Two particularly stupid views of trade in one morning

It's rare to be treated to two pieces of stupidity about trade on the same day but here we are, the event has happened. And sadly the people in error are people who do have at least some modicum of power over our lives.

The error being made is to be mercantilist. To think that it is the exports which are the purpose of trade, the exports which make us rich. This is, as we all know, precisely the view which Adam Smith railed against that 240 years ago and Adam Smith was right. Both in what he said and in said railing. For it is, of course, the imports which make us rich, the reason we trade is to gain access to those imports.

Here is Liam Fox:

“If you want to share in the prosperity of our country, you have a duty to contribute to the prosperity of our country,” he is reported as saying, hinting that companies that do not take advantage of new export opportunities could face sanctions.

Clearly thinking that it is exporting which makes Britain rich:

He added: “We’ve got to change the culture in our country. People have got to stop thinking about exporting as an opportunity and start thinking about it as a duty — companies who could be contributing to our national prosperity but choose not to because it might be too difficult or too time-consuming or because they can’t play golf on a Friday afternoon.”

Again, exporting being equated with increasing the wealth of the nation. From the other side of the Channel we have M. Macron who is an odds on runner for the French Presidency:

British-based financial institutions must be prevented post-Brexit from selling their services in the eurozone, Emmanuel Macron, the likely progressive left candidate for the French presidency has told the Guardian.

This is the same mistake. It is to think that the British companies doing the exporting are the beneficiaries of such exports. When nothing is further from the truth. Those who benefit are the consumers who get to enjoy the imports. for that is why we do this trade thing - in order to gain access to those things which Johnny Foreigner does better or cheaper than we do. And that's the only reason we do trade too.

It gets worse:

But Macron insisted:

“The financial passport is part of full access to the EU market and a precondition for that is the contribution to the EU budget. That has been the case in Norway and in Switzerland. That is clear.” The proposal would be rejected outright by British Eurosceptics.

The insistence is that being able to sell to people is a privilege, one that a government must pay for so that businesses may do so. But this is incorrect - the benefit is to those who may buy the imports.

By not grasping the most basic point about trade M. Macron is threatening to hold the people of the European Union hostage unless some gelt is paid to the Brussels bureaucracy. He really is shouting that he'll make Europeans poorer unless the Brits give him some money. Such is the lunacy one is driven to by not understanding the basics of trade.

It has been 240 years now since the Wealth of Nations was published. We'd really rather hoped that people had grasped the point by now.

Re-dressing old wounds: The unintended consequences of NHS prescription regulations

The current system for exempting certain patients from paying for their NHS prescriptions is discriminatory, unjust and unfit for purpose. The high cost of prescription medication deters many patients from engaging consistently with treatment, increasing their risk of adverse outcomes such as strokes and heart attacks.

When Bevan introduced the NHS in 1948, his intentions were clear and noble: nobody in this country should suffer from a treatable illness or ameliorable impairment because they were too poor to afford care.

The current system for exempting certain patients from paying for their NHS prescriptions is discriminatory, unjust and unfit for purpose. The high cost of prescription medication deters many patients from engaging consistently with treatment, increasing their risk of adverse outcomes such as strokes and heart attacks.

When Bevan introduced the NHS in 1948, his intentions were clear and honourable: nobody in this country should suffer from a treatable illness or ameliorable impairment because they were too poor to afford care.

Unfortunately his advisors had under-estimated the scale of demand for health services. From every corner of the country, people emerged in droves requesting glasses, false teeth, and wondering whether they could discard their antique trusses if they had their hernias repaired surgically.

On 1st June 1952, after four years of dismayed contemplation of the rising cost of the NHS, a prescription charge of one shilling was imposed, and a charge of one pound for dental treatment.

In 1965 prescription charges were removed again, but this was again a short-lived interval and in 1968 they were reintroduced. The only difference was this time, they were not for everyone. A list of exemptions was drawn up, based on the state of medical art in 1968, and this list has remained largely unchanged since then. In 2009 there was one major addition, to exempt people suffering from cancer, but otherwise the list has been embalmed.

As is often the case with overly complex regulations, unintended consequences arise. The aim of the original list of exemptions was to ensure that people whose lives depended on regular medication should never be unable to afford that medication.

Exemptions were granted to:

- People with epilepsy needing continuous medication

- Myasthenia gravis, a neurological condition which can lead to profound disability and death

- Certain hormone deficiencies (but only those which were recognised in 1968 and were expensive to treat in 1968)

- Anyone who had a fistula (a hole causing body fluids to leak from the urinary system or digestive system onto the skin surface), if that hole was permanent.

