we have reduced our working hours as Keynes predicted. It's just that it was that traditionally female labour in the household that was reduced by that amount.

Another way to put this is that it's simply crazy to go around shouting that everyone should do less market work and help out more at home. We've a century of experience on this in many different countries. Near everyone wants to do it the other way around: kill off as much of that domestic work as possible with technology and go out to do the interesting market work to pay for it. And since we are liberals that's what we should be aiding them in achieving, their goal, right?

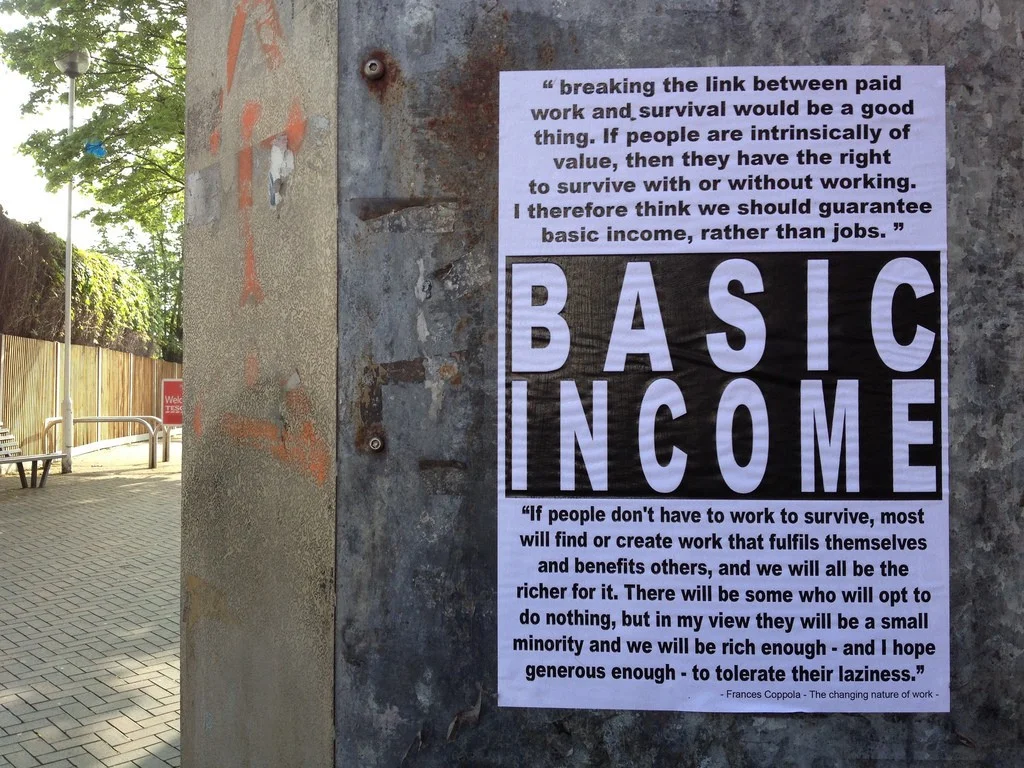

A neoliberal case for a basic income, or something like it

If I’d never encountered the idea of a basic income before reading Laurie Penny’s recent article on it, I’d come away hating it. For Penny, it’s about replacing capitalism with something better. For me, it’s about improving the capitalism we already have.

Penny thinks that the idea is ‘blasphemy to conventional, liberal, “free-market” economists’. It’s not: we here at the Adam Smith Institute have proposed something along these lines for a couple of years, and Milton Friedman proposed a similar Negative Income Tax way back in 1962.

I suspect her utopianism will be off-putting to most people. She asks, “What would society look like if that sort of freedom were available to everyone: if advances in technology and productivity could benefit not only the very rich, but all of us?”, but most people actually benefit quite a lot from advances in technology and productivity already. 66% of British adults own a smartphone (also known as “the sum of all human knowledge, in your pocket”); wages are up by over 62% in real terms since 1986; and that doesn’t even mention the enormous global reduction in poverty in the age of neoliberalism.

Penny says that “unconditional basic income is a proposal that requires us to rethink the economic and ethical framework of neoliberal capitalism that has governed our lives for generations”, and for a basic income to work, “all that it requires is that we trust one another.” Er, thanks, but no thanks.

