Russia murders dissidents

Alexander Litvinenko was a one-time officer in the Russian FSB, successor to the KGB intelligence service. His task there was dealing with organized crime. He died in London on November 23rd, 2006, having been poisoned by Kremlin agents with radioactive polonium-210.

What aroused Vladimir Putin’s anger was that Litvinenko had identified links between the Russian hierarchy and organized crime. He coined the term ‘Mafia state,’ and went public at a Moscow press conference with details of officially ordered or sanctioned murders of political dissidents and reporters.

He was dismissed from the FSB on Putin’s orders, and put on trial for “exceeding the authority of his position.” He was acquitted, and fled to Britain vis Turkey with his family before new charges could be brought against hm. In the UK he became a writer and a journalist, and also, according to his widow, worked as a consultant with MI5 and MI6, helping them combat Russian organized crime in Europe. He became a UK citizen.

On the day he fell ill, Litvinenko had met another former Russian agent, Dmitry Kovtun, who was later found to have left Polonium traces in both the house and the car he had recently used in Hamburg. After Litvinenko’s death, a British murder enquiry identified Andrey Lugovoy, a former member of Russia's Federal Protective Service, as the prime suspect. The United Kingdom demanded that he be extradited to face trial, but this was denied, as Russia does not extradite its citizens.

A further British enquiry concluded in 2016 that he had been murdered by the Russian FSB, probably with the approval of Vladimir Putin himself, and Nikolai Patrushev, at the time FSB Director. His widow confirmed that her late husband had provided useful information to MI6 about senior Kremlin figures and their links with organized crime.

There are obvious parallels with the attempted murder of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in March, 2018, in Salisbury. Skripal had worked with UK intelligence as a double agent until he was caught and sentenced to 13 years in a penal colony. He came to the UK after a spy swap, and took British citizenship, He and his daughter were critically ill, but recovered after intensive care. The nerve agent Novichok was identified as the toxin. Two Britons later became seriously ill, and one died, after they picked up the discarded scent spray that had been used in the attack.

The UK identified the two people who had carried out the Salisbury attack, and was supported by 28 countries when it announced punitive measures against Russia. A total of 153 Russian diplomats were expelled. The culprits were identified as Colonel Anatoliy Chepiga and Dr. Alexander Mishkin, both ranking officers in the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence. The operation was almost certainly sanctioned by Putin himself. They appeared in a laughably inept interview on Russian TV, talking of the wonders of Salisbury Cathedral, which they claim they had just visited as tourists.

Two facts are significant about both poisonings. In both cases the victims had already revealed all they knew. They were targeted in revenge attacks, and in both cases an exotic poison was used that could only have originated from Russia. Russia is telling the world that it has the ability and the resolve to kill anyone who it feels has acted against it. It further lets the world know that it can do this with relative impunity.

The incidents expose Putin as a thug and a bully, and someone not to be trusted. It might be appropriate for him to be tried in absentia in a public trial for these murders and attempted murders. Witnesses could be called upon to testify, and a verdict reached that would show the world what he is, and give some small satisfaction to the relatives of his victims.

Lidl and the living wage

We find this interesting:

Lidl is giving its UK staff a pay rise worth £10m with a higher hourly rate likely to propel it to the top of the supermarket pay league table.

The retailer said 19,000 employees would get a pay rise in March when its hourly rate would move from £9 to £9.30 outside London and from £10.55 to £10.75 in the capital. The rises match the higher rate announced by the Living Wage Foundation – the charity which sets the voluntary measure – last week.

This is consistent with the basic analysis of higher wages. Employers who use labour more productively can - and often will - pay higher wages. The other side of the same statement being that those who employ more productive labour employ less labour. That’s what more productive means, that you get the same output from the input of less labour time.

That is, higher wages mean fewer have jobs. Our example here, Lidl, is famed for cutting back on the labour used to provide retail services. Shelf-stacking is in fact box-stacking, not individual items. Barcodes are printed on every side of the packaging to reduce till time.

Lidl is a labour-light method of retail. Which is why they can - and do - pay those higher wages.

But it’s this which we find absolutely fascinating:

Katherine Chapman, the director of the Living Wage Foundation, said: “It’s a great to hear that Lidl will be going beyond the government minimum and paying the new real living wage rate to employees. However, as Lidl is not accredited with the Living Wage Foundation, we can’t be sure that its subcontracted staff, such as cleaners, trolley collectors and warehouse workers, are paid this rate.”

We’re rather straying into the realms of religion here rather than economics or justice. Actions don’t matter so much in receiving that imprimatur.

To find out more details about the criteria for accreditation, read the FAQs. There is a sliding scale of accreditation fees depending on the size of your organisation.

Much more important is paying the tithe to keep the Tarquins and Jocastas in their comfortable offices.

The medieval Catholic Church would have been proud of that, home as it so often was to the extra, superfluous, offspring of the upper classes looking for a comfy berth.

Thomas Cook and package tours

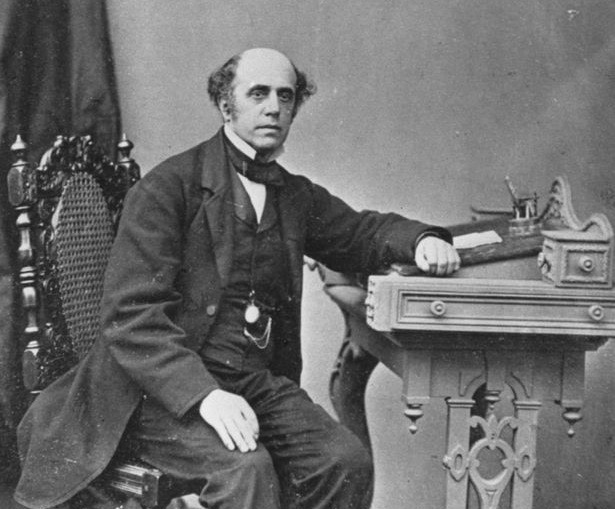

Thomas Cook virtually invented modern tourism. He was born on November 22nd, 1808, in the village of Melbourne in Derbyshire. He started work aged 10, first as a market gardener, then as a cabinet maker.

He saw the possibilities the new railways offered, and conceived the idea of taking people in groups on them. He first took 500 people from Leicester to Loughborough for a temperance rally, charging them a shilling (£0.05) for the round trip. He later took 350 people from Leicester on a tour of Scotland, then 150,000 people to London for the 1851 Great Exhibition.

In 1855 he undertook his first foreign tour, taking two groups on a circular tour of Belgium, Germany and France, ending in Paris for the French Exhibition. He later introduced ‘hotel coupons’ in counterfoil books, to be traded for hotel stays and meals at places on the Thomas Cook list. These were the first travellers cheques, and became big business.

By now his Fleet Street shop was selling travel accessories such as luggage and guide books, and he’d entered partnership with this son as “Thomas Cook & Son.” His package holidays had ushered in an age of mass tourism, opening up the Continent to British visitors, and Britain to tourists from abroad.

After his death the business passed to his sons, then grandsons, and remained in the family hands until 1928. It became one of the biggest travel firms in the world, adapting itself to the emergence of mass air travel to supplement. It went under just two months ago owing to what analysts declared was poor financial management. There was still money to be made from holidays, but the firm had taken on too much debt and was no longer able to meet its obligations. When it went out of business on 23 September, it was about £1.7bn in debt to its banks with a further £1.3bn owed to suppliers.

A further factor was competition. Newer, leaner firms were undercutting its prices and taking market share from it. This is what the market does. It is part of the constant churn as new products and processes enter the market with new competitors. Ways are found to cut costs, and those firms which lag behind in doing so find themselves displaced by those which are quicker to embrace the new opportunities.

It was sad to see Thomas Cook go, especially with so many job losses. The firm had a distinguished history and was embedded into UK holiday culture. But many famous household names have gone the same way, and others undoubtedly will. A look at the top 100 FTSE companies over time shows this churn, as newer names replace the familiar ones. The churn causes localized distress, usually brief, but new opportunities and better value result from it.

Selling the NHS - What do you think we'd get for it?

A consistent claim at present is that - it being election season we’ll not identify who - some would sell the NHS off to American corporations. Which raises an interesting question really, how much would we get for it if we did?

As both parties tried to seize the initiative over the NHS, Corbyn at one point brandished a document he claimed showed that US negotiators hoped to secure full access to Britain’s health sector as part of a bilateral trade deal after Brexit.

“Full market access for US products to our National Health Service. You’re going to sell our National Health Service to the United States and big pharma,” he accused Johnson.

Full market access would mean American corporations would be treated just like any other supplier to the NHS. It does, after all, buy bandages, aspirin, food for the patients and the canteens and so on. Quite why allowing more people to bid for such contracts is a terror is unknown to us.

But think of trying to actually sell it. Flogging off the hospitals, the clinics. What would we get for it?

Sure, there are assets there but they’re not all that valuable without an income stream to cover their costs. That income stream currently being tax revenues. That is, the NHS, without its tax funding, is worth nothing more or less. Things that are worth nothing we find it very difficult to sell.

So, we could try and sell the NHS, sure. But to do so we’d have to insist that we were going to continue to fund it from general tax revenues. At which point, well, what would then have changed? We’d have a tax funded health service just as we do now. The intervention of those American corporations would just be a different set of managers handling the income stream and the assets. Which doesn’t strike us as being all that much of a terror.

Note what selling the NHS, lock stock and barrel, would not do - create that same set of employment based health insurance.

At which point we’ve two possible outcomes. We don’t continue tax funding and we can’t sell it, we do continue tax funding and it’s pretty much as it is. Thus we struggle to understand even what the claim, the allegation, is.

Oh, sure, we understand the emotional tug of the claim upon those British heartstrings. But surely we don’t think that appeals to irrationality are the way to manage 10% of the British economy.

Do we?

Economic warfare

The Berlin Decree, issued by Napoleon on November 21st, 1806, declared economic warfare on Britain. The British Order in Council of six months earlier had started a blockade of French ports; now France responded by banning all contacts and commerce with Britain. British subjects found in France or its allies were to be seized, as were British goods and merchandise. Vessels violating this order were to be confiscated along with their cargoes.

Napoleon thought to force Britain to surrender by stopping its industries from trading with continental Europe. The lack of foreign gold coming in for its exports would bankrupt Britain’s Treasury, he supposed. His “Continental System” might have looked plausible in theory, but was difficult to enforce in practice over the large landmass he controlled. Furthermore, it was unpopular among the peoples of Europe, and some nations unilaterally ceased to comply with its terms.

Smugglers readily exploited the blockade because British goods were welcomed on the Continent. This was especially rife in Spain and Portugal, prompting Napoleon to invade Spain to enforce it, then Russia when the Tsar withdrew his country from it. His big defeats in both Spain and Russia ultimately led to his demise.

The British economy suffered much less because Britain had command of the seas and could engage in transatlantic and colonial trade. The Continental ports never recovered their position because of the loss of trade and the industries dependent on it, such as sugar refining and shipbuilding. Far from ruining Britain, the Continental System ultimately ruined France.

The fate of Napoleon’s Continental system calls into question the whole effectiveness of economic warfare, which today takes the form of sanctions. Sanctions against a country designed to pressure its government generally hurt its poorer peoples most by depriving them of cheap goods, and hurting its financial ability to provide the public services that poorer people often depend upon.

This is the main reason why sanctions today are often applied to named individuals in foreign governments, and to particular corporations, rather than to countries as a whole. There is much dispute over their effectiveness. They seem to work in some cases, but not in others, and it seems to depend on the size and type of economy involved. Some analysts doubt that sanctions against Russia following its annexation of the Crimea have had much effect on restraining the actions of its government. On the other hand, sanctions against Iran seem to have had a major impact on its economy, stirring up resentment of its government by its people.

When a country violates international law, or reneges on agreements it entered into, there is a strong desire of those affected by this to do something in response. Short of armed intervention, the imposition of sanctions presents itself as a form of punishment, or a means of forcing the recalcitrant government to the negotiating table. It is a blunt instrument, though, and generally harms both sides. The countries that use them sometimes commit the fallacy of “We must do something,” feeling that to do something ineffective is better than doing nothing at all. In reality, it isn’t.

The annoying thing is that Iran is trying to do the right thing here

Not in its totality, no, obviously not, but in this particular specific the government of Iran is trying to do the right thing. To switch subsidies from things to people:

Iran’s government has begun rushing out promised direct payments to 60 million Iranians, in a sign that the regime has been spooked by the scale of protests against petrol price rises announced last week.

In some cases petrol prices are being raised by as much as 300%. Unrest continued throughout Iran on Monday and internet access remained blocked for a second day.

Videos smuggled out of the country showed municipal buildings and banks being torched and large traffic jams as drivers blocked roads. The clashes seemed fiercest in the cities of Shiraz and Ahvaz rather than in Tehran As many as 1,000 people have been arrested.

In announcing the price rise on Thursday, the government said it was not seeking to raise state revenues but instead undertaking a complex switch in government subsidies.

It’s entirely possible to argue against subsidies at all. It must be possible because we make that argument ourselves often enough. But if there are going to be subsidies then it’s vastly better for it to be a subsidy of money to the poor than it is to be one to a certain product for all.

In Iran the petrol price is subsidised, substantially. It used to be even more, along with natural gas in fact. And there was a change, to instead of subsidising energy - Iran is one of the top three such subsidisers to fossil derived energy in the world - give people the amount to spend as they wished.

The advantage is that we all enjoy agency. Give us the money for us to deploy as we wish and we’ll gain greater value for that same cost to the exchequer. Simply because we are able to expend those resources on what we’d like, not on what politics thinks we should get.

The basic point is well known, to the point that the US Census readily admits it. Poor Americans value food stamps, or Medicaid, at less than it costs to provide them. They would be made richer if they simply got the cash instead. It is also this which explains why there’s a black market in food stamps. People value, say, nappies, more than they do food and will exchange money which works only for for for that which works for nappies at a substantial - 50% - discount. Diapers are in fact the major item paid for with illegally converted to cash food stamps.

The Iranian government is actually trying to do the right thing here, make everyone richer, by moving subsidies from things to people.

War criminals brought to justice

It used to be the case that tyrants could torture and murder their own subjects, and those they conquered, with impunity. That all changed on November 20th, 1945, when the War Crimes Tribunal began its hearings at Nuremberg, following the end of World War II.

The military tribunals were held by the Allies under international law, in order to put on trial 24 of the leading Nazi political and military leaders who had planned or participated in mass murders and other war crimes. They marked a major advance in international law because they put on trial people who had committed acts that were not illegal in their own countries at the time, but were deemed to be crimes against humanity.

Many of those most guilty of such crimes could not be tried because they were already dead. Hitler had shot Eva Braun and then himself. Goebbels and his wife had poisoned their six children before killing themselves. Himmler, although captured, had swallowed cyanide concealed in a false tooth when he was about to have his mouth examined. Bormann was tried in absentia because they did not realize he was already dead.

Amongst those who were tried, the most prominent was Goering, who was convicted and sentenced, but escaped the hangman’s noose by taking cyanide in his cell on the eve of his execution. Of the 24, 12 were sentenced to death, and 10 were hanged on October 16th, 1946. The two not hanged were Bormann and Goering, both already dead.

The Nuremberg trials were the first to mention genocide, “the extermination of racial and national groups, against the civilian populations of certain occupied territories in order to destroy particular races and classes of people” (count three, war crimes). They led in the years that followed to the establishment of an international jurisprudence for crimes against humanity and war crimes. The outcome was the creation of the International Criminal Court, the international tribunal that operates in The Hague, with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for such crimes.

The legacy of the Nuremberg Tribunal is that those who inflict crimes against humanity can be brought to justice. The knowledge that this could happen might restrain some people from committing acts of barbarism they might otherwise hope to perpetrate with impunity. The knowledge that those who do these things can later have justice meted out to them affords the world some satisfaction that humanity is no longer prepared to tolerate the mass cruelty and savagery that it once had no recourse to deal with. It is another sign that we are less passive about violence, and that “The Better Angels of our Nature” have made another advance towards a more civilized life.

We disagree entirely with Berkeley Group's Tony Pidgely over land hoarding and planning uplift

This is entirely the wrong solution:

One of Britain’s top housebuilders has backed radical reform of property laws to reverse the decline of home ownership by ending the hoarding of land and triggering a new wave of development.

Tony Pidgley, the founder of Berkeley Group, said landowners and developers should be forced to share “planning uplift” with local authorities.

The move would upend the residential construction industry but Mr Pidgley said the system is “in dire need of reform” to meet demand for hundreds of thousands of new homes.

“We need a central body that buys land, awards planning permission, then passes on the returns to the local community,” he said. “The whole of society should capture that value – it’s about decency.”

This makes no sense to us at all. The aim should be that there’s no planning uplift, not that the gain is shared communally.

Start back at the beginning. We have an artificial restriction upon who may build what, where. That restriction leads to there being value in having the permission to build something, somewhere. The value comes purely and solely from that restriction.

The result of this is that people have to pay very much more to live somewhere than they would without that set of artificial and entirely human, bureaucratically, created restrictions. We wish it to be cheaper for people to live somewhere. Thus we should be killing off the price rise caused by the restriction by killing off the restriction.

Shuffling around who gains that value created by the artificiality of the system doesn’t change that people have to pay more to live somewhere. That is, communal planning gain doesn’t solve our actual problem. Reorganising the system so that we issue more planning permissions, their value thus declining, would solve our problem.

Thus the answer is to issue more planning permissions until there is no planning gain at all. Or, as we’ve noted a certain number of times before, blow up the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 and successors.

Arguing about who should get a slice of the pie when there shouldn’t be a pie to be shared at all isn’t dealing with the root problem here. Why don’t we actually try to solve the thing instead of shuffling it?

Lincoln’s words at Gettysburg

On November 19th, 1863, US President Abraham Lincoln delivered at Gettysburg in Pennsylvania a speech of 271 words that has resonated through the culture of the United States and of the liberal democracies throughout the world. It was the famous Gettysburg Address, delivered at the dedication of the Soldier’s National Cemetery, four and a half months after the victory there of the Union army over that of the Confederacy.

Edward Everett, a former senator, governor of Massachusetts, and president of Harvard, and regarded at the time as America’s best orator, delivered a two-hour oration before Lincoln's short remarks. Everett’s speech was fine, but was eclipsed by the brief eloquence of Lincoln’s short address.

Lincoln had travelled by train with some of his cabinet and staff. His assistant secretary, John Hay, noted that Lincoln looked pale, haggard, and unwell. It was a correct observation, for Lincoln was later diagnosed with a mild case of smallpox.

Contrary to myth, the speech was not written on the back of an envelope, or put together in moments. It was carefully crafted and corrected, and touched the bases of what the Union soldiers had been fighting for - the preservation of that Union and the values that were embedded in its birth.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

America had been established as a counterblast to the autocracies and tyrannies of Europe. It was to be a nation governed by its people, and although many of those founding fathers and early presidents were slave owners, it was now fighting a costly civil war to assert its commitment to universal liberty and equality before the law for all Americans. People had died in this cause, and Americans were being reassured that their sacrifice had been worthwhile, and was honoured accordingly.

“…we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The entire text of the speech is engraved into the South wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC. It has been quoted and alluded to many times, but rarely more powerfully than when Martin Luther King delivered his “I have a dream” standing on the steps in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

People in several countries in the world today are demonstrating in the streets, some fighting, some dying, and they do so in the cause that Lincoln so eloquently expressed on that November day - government by the people instead of by those with the power to oppress.

How can the NHS be running out of heroin?

Jeremy Corbyn tells us all that he’d never allow a free trade agreement with the United States because this would mean the NHS would have to pay more for drugs:

There is a plot against our NHS. Boris Johnson is engaged in a cover-up of secret talks for a sell-out American trade deal that would drive up the cost of medicines and lead to runaway privatisation of our health service.

US corporations want to force up the price we pay for drugs, which could drain £500m a week from the NHS. And they demand the green light for full access to Britain’s public health system for private profit.

Our public services are not bargaining chips to be traded in secret deals. I pledge a Labour government will exclude the NHS, medicines and public services from any trade deals – and make that binding in law.

We have to admit that we can’t quite see the mechanism here. Freer trade means a reduction in the barriers to people offering us their production. As buyers that means we get offered more sources of supply. Quite how more people being able to offer us their goods increases prices we can’t quite see.

But then perhaps the NHS should be paying more for drugs anyway?

The NHS is running short of dozens of lifesaving medicines including treatments for cancer, heart conditions and epilepsy, the Guardian has learned.

An internal 24-page document circulated to some doctors last Friday from the medicine supply team at the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), headed “commercial-sensitive”, listed many drugs currently hit by shortages at the NHS.

As we all know - at least should - the NHS negotiates down the prices it pays for drugs from whatever source. And one of the things about offering prices lower than other people for your purchasing is that at times people will find better places, other people to sell to. A shortage is in fact evidence that the price being offered is too low.

Which brings us to this, one of the drugs in that short supply:

Diamorphine: “insufficient stock to cover full forecasted demand in both primary and secondary care”.

Diamorphine is heroin. It’s nothing else either. And a regular complaint about that drug is that there are copious stocks in every city, town, village and hamlet in the country.

The market, paying whatever is the market price - even through that cost of illegality - provides enough heroin to float us all off into feeling no pain at all. The NHS manages, at that very same time, to have a shortage of the same stuff. You know, perhaps there’s something wrong with the price the NHS is paying? It’s too low perhaps?