Yes, of course governments should target happiness

It’s an odd question even for people to ask, whether governments should target happiness or GDP. The answer is so obvious that why even bother to ponder it, happiness is the point:

Is the relentless reach for economic growth coming at the expense of our personal happiness and well-being?

It is a question that is being asked around the world and has even inspired part of the Liberal Democrat manifesto. It has proposed a "well-being budget" that would base decisions on factors in addition to growth, an idea borrowed from New Zealand.

Iceland’s Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir also revealed on Tuesday that her country will be the latest to focus on well-being over gross domestic product (GDP).

“An Icelandic poet actually said famously that having sex with your wife does not count in GDP but having sex with a prostitute does so that should really make us think,” she joked...

The answer to that little conundrum being that the roughly 2 to 3% of men who regularly use prostitutes (a reasonable estimate, lifetime incidence is usually measured at around 10%) find that their happiness is so enhanced, the other 97% do not. Which is that vital clue to what the pursuit or targeting of happiness should actually be about.

As economists keep pointing out, utility - not the same as happiness itself but the jargon for something similar - is an entirely personal thing. There are, after all, those who appreciate Simon Cowell. To target happiness is thus to be allowing the maximal freedom to all to maximise their own utility.

That is, happiness maximisation means the classically liberal state where intervention is only allowed, let alone justified, when the pursuit limits the ability of another to so pursue.

We having an nice little example of this too:

Almost every worker in the country is happy with the terms of their employment, despite the rise of "gig" work and a long-running row over zero-hours contracts.

Around 99pc of workers across Britain are satisfied with their contract according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), with very minor variations depending on the type of employment. For example, this falls to 97pc for men in part-time jobs.

It is further evidence that the common opinion that zero-hours agreements are rampant and unpopular is false. The contracts offer flexibility to around 900,000 workers and their employers, but have become the focus of much political criticism in recent years.

Leave people alone to get on with things as they’ll pursue their own happiness as well as is possible within the constraints of physical reality. At which point, well, job done, isn’t it?

That is, the secret to the political maximisation of happiness is that politics and politicians potter off and do something else - preferably nothing - other than defend the rights of the citizenry to the pursuit of happiness and leave the rest of us to the delights of chacun a son gout.

That this is also the method of GDP maximisation is just a happy circumstance.

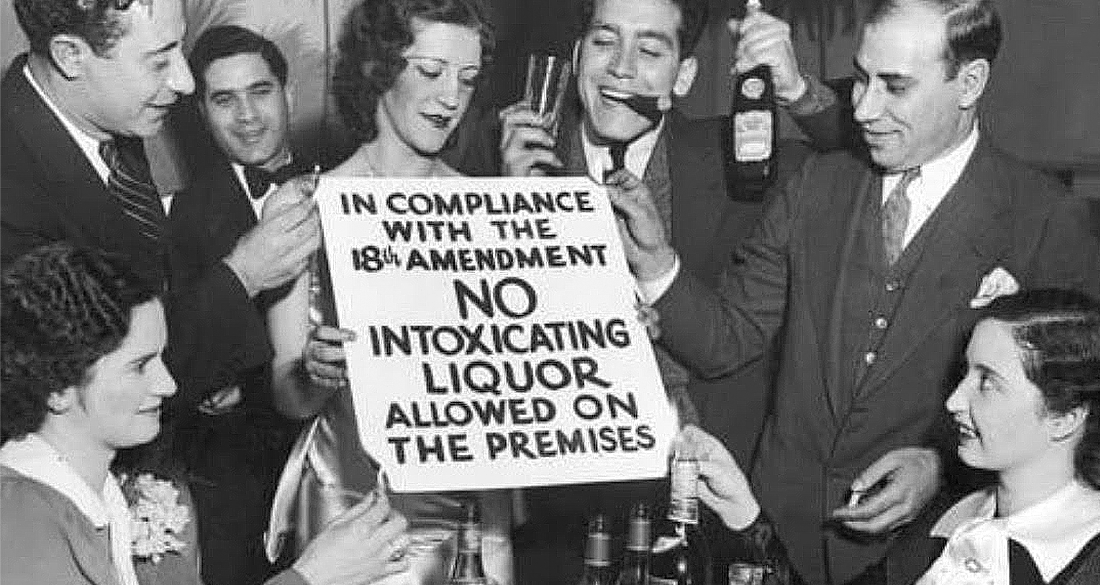

The end of Prohibition

America went dry on January 17th, 1920, as the Eighteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution, inaugurating Prohibition. Just under 14 years later, on December 5th, 1933, the Twenty-First Amendment was added to the Constitution, repealing the Eighteenth and ending the era of Prohibition.

Prohibition was a disaster, in that it was an attempt to force the views of some, led by pious protestants and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, upon the whole of America. The Anti-Saloon League was opposed by many Catholics and German Lutherans, but German Americans had lost prestige during the First World War, and were unable to prevent the victory of the “drys.”

Criminal gangs were prepared to supply illicitly what the government had made illegal, and soon dominated the illegal supply of beer and spirits in most US cities. Booze was smuggled across borders and made domestically. A week after prohibition came in, small portable stills went on sale throughout America. Crates of liquor were smuggled in from Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean.

Doctors lobbied to be allowed to prescribe alcohol for “medicinal” purposes, and between 1921 and 1930, they earned roughly $40 million from whiskey prescriptions. BY 1926 the number of illegal “speakeasy” drinking establishments was put at between 30,000 to 100,000 in New York City alone. Cheap bathtub hooch had its raw quality concealed by a fashionable taste for cocktails, and just as government poisoned industrial alcohol to prevent its use for drinking, so gangs employed chemists to reverse the process and make it harmless.

Britain’s visiting Prince of Wales came back from Canada reporting a song he’d learned there:

Four and twenty Yankees, feeling very dry,

Went across the border to get a drink of rye.

When the rye was opened, the Yanks began to sing,

"God bless America, but God save the King!"

Prohibition made a mockery of the law and set ordinary Americans against the police and the law. Gangsters made huge sums from bootlegging, and bought judges and entire police departments. Al Capone was cheered at baseball games as a hero who gave people what they wanted. Gang slaughter came in as rivals killed each other in territorial fights for the vast profits to be had. The rattle of the tommy-gun vied with the Charleston as the sound of the 20s.

Those opposed to the ban began to gather strength on the back of a crime wave of gang murders. They pointed out that gangsters were pocketing revenues that could have helped communities. They said that conservative rural America was imposing its values on an unwilling urban population that saw things differently.

Prohibition was repealed when America needed revenues in the wake of the Great Depression, and when America needed some comfort from its woes. Looking back, it seemed like a self-inflicted nightmare. The prohibition of recreational narcotics has produced its own subculture of criminal gangs, and of large-scale turf war murders. Like booze, the ban faces a significant section of the population prepared to trade the risks for the pleasures. As state after state and country after country moves to legalize, it looks very much as if the hard lessons of prohibition are slowly being relearned.

To be nakedly ideological about utilities nationalisation

The country cousins over at the IFS are apparently being “nakedly ideological” when they question whether the re-nationalisation of the utilities will contribute to beating climate change. As is well known we’re rather less worried about that change problem, thinking it at worst a chronic problem that will be solved over time, but we can still be nakedly ideological ourselves on this more specific point.

Labour’s plan to renationalise large chunks of the economy risks years of disruption that could delay Britain’s transition to a low-carbon economy, a thinktank has said.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies warned that taking water, energy companies, the Royal Mail and railways under state control would be costly, complex and risky and said Labour might do better to tighten regulation instead.

Lucy Kraftman, an IFS research economist, said: “The industries that Labour plan to nationalise are vital to the UK economy. The key question is whether they would be better managed in the public sector, and what nationalisation can achieve that changing the current regulatory frameworks cannot.

....

The shadow chancellor John McDonnell flatly rejected the IFS argument.

“Labour’s proposals for nationalisation will enable us to speed up the transition to a sustainable economy and enable us to meet our decarbonisation targets all the sooner,” he said.

It’s not exactly obvious that McDonnell is right here. We, nakedly ideological as we are, have difficulty in believing that political and bureaucratic management is going to be more efficient that profit seeking and capitalist. But putting that aside, why not remind ourselves why we did privatise the, say, water companies?

Because the system needed upgrading for environmental reasons - the EU was insisting - and government wouldn’t come up with the money. Therefore it was sold off to the capitalists who did put the billions in. Largely, it is true, by not wasting the current revenues on the politically insisted upon while politically run vast and unnecessary workforces.

That is, greater operational efficiency paid for the environmental upgrade.

We’d also be interested to see how a centralised CEGB would have allowed in all those small scale and privately funded wind farms, solar panels and all the rest.

Or, as we might put it, given that one of the reasons for privatisation was to enable meeting the new environmental standards, how will re-nationalisation aid meeting the new environmental standards?

Is it physically possible to plant 100 million trees per year?

Labour’s eye-catching promise to plant two billion trees by 2040 is not particularly believable.

All the major political parties have pledged to plant millions of trees as part of a larger ‘green’ strategy. The Conservatives have committed to 30 million trees a year until 2024, while the Liberal Democrats want 60 million a year until 2045. Labour’s plans add up to 100 million a year. While this all sounds like a valiant cause and one that may be applauded by some, this forestry arms race raises more problems than it solves.

Let’s start with the logistics: planting two billion trees by 2040 amounts to 270,000 trees per day or 190 trees per minute, 24 hours a day for 20 years. This is certainly a large number, and it gets even more difficult when you realize that you cannot plant year round. The planting season is more like four or, at a stretch, six months. In the best case scenario of a six month planting season they would have to plant 500,000 trees per day.

The infrastructure required for this project is phenomenal. Will the trees be planted by hand, which is incredibly labour intensive, or by mechanical means, which brings extra costs and potentially negative environmental impacts?

Either way, it would require a large temporary workforce for this specific purpose. This raises questions such as what will these workers do in the non-planting months? Where are they coming from? UK unemployment stands at just 3.8%. It is unlikely many of those will be capable and willing to do the job.

Where will the seedlings come from? The state of North Carolina produces 15 million seedlings in their nurseries each year. North Carolina, which is approximately half the size of the UK, is a very heavily forested state and depends on its forestry output as a large portion of the economy. Their infrastructure has been built up over the years for specifically this purpose. Does anyone believe they could increase their production between six and seven times overnight?

In order to grow 100 million seedlings per year you will need approximately 3,300 acres of greenhouses/nurseries. Assuming there is enough supply and infrastructure to get the 100 million seedlings each year (even more when you consider the mortality rate), where are they going to be planted? Assuming a planting density of 500 trees per acre, you’ll need over 300 square miles each year or 6,250 square miles in the next 20 years. This is equivalent to almost 7% of the UK landmass.

And now for the science: a critical factor to look at are the species of trees, the plan for the forests, and the long-term environmental impacts.

Planting 190 trees a minute for 20 years gets us to two billion more trees, but only if all of the trees survive. This is unlikely. The normal two-year survival rate of trees is 80%. This reduces the actual number of new trees, only to be further reduced as more trees die before reaching maturity and peak growing years.

They will also need to consider what type of trees are going to be grown and planted. Evergreens such as pine, spruce and firs are easier to grow and plant but a more diversified forest that includes hardwoods such as oaks and maples would be better for wildlife, national parks, and the overall health of the forests. A homogeneous forest is much more susceptible to disease, insects and other environmental dangers.

Let’s also hope there are no forest fires in these areas for the next 20 years: every forest fire is — in a sense — a double penalty on the CO2 emission scale.The fire kills the trees and stops them from absorbing future CO2 while at the same time releasing the stored up CO2 in the trees as they are burned.

So given all those considerations, will planting billions of trees help the UK become carbon neutral? Two billion trees will take care of 47 million tonnes of CO2 per year but this is a gross number. There will be emissions involved in getting the trees to their stage in life when they can actually “clean” CO2 from the atmosphere. And don’t forget the amount of CO2 that will be put into the atmosphere from building and maintaining nurseries, heating and cooling the greenhouses, fertilizing the seedlings, transporting them to the planting sites and planting itself — especially if using mechanical means which may be required in order to physically plant this volume of trees.

If something sounds too good to be true it usually is — this is especially so when a politician says it, doubly so during an election.

Richard Schondelmeier has a Bachelor of Science in Forestry and a Masters of Science in Forest Resource Management from the University of New Hampshire

When a killer smog hit London

It began late on December 4th, 1952, and lasted about a week. It was London’s Great Smog, a name that derived from the combination of smoke and fog. Unusually cold weather coupled with an anticyclone and windless conditions created a pall of airborne pollutants that gripped the UK’s capital city for days.

Virtually all of London’s several million homes were heated by coal fires, and the coal used was a low-grade, high sulphur variety, since the higher grade ‘hard’ coals such as anthracite were mostly exported. To the smoke from domestic fires was added that of coal-fired power stations, such as those in Battersea, Bankside, Fulham, Greenwich and Kingston upon Thames.

The UK’s meteorological office estimated that there were emitted each day of the Great Smog some 1,000 tonnes of smoke particles, 140 tonnes of hydrochloric acid, 14 tonnes of fluorine compounds, and 370 tonnes of sulphur dioxide which may have been converted to 800 tonnes of sulphuric acid. In other words, it was a very sooty and acidic cloud that enveloped London for several days. It was also the worst air pollution event in UK history.

It reduced visibility, in some cases to a few feet. People groped their way along hedges to find their homes. The combination of sulphurous chemicals and tarry soot particles gave the smog its yellow-black colour, like pea soup. Londoners called it a ‘pea-souper.’ Vehicular traffic virtually stopped, except for the London Underground. Ambulances could not run. Theatres and cinemas closed because audiences could not see the stage or the screen. Sports events, indoors and outdoors, were cancelled. It saw the appearance of the new white ‘smog masks’ on people’s faces.

There were deaths resulting from various lung diseases, including several forms of bronchitis and other respiratory tract infections. Estimates at the time suggested 6,000 deaths, but research afterwards, including those who died in the weeks and months following as a result, put the figure at 12,000 dead and over 100,000 suffering related illnesses.

The Great Smog raised public awareness of the poor quality of London’s air and that of other cities, and led to the passing of the 1956 Clean Air Act which restricted emissions, and ultimately banned coal burning in cities. From the late 1970s a clean-up took place across a London whose buildings, including Parliament and Westminster Abbey, were jet-black from centuries of soot-laden smoke. London’s blackened buildings were systematically spray cleaned to reveal the red brick and honey-coloured stone that characterize them today.

A problem was identified, and measures were taken to redress it. Similar action was taken with the River Thames, then biologically dead but now, after regulations were put into effect, teeming with life again. The same is being done with the UK’s emissions. Coal is rapidly being phased out, with oil to follow. Much cleaner gas is being used as a stop-gap until wind, solar and other renewables can supply our power, and electricity can drive our vehicles. Despite somewhat hysterical talk of the coming extinction of humankind, the problem is being addressed and solved, just as the problem of the London smog was solved.

The Singapore on Thames question - Do you sincerely want to be rich?

Quoting Bernie Cornfeld might not be entirely appropriate for a free market think tank as much of his activity was over the edge of what even we think a free market should allow. And yet it is the correct question to be asking about this idea of Singapore on Thames:

If he wants working-class Labour votes the PM can’t promote the rightwing post-Brexit ideal of Singapore-on-Thames

Singapore’s GDP per capita, at PPP exchange rates, is some $57,700. That for the UK is some $39,700. for the avoidance of doubt here, PPP means we’ve already taken account of differences in the cost of things across geography. We’d rather like a near 50% uplift in our real standard of living. We’re pretty sure that most of the country, including those of the working class who generally vote Labour, would like a 50% uplift in their real standard of living. Actually, the only person we know of who thinks that a higher standard of living is a bad idea is Caroline Lucas.

So, the actual question to ask about the Singapore on Thames idea is “Do you sincerely want to be rich?” If the answer is yes then let’s get on with it, shall we? Just this time in a legal manner. As, obviously, Singapore has done.

Having sniped at The Guardian’s subeditors - they are responsible for sub-headers after all - there’s also a little point to have out with the paper’s Economics Editor, Larry Elliott.

Nor is it the case that there has been no state aid for the financial sector, just that it has been delivered in a less overt way. The Docklands Light Railway and the Jubilee line extension that link Canary Wharf to central London are either infrastructure projects or state aid, depending on your point of view.

Not really Larry, no. As your own newspaper has reported the Jubilee Line extension to Canary Wharf was funded by the landlords of Canary Wharf. As the Crossrail station there was also so funded. As the developers of Battersea power station into luxury flats also funded Battersea tube station. As, in fact, Hong Kong funds its entire metro system, from the land value uplift around the stations.

Hong Kong is, we agree, a different place from Singapore yet there really are things we can learn - even apply having learnt them - from these richer places out there in Asia. Like, you know, how to get richer?

ASI Forum will change your life — sign up before it's too late

This is important!

Saturday, December 7th will not only change your life. It will change the world.

That is when the people who will shape tomorrow’s world, including yourself, will see a glimpse of the future.

That's because Saturday is the ASI’s Forum at The Comedy Store in London, where we will explore the ideas for a better future.

A world in which young people are well educated so they can achieve success. Flying cars make traffic jams as obsolete as the smog they generated. Young people can afford houses they want to live in.

Is this some Corbynist fantasy funded by money grown on trees? No!

It is the reality already happening if only more people had eyes to see it.

On Saturday you can.

Watch how a single tax trick boosts our wealth, how vigilance today will banish the would-be surveillance state, and learn how to penetrate the fake statistics to see the world as it really can be.

They say the best things in life are free. Forum is one of the bestest of the best and it isn’t. But where else can you put the future in the palm of your hand from just £5?

There are still some places, but only if you sign up NOW.

Don’t just sit there.

Do it!

What?

A day of talks from leading thinkers on the underappreciated ideas that explain and could help imrpove the world around us.

Who?

Anthony Breach (Analyst, Centre for Cities) on ‘Homes on the Right Track – How Green Belt reform can solve the housing crisis and save our environment’

Sam Bowman (Principal at Fingleton Associates and Senior Fellow at the Adam Smith Institute) on 'The Most Important Tax Cut You’ve Never Heard Of'

Sophie Sandor (Documentary filmmaker) on ‘Education and The State’

...and many many more.

Where?

The Comedy