I’m a capitalist, neoliberal advocate of a basic income, or something like it. I don’t think it’s perfect, I don’t think it will solve every problem. I just think it would be an improvement, for three main reasons:

- It addresses in-work poverty well.

- It reduces complexity in the welfare system.

- It facilitates other reforms that would raise overall living standards.

1. It addresses in-work poverty. Our existing welfare system is designed for a world where finding a job would be enough to give most people a tolerable standard of living. But in-work poverty is an increasing problem, particularly as good jobs for poorly educated workers become unviable, and the welfare system that we have at the moment isn’t well built for that.

This is where the robots come in. I’ve heard it said that automation of the economy is a lot like going to Australia – it’s great when you get there, but it can be a difficult journey. As robots replace them we probably will think of new things for people who used to work in law firms, factories, call centres and hospitals to do, but it might take some time.

Automation and globalization will both raise overall living standards, and in the case of globalization it will make very poor people in the developing world a lot better off, but we cannot guarantee that the jobs people get instead will be as good as their old ones. Working tax credits already begin to tackle this issue, but a basic income would reorient the whole system towards helping people who don’t have enough money, irrespective of why that is.

2. It reduces complexity in the welfare system. Our existing welfare system has built up a large amount of unnecessary complexity that could be streamlined. Like much public policy welfare is ‘path dependent’ – no two country’s welfare systems are the same, even if their welfare problems are. Much of the complexity in the welfare system has built up over time and exists only because of loss aversion: once we’ve started giving winter fuel payments to pensioners it’s quite difficult to stop.

Many but not all of these benefits are fundamentally about giving money to people who do not have enough of it. Housing benefit, the pension credit, jobseeker’s allowance, income support and tax credits all do this. But the case for a basic income does not need to stand or fall on whether we could replace all benefits with it. Some people inherently need more money to live decent lives, like the disabled, infirm and elderly. Reducing complexity is valuable but not the only, or indeed the main, appeal of the basic income.

3. It facilitates other reforms that would raise overall living standards. Many other policies that would increase total wealth are not very progressive, distributionally speaking. Tax systems are better when they do not tax things like investment and when they don’t exempt certain things from consumption taxes (like VAT), but doing these things ends up making lower earners pay more tax than we would like. One objection to immigration is that even though it makes natives richer overall, it has a small, temporary negative hit to the poorest natives. An easy way to correct that would be to redistribute the overall wealth gain to those poor natives so that they too are made better off in the short run as well as the long run.

Some pernicious government policies are ones that attempt ‘off balance-sheet’ redistribution. The minimum wage, for example, is hoped to be a redistribution from consumers and shareholders to low-paid workers – profits fall and prices rise to pay for their new, higher wages. The problems with it are that it has other unintended consequences, like causing unemployment for some workers, and that higher prices may hurt the poor as well. There’s no free lunch here – it would be more effective to tax people and then redistribute it directly to poorer workers. A basic income could replace policies like this.

I’ve used the words ‘basic income’ and ‘negative income tax’ interchangeably for a long time, because at their core they are both pretty much the same thing. The basic income is certainly better known than the negative income tax. But the problem with it is that for equal levels of basic income and negative income tax, a basic income would require large headline tax hikes.

We couldn’t just take all existing welfare spending and divide by the population – that would mean taking loads of money from people currently on welfare and giving it to people on higher incomes. We’d need to set the level quite high to avoid this outcome, and then ‘claw it back’ in the form of higher taxes.

Since people are getting the money back we wouldn’t actually be taxing anyone any more, but there would probably be large deadweight losses to reckon with, as there usually are with higher marginal taxes. Even if we could reckon with them, it would be a difficult proposition politically. (Perhaps it would work if we did a huge one, as Charles Murray has proposed, that replaced most of the state's activites altogether with cash payments - that means scrapping the NHS and education systems and giving people the money instead.)

So, even if it is a simpler concept to explain, the ‘basic income’ might be a hard sell. The very similar Negative Income Tax, which tapers away as the recipient’s earnings rise, could be a simpler solution that avoids utopian pitfalls like the ones Laurie Penny has stumbled over.