In 2009 cancer patients were included, not only for their initial phase of treatment, but potentially on a permanent basis. They are exempt from paying for prescriptions as long as they are having treatment for cancer or for the side-effects of treatment. So, if they develop a coin-sized patch of dry skin where they had radiotherapy and need an emollient cream for that, then they qualify for all their prescriptions to be free forever. Moreover, like all patients who are exempt for one reason, all other prescriptions for unrelated problems are covered by the NHS.

As a doctor, scenarios like the following are quite typical. This morning I saw Mr A, who has high blood pressure and asthma. His medical treatment is essential. Without it he will be unable to work and will be at a much higher risk of strokes, heart attacks and death from asphyxiation.

He is not exempt from prescription charges and must either pay £8.40 for each of the six medications he has to take; or he can pay £109 for an annual season ticket. He is open about his reluctance to use medication regularly because despite his reasonably high income, he has a dependent family and doesn’t feel able to spend the money on medicine for conditions which do not immediately incapacitate him. High blood pressure at this level does not produce any symptoms at all until the stroke or heart attack or kidney failure occurs.

Then I saw Mr B, who also has high blood pressure and asthma, but is also severely obese and has over-taxed his pancreas so he has to take tablets to keep his blood sugar down. His pancreas does produce insulin, but not enough to cope with what he eats, and the fat around his abdomen produces substances which impede the action of his natural insulin. A few years ago he managed to stick to a diet and his blood sugar was normal without medication, but then he resumed over-eating and it went out of control again. He is classified as a type two diabetic, and as a diabetic he can claim all his prescriptions free. All diabetic people are exempt, except those who change their lifestyle and diet in order to control their blood sugar without medication. Over-eating saves Mr B £109 per annum, and he gets other benefits such as free eye checks.

Mr B is not exceptional. Studies have indicated that the majority of people with type two diabetes mellitus could cure their diabetes by restricting food intake.

This injustice has not passed unremarked. In 2008, Professor Ian Gilmore was asked to review the current arrangements with a view to extending exemption to everyone with a chronic medical condition. His report suggests that the current list was illogical and unfair, but he was worried about the cost implications of levelling the playing field, observing that the NHS would lose revenue of £500 million per annum if prescriptions for chronic conditions were dispensed free of charge. Professor Gilmore suggested phasing in the new, less discriminatory system, and used phrases such as “as soon as possible” – but seven years later, no progress has been made.

Professor Gilmore is appropriately cautious. An Ipsos Mori poll from 2008 indicates that in the course of one year, 800,000 UK residents did not collect a prescription because of the cost. One billion NHS prescriptions are dispensed annually, so there would be approximately an 8% increase in the number of prescriptions dispensed if cost were no longer a barrier.

The NHS could be at risk of a successful class action by one of the minorities who suffer in particular from this system. High blood pressure is much more common in certain ethnic groups; for example, about one in three US black people need medication for it, compared to one in four white people. Alternatively a patient group action might ensue, perhaps by people who have asthma and who need to pay for medication throughout their adult life while they are making an active contribution to the NHS, until they reach sixty and qualify for free medication.

The NHS is an expensive luxury, but having seen the consequences of living without a well-organised public health care system, nobody would want to make it unsustainable. The cost of prescription medication is a significant element, so we need a solution which will be more equitable.

If we were to abolish exemptions from prescription charges, the NHS would gain revenue. If we also abolished pre-payment certificates, the revenue would be a significant contribution to the cost of the service. There would be additional savings because the £8.40 item charge does not cover the cost of paying for the medication and the dispensing service. In other words, every prescription not dispensed represents a greater saving than the cost of the drugs. People would no longer collect medications they do not intend to use, whereas when I do home visits and ask about medication, I am frequently introduced to a private pharmacy containing collections of unopened boxes, collected over the years “just in case”.

It would not be fair, of course, that people with chronic conditions would need to pay for medication. Indeed, it was never their choice to suffer those conditions in the first place. However, we are deluding ourselves if we believe we can make life entirely fair. People would still be protected from much of the cost of their treatment, if there continued to be a flat rate charge per item.

Finally, people should be free to prioritise the demands on their budgets. Long-term medications are generally prescribed in quantities to cover a three-month period, so if there were a £10 charge per item, that would equate to less than £1 per week. Some people choose to prioritise their health needs; they manage their diets; take regular exercise; avoid smoking and drinking to excess – and take regular medication as and when required. Others place less of an emphasis on health maintenance, and that is a lifestyle choice which they should be free to make.

Why Europeans really do need American healthcare

Psychiatrist and blogger Scott Alexander has been on a tear lately about the price of pharmaceuticals in America, in particular the EpiPen, a common device used to treat people who have had severe allergic reactions. The EpiPen’s price has been hiked by about 400% since 2007, which left-wing website Vox blames America’s lack of price controls for but Scott blames on America’s cronyish regulation:

Let me ask Vox a question: when was the last time that America’s chair industry hiked the price of chairs 400% and suddenly nobody in the country could afford to sit down? When was the last time that the mug industry decided to charge $300 per cup, and everyone had to drink coffee straight from the pot or face bankruptcy? When was the last time greedy shoe executives forced most Americans to go barefoot? And why do you think that is?

It’s a fascinating piece and worth reading in full.

But what I’m really interested in is a part of his follow-up piece where he looks at rates of pharmaceutical innovation in the US, compared to countries with price controls:

1. Golec & Vernon (2006) say that as a result of European drug price regulation, “EU consumers enjoyed much lower pharmaceutical price inflation, however, at a cost of 46 fewer new medicines introduced by EU firms [over a 19 year period].”

2. Eger and Mahlich (2014) find that among pharmaceutical companies, “a higher presence in Europe is associated with lower R&D investments. The results can be interpreted as further evidence of the deteriorating effect of regulation on firm’s incentives to invest in R&D.”

[…]

So by my count, there are eight-and-a-half studies concluding that price regulation would hurt new drug innovation, and one-half of a study concluding that it wouldn’t. I’ve tried to eliminate all the studies sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry from this list, but I might have missed some.

Scott also cites an impressive-looking RAND Corporation paper which tries to project the consequences of government price-caps in healthcare.

In the short-term, things get better – drugs are cheaper. Great! But in the longer-term, things get worse. Much worse. Innovation declines and life expectancies fall in both the US and Europe.

Which makes me think that, as bad as the US system is in many ways, there’s a very important silver lining. All that money and intellectual property protection create much, much bigger incentives for healthcare innovation in the US than in Europe.

And that allows those of us in price-controlled countries to get something like the best of both worlds: cheap(er) drugs, but lots of research for new drugs, funded by our less fortunate friends in the United States. In a very important sense, it looks as if we’re free riding on American healthcare spending.

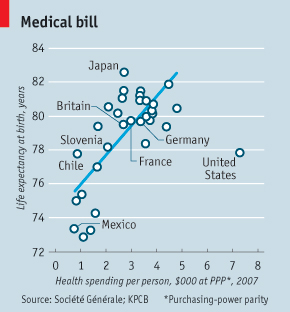

None of which is to say that the US system isn’t a dog’s dinner. Read Scott’s posts to get a flavour of that. But it does make smug posts and charts like the one above, which laugh at the nutty Americans and their wild, wasteful overspending, look quite silly. Without Americans spending all that money on healthcare, those of us living in price-controlled European systems would be living shorter lives, too.

The dirty little secret about GDP

An interesting point made in The Times about GDP:

For even GDP — the greatest, most definitive statistic of all — is really just a survey too. Forms are posted out to a selection of companies where they are filled in and sent or faxed back (“Informed estimates are sufficient for our needs”, says the bumf). Those figures go into a model and soon enough they become GDP. The size of Britain’s economy, the question of whether we are in or out of recession, the fate of governments — ultimately it all hangs on a questionnaire.

Well, yes, obviously it's a survey for as Hayek pointed out we cannot possibly gain enough information to really measure something as complex as an economy. There is the idea that we should move more to tax data - but the problem with that is that we know very well that people lie about taxes.

But there's actually something much more important than this. GDP isn't what we're interested in. It's a proxy, an interesting and useful proxy but a proxy all the same.

What we want to know is "How well off are the people?" We want to know this so that we can consider whether what we're doing makes them better off again or not. And our problem with GDP is that we're measuring things at market prices. What people actually pay for things.

Yet we know very well that this is not the price at which people actually value something. If a producer were able to price discriminate so that we each paid exactly what something was worth to us then it would be of course. And they attempt this. VW sells much the same car under the Skoda, VW, Audi and so on brands, each at a different price, in an attempt to do such price discrimination. But it doesn't work entirely.

The usual rule of thumb is that this consumer surplus, this value that we gain but which we don't have to pay for, is about equal to recorded GDP. So our consumption value is really some 200% of recorded GDP.

Which is where our problem comes in. Because the digital world would appear to be changing that multiplier. WhatsApp appears in GDP as something like $30 million, $50 million. There's no sales of it, no revenue from it, just the cost of the engineers working on it. And yet this is something that a billion people use for their telecoms needs, or some of them. The value in actual human value as consumption is obviously more than $100 million a year.

We must therefore remember not only that GDP is a proxy for what we really want to know but also that it's becoming an ever less reliable one.

Food of the Future: Chinese Food Security and the Opportunities of Brexit

The old adage – “the way to someone’s heart is through their stomach” - has never been more pertinent to global security. With the world’s population now exceeding 7.2 billion (an awful lot of stomachs to fill) we require a mind-boggling amount of food. In fact, farmers will need to grow as much food in the next fifty years as they did in the last 10,000 years combined. And at a time when one in eight people on the planet is already chronically malnourished, this is clearly an issue that isn’t going to be resolved purely by traditional production methods. Resources are particularly limited in high economic-growth regions such as China, a country that has to feed 22% of the world’s population but which is endowed with only 7% of the planet’s cultivable land. With so many increasingly vociferous middle-class mouths to feed, it is unsurprising that food security is rapidly becoming the most contentious issue in Chinese politics.

Inspired in part by India’s “Green Revolution”, China has been keen to expand their area of influence in the agrichemical sector, and have been investing heavily in their own research into genetically modified technologies. As with many aspects of China’s economy, however, their GM industry is dominated by state-owned companies, reflecting the government’s political objective of securing domestic food supply through improving agricultural productivity.

The old adage – “the way to someone’s heart is through their stomach” - has never been more pertinent to global security. With the world’s population now exceeding 7.2 billion (an awful lot of stomachs to fill) we require a mind-boggling amount of food. In fact, farmers will need to grow as much food in the next fifty years as they did in the last 10,000 years combined. And at a time when one in eight people on the planet is already chronically malnourished, this is clearly an issue that isn’t going to be resolved purely by traditional production methods. Resources are particularly limited in high economic-growth regions such as China, a country that has to feed 22% of the world’s population but which is endowed with only 7% of the planet’s cultivable land. With so many increasingly vociferous middle-class mouths to feed, it is unsurprising that food security is rapidly becoming the most contentious issue in Chinese politics.

Inspired in part by India’s “Green Revolution”, China has been keen to expand their area of influence in the agrichemical sector, and have been investing heavily in their own research into genetically modified technologies. As with many aspects of China’s economy, however, their GM industry is dominated by state-owned companies, reflecting the government’s political objective of securing domestic food supply through improving agricultural productivity.

The economic and environmental opportunities that these revolutionary GM foods present are staggering, and potentially unlimited. So far, we have been unable to escape a trade off between the need to ramp up supply - in order to satisfy dramatic increases in demand - and the degradation this inflicts on our planet. Scientists purport that herbicides and pesticides, pumped over crops by farmers attempting to maximise yields, have disturbing environmental consequences and can actually reduce the productive potential of the land over time.

The fragile balance of the ecosystem breaks down rapidly as the concentration of ions (vital nutrients for healthy plant growth) in the soil is dramatically reduced, damaging plants’ immune systems and weakening their roots. The chemicals harm insect and microorganism species that play important, fundamental roles in the ecology of agricultural land: naturally limiting pest populations via the food chain mechanism and maintaining soil condition. Worse still, just as antibiotic resistance is one of the greatest threats to patients' safety, there are fears that organisms are also developing resistance to certain pesticides – a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions.

However, we are now living in a remarkable reality where it is possible to create pest resistant crops, eliminating the use of herbicides and thus averting the immunity crisis. The devastation to cotton crops as a result of the cotton bollworm is now just a memory to many Chinese farmers; in 2002, half the cotton grown in China was genetically engineered to produce a toxin poisonous to the terrible pest. Research undertaken by Wilhelm Klümper and Matin Qaim, published in the Public Library of Science, has found that, on average, such GM technology adoption has not only reduced chemical pesticide use by 37%, but increased crop yields by 22%. Substantial economic rewards can also be reaped; the study estimates that farmers who grow GM crops harvest profit increases of 68%. Modifications extend the shelf life of products, benefitting supermarkets that currently bin their revenues as a result of overcautious sell-by dates and consumer expectation of cosmetic perfection.

The economy benefits indirectly too, as a healthier workforce is created. Specific nutrients are introduced into crops to supplement paucities in the diet of a local population group. For example, the GM crop known as ‘golden rice’ has been engineered to enhance the levels of ß-carotene to tackle Vitamin A Deficiency (VAD), a condition disproportionately affecting children. Research has shown that in China alone, roughly 13% of children aged 0-6 years old suffer from VAD, severe cases of which can lead to blindness. This field is limitless and we are only just discovering other advantages, such as with new research into creating GM plants capable of producing vaccines.

A clear statement of the Chinese government’s serious intentions in ensuring adequate food supplies for the future is the recent announcement by ChemChina of their $43 billion bid for Syngenta, a Swiss firm, spun out of AstraZenca, a UK-domiciled chemicals corporation, specialising in pesticides and genomic research. If this acquisition gets regulatory approval, not only will it be the largest foreign investment ever made by a Chinese company, it will also mean that the combined ChemChina-Syngenta conglomerate accounts for more than a quarter of the world agribusiness market by revenue.

Since the opening of China to international trade in 1978, the sweeping market-economy reforms that were begun under Deng Xiaoping have successfully lifted 700 million people out of poverty and chronic hunger. The size of the middle class (defined as those with annual household income between $11,500 and $43,000) has grown exponentially from just 5 million households in 2005, to roughly 225 million households. The increasing affluence of China’s population has led to ever-increasing demand for protein-rich, processed-foods. McDonald’s is now frequently the restaurant of choice for Chinese families celebrating a special occasion, reflecting the growing westernization of the Chinese palate rather than any perception of the Big Mac as gourmet cuisine!

The dizzying growth of the Chinese middle class in the past decade has been accompanied by equally rapid urbanisation. Ten of the world’s top twenty fastest-growing cities are in China and the number of city dwellers now exceeds the rural population: a truly remarkable one-generation transformation of a traditionally agrarian society that would have bewildered Chairman Mao. As these cities and factories encroach and then consume the countryside, cultivable land has steadily diminished. This insatiable pursuit of economic growth regardless of externalities has, in places, resulted in environmental catastrophe. By some accounts, one-fifth of the country’s soil is now contaminated by unregulated industrial pollution. This cocktail of shrinking fertile land, increasing urban population drift and the relaxation of the one-child policy is a frightening one for China’s rulers.

As China is starting to suffer from diminishing marginal efficiency gains from its investment, avoiding famine on a scale even greater than that of the Great Famine of 1959-61 (when 14 million people died as a result of the Great Leap Forward) has become a primary objective. Lack of investment now into commercial agrichemical research and development would, Chinese leaders fear, stifle China’s economic growth. By failing to ensure a food supply for the city workers, the modern-day Great Leap Forward will be constrained. A nation, like an army, can’t march on an empty stomach.

Although the Chinese are at the cutting edge of research in agricultural biotechnology, having run more than 130 projects since the 1980s, rolling out nationwide commercial GMO schemes will still take years. Progress is often hindered by dislocation between state-sponsored GM research centres and commercial enterprises. Just as elsewhere in the world, there is vocal public opposition to these “freaky” and “unnatural” foodstuffs. Multiple shocking (and fatal) food scandals, involving everything from exploding watermelons to tainted formula milk, have received sensational coverage in the normally quiescent national media, rightly causing the public to be profoundly sceptical about the ability of food-safety authorities to enforce regulations.

Although public dissent in China towards government policy is traditionally muted, the leadership know that such events make it harder to sell the undeniable benefits of genetic modification. Given the pressure on the government to provide urgent solutions, momentum is growing: recent Five-Year Plans have announced ever-increasing government financial support to commercialise scientific innovation, with a special focus on genetic engineering. The ChemChina-Syngenta merger is only one, albeit highly visible, commitment to the Chinese government’s goal of eventually establishing food security for its entire population. Targeted propaganda campaigns to correct the information failure surrounding the perceived danger of GMOs should help to educate the public about the almost universal undeniably favourable stance on GMOs held by scientists and agencies, including the World Health Organization.

Anxiety about food insecurity in China (and in other developing nations with similarly large populations) could provide a massive impetus to UK agribusiness now it has left the EU. No longer constrained by the Common Agricultural Policy’s protectionist stance towards GMOs, Brexit gives UK scientists and agrichemical businesses the opportunity to become global leaders in this virtually limitless field. When the UK was tied to the EU’s autonomous food security programme, there was little incentive to fund research projects into GM crops. Throughout the EU’s history, there has only been one licence granted to allow the commercial production of genetically modified crops, which was over a decade ago. This anti-GMO stance in Europe resulted in 19 of the 28 EU countries banning their farmers from growing GM crops in October 2015. Even those countries that don’t implement the ban on GMOs are still required to seek the approval of the European Commission before they are allowed to plant any newly developed crop strain, and since the GM-sceptic countries are in the majority, they delay authorisation for years.

The bureaucracy involved in assessing whether new biotechnology practices are environmentally safe has meant that, in the cases of 21 safely tested GM crops, the entry to market of new GMOs has been delayed for a total of 44 years. These unjustifiable delays have been increasing since mid-2013, and are forecasted to have cost the European economy €9.6 billion due to the resulting trade disruptions. Frustrated by this deadlock, many European companies have simply abandoned attempts at submitting crops for review.

But the referendum gives the UK an unexpected opportunity to seize the initiative. Exiting the EU could revolutionise our farming practices and allow us to capitalise on the urgency of the Chinese to secure reliable food suppliers. The recent slowdown in the Chinese economy and the lack of suitable domestic investment opportunities has encouraged Chinese firms to look for profitable mergers abroad. A flourishing British agrichemical sector would be extremely attractive to China, both for investment and for security reasons. Despite having been restricted as a member of the EU from being able to profitably harvest GMO crops on our own soil, Britain’s strong pedigree in agricultural research has attracted all of the industry’s major players – the “Big 6” as they are known (BASF, Bayer, Dupont, Dow Chemical Company, Monsanto, and Syngenta).

Our outstanding reputation in the early stages of the research and development cycle has driven private investment. Syngenta, for example, employs around 2500 people in the UK across 11 sites, in particular investing nearly $200 million per year into their largest agrochemical R&D facility in Berkshire. The company, which turns over $1.25 billion annually, is capitalising on the powerful brains of British plant scientists – some of the best in the world. Although all attention is currently focused on the form exit from the European Union will take, the government should not ignore this immense opportunity, freed from EU suspicion and regulation. Collectively the “Big 6” spend around $4.7 billion each year on R&D, and the government would be wise to encourage greater investment, perhaps through infrastructure projects connecting the clusters of biotech firms that have appeared. The availability of grants for new research projects and the establishment of more dedicated enterprise zones would help Post-Brexit Britain’s standing in the global agriculture sector sprout tall.

Undoubtedly there will be opposition to supporting such a divisive initiative, just as there has been to fracking. But if the government is serious about rejuvenating the agricultural sector, after decades of mismanagement as a consequence of CAP regulation, it should consider how Brexit has freed us to consider radical solutions. Though we may be a long way ourselves from stocking genetically modified food on our supermarket shelves, the necessity to secure a reliable food supply in China is much stronger. Opening our country up to Chinese investment into our GMO trials would be an exciting enhancement of our trade relations with China.

What would it be like if the government really did run the economy?

It's very difficult indeed for us to map out exactly how it would all turn out if the government really were to run the economy in detail. Thus we need to try and find a comparator, somewhere that has two economic systems and we can observe the different outcomes.

We can of course think of the grand experiment that was the 20th century. Those places that had state socialism ran a race against those that used markets and the state socialism lost. But of course no one calls for such any more - at least we are continually assured.

But there are people calling for a democratic economy - that is, one where everything is decided through voting on committees. Others call for the bureaucratic economy, where the committees decide and there're even those absurdists who demand a Courageous State, where politicians decide each detail.

What we would like to find therefore is somewhere which has something like our market mix and right next to it something more like that state run and controlled economy so we can observe the different outcomes. Fortunately we have this - the United States. Government, planning, bureaucratic control, once again lose:

Imagine if the government were responsible for looking after your best interests. All of your assets must be managed by bureaucrats on your behalf. A special bureau is even set up to oversee your affairs. Every important decision you make requires approval, and every approval comes with a mountain of regulations.

How well would this work? Just ask Native Americans.

The federal government is responsible for managing Indian affairs for the benefit of all Indians. But by all accounts the government has failed to live up to this responsibility. As a result, Native American reservations are among the poorest communities in the United States.

Hmm, perhaps government isn't the way to run life and the economy then?

What’s to be done with the House of Lords?

Two recent events have brought back into prominence that hardy perennial House of Lords Reform. The first event was former prime Minister David Cameron’s disastrous Resignation Honours List. The second event was the vocal threat by Baroness (Patience) Wheatcroft that she and a claque of similarly-ignorant peers would seek to block Britain’s forthcoming Brexit and do so from the (unelected) House of Lords.

Because of all that the new prime minister Theresa May has been obliged to raise the priority of House of Lords Reform, as if she hasn’t got enough on her plate already. So as a helping hand, here are the seven basic principles for her and her advisers to consider:

1. We always need a Second Chamber to keep tabs on the first.

2. The British people should have the last say who sits in it. Ten Downing Street should have nothing to do with choosing virtually all its members.

3. Its members should each only ever be elected once, so they are not constantly buttering up their voters seeking to get re-elected. They have independence of mind. Bruce Tulloch examined that distorted motivation in an Institute of Economic Affairs pamphlet published decades ago. He called the problem “The Vote Motive”.

4. Currently the Lords has far too many members. As with all legislatures 250 is ideal, 400 should be tops. The current 797 is utterly ridiculous.

5. It must not become a political clone of the House of Commons.

6. Its members should possess a worthy level of experience and expertise and be expected to lead the House on their specialist areas. In the process they should expose the House of Commons for what it is: far too many bumbling over-opinionated ignoramuses who succeed only in bringing the whole of politics into disrepute.

7. The major political parties should have as little as possible to do with its membership.

***

None of those seven points is even remotely original. I first heard them in 1974 at a formal Chambers of Commerce gathering, almost half a century ago. They were expounded by a very clever, original-minded accountant from Birmingham called Bruce Sutherland.

Bruce held the interesting distinction of being chairman of both the Chambers of Commerce and also the CBI Taxation committees - the only person to straddle both. In passing one might fairly observe that Patience Wheatcroft was working in the same building at the same time as a junior journalist of the London Chamber of Commerce's monthly magazine.

So now let’s move on from that, adding in a few tweaks of my own. The most important question, as always, is how anyone gets on a ballot paper, especially for the House of Lord. All too often, it’s simply a shoo-in after that anyway. Ten Downing Street often prefers, or rather in the pre-crony era used to prefer, experts in their own particular field, and not mere sycophants. I quite like that previous idea as well, so let’s stick with it.

8. So if we want clever surgeons or clever architects to become candidates for the Lords (they are not yet members, of course) then let the Royal College of Surgeons, or the Royal Institute of British Architects choose them from among their own number. They, better than anyone, know who would be the most suitable.

Let all the royal-somethings get a shout, plus bodies such as the Chambers of Commerce, the CBI, the legal profession, the military, the churches, the TUC and indeed the Commons and the Civil Service itself. Indeed that could well give the Palace something to think about as well. If a few eccentric-somethings get on the list it hardly matters because none of them will go any further.

In effect, the process of selecting future members of the House of Lords has been Privatised.

9. And at that point we could also re-admit all the hereditary peers to the process as well. Some of them are very clever, almost more clever than parliament deserves. Ralph Percy, aged 59, Duke of Northumberland, does an excellent job with all his highly-skilled farming mates. He lives in Alnwick Castle and all around him are the arable farms of his tenants.

Northumberland is very rich and I wager most of his tenant farmers are millionaires too. They run their farms on a very large scale, essentially organising a know-how co-operative. Not a fool among them; Ralph Percy would never allow that.

The late Gerald Grosvenor, Duke of Westminster, was one of the world’s most expert - and philanthropic - property developers. I would have a man like that as my Member in the Lords any day of the week. Some of the world’s finest inner suburbs of Mayfair, Belgravia and Pimlico were mainly the Westminster’s own work. It was the farming family of the Grosvenors who spotted the potential of their lands and turned themselves into Britain’s richest Dukedom in the process.

Therefore we need about eighty constituencies, substantially more than there are states in the USA. In a sense it is an extension of the way each American state has a Senior and Junior Senator, and I consider that a wise principle we ought to adopt over here; it would make for admirable continuity.

The insanity of the JRF's latest poverty campaign

We've kept something of a wary eye on the Joseph Rowntree Foundation's ruminations on poverty over the years. Near a decade back they started that idea of the living wage. Ask people what people should be able to do if they're not in poverty. Along the lines of Adam Smith's linen shirt example. So far so good - but it was a measure of what is it that, by the standards of this time and place, people should be able to do and not be considered to be in poverty.

In this latest report of theirs they are saying that if the average family isn't on the verge of paying 40% income tax then they're in poverty.

This is not, we submit, a useful or relevant measure of poverty. But it is the one that they are using. Here is their definition:

In 2008, JRF published the Minimum Income Standard (MIS) – the benchmark of minimum needs based on what goods and services members of the public think are required for an adequate standard of living. This includes food, clothes and shelter; it also includes what we need in order to have the opportunities and choices necessary to participate in society. Updated annually, MIS includes the cost of meeting needs including food, clothing, household bills, transport, and social and cultural participation.

JRF uses 75% of MIS as an indicator of poverty. People with incomes below this level face a particularly high risk of deprivation. A household with income below 75% of MIS is typically more than four times as likely to be deprived as someone at 100% of MIS or above. In 2016, a couple with two children (one pre-school and one primary school age) would need £422 per week to achieve what the public considers to be the Minimum Income Standard, after housing and childcare costs. A single working-age person would need £178 per week

Having an income that is just 75% of these amounts –£317 for the couple and £134 for the single person – is an indication that a household’s resources are highly likely not to meet their needs. The further their incomes fall, the more harmful their situation is likely to be.

So that's £16,500 a year for the high risk of deprivation and £22,000 a year for poverty. But note (this for the average family, two plus two) that this is disposable income after housing and childcare costs. We must add those back in to get the other definition of disposable income, the one that ONS uses.

Average rent is £816 a month, average childcare costs are £6,000 a child a year.

That's therefore £38,500 a year or £44,000 a year in actual consumption possibilities for such a family. That higher number marks poverty, the lower potential deprivation.

As ONS tells us (and this is disposable income, after tax and benefits, before housing and childcare) median household income in the UK is:

The provisional estimate of median household disposable income for 2014/15 is £25,600. This is £1,500 higher than its recent low in 2012/13, after accounting for inflation and household composition, and at a similar level to its pre-downturn value (£25,400)

And do note that ONS definition:

Disposable income:

Disposable income is the amount of money that households have available for spending and saving after direct taxes (such as income tax and council tax) have been accounted for. It includes earnings from employment, private pensions and investments as well as cash benefits provided by the state.

The JRF is using a definition of poverty that is higher than median income for the country. This is insane. It gets worse too. The band for higher rate income tax starts at £43,000. The JRF is defining a two parent, two child, household beginning to pay higher rate income tax as being in poverty.

To put this another way, a British family in the top 0.23% of the global income distribution for an individual is in poverty and one in the top 0.32% of that global distribution is deprived. Yes, after adjusting for price differences across countries.

The British population is some 1% of the global population. It's not actually possible for us all to be in anything more than the top 1% of the global income distribution.

This simply is not a valid manner of trying to define poverty.

It's wonderful how this profit motive thing works, isn't it?

That rocket which blew up was carrying a satellite aimed at aiding Facebook in delivering free, if limited, internet to the poor of the world. We are told this is a bad thing:

But if we’re slightly more cynical about the whole endeavour, it’s not hard to see why Facebook might be so keen to provide these services beyond its possibly genuine desire to create a more connected world. Facebook’s user base has reached near saturation point in the US and Europe, making countries such as Nigeria and India potential goldmines when it comes to new sign-ups. More users, and more user data, benefit Facebook in one extremely simple way – financially.

Like it or not, this financial consideration is a significant factor in the way that the company both provides its services and limits access to others.

We see the same facts and consider them rather differently. In pursuit of filthy lucre, of gelt, a profit hungry organisation is now providing free, even if to a limited version of it, access to the internet to the poor (or perhaps will be when they can manage to loft a satellite). In the absence of this profit hungry company, motivated by absolutely no more that the desire to stack the cash ever higher in the vault, there would be no such internet access for the poor, limited or not.

At which point Hurrah! for greed and the profit motive say we. And it puzzles us deeply that people will fret over the motivation and not look instead at the actual result.

Then there's this of course:

So far so good, right? Well, kind of. Providing access to the internet is a noble cause, particularly in parts of the world where it is severely limited or even non-existent. But should this infrastructure belong to a private company like Facebook, or should it be state-owned and maintained? Far be it from me to question the true nature of CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s philanthropy, but no matter how charitable a cause Facebook is championing, its primary aim is to make money – often from monetising its users’ data.

That's just a rerun of an ancient argument. When steel and coal were the big important industries then the left said that government must control them. When the telephone landline network was important then the state must provide that. Now that the internet has mushroomed up entirely free of state interference (except, perhaps that starting point in Arpanet) and is important then of course the state must provide and or control it. Because anything important must be controlled by the state, no other reason.

But we do admit that we rather like, even though we disagree with, the underlying economic argument being used.

"So, these blokes over here will provide this infrastructure and service at their own expense and for free to users. Anyone who wants to build the same or similar is of course entirely free to do so."

"No, we must tax the people so the state can build it."

"Err, why?"

"Because."

Richmond Times-Dispatch the largest-circulation newspaper to ever endorse a Libertarian Party candidate

As far as I can tell, the Richmond Times-Dispatch has a higher circulation than any other newspaper to endorse a Libertarian Party candidate for US President, something it did on Saturday when it threw its hat into the ring for Gary Johnson.

Here's what it said:

In this autumn of our electoral discontent, hope springs, as it so often does in the American republic, from unexpected precincts. Much of the country is distressed by the presidential candidates offered by the two conventional political parties. And for good reason. Neither Donald Trump nor Hillary Clinton meets the fundamental moral and professional standards we have every right to expect of an American president.

Fortunately, there is a reasonable — and formidable — alternative. Gary Johnson is a former, two-term governor of New Mexico and a man who built from scratch a construction company that eventually employed more than 1,000 people before he sold it in 1999. He possesses substantial executive experience in both the private and the public sectors.

More important, he’s a man of good integrity, apparently normal ego and sound ideas. Sadly, in the 2016 presidential contest, those essential qualities make him an anomaly — though they are the foundations for solid leadership and trustworthy character. (At 63, he is also the youngest candidate by more than half a decade — and is polling well among truly young voters.)

I don't think Gary is going to win, and I usually think you should vote for the lesser of two evils—or save the time, if you're not in a marginal state—but there nevertheless is something very cheering about this endorsement. I hope that a solid vote for Johnson (or a solid expected vote) will push the other candidates toward more libertarian policies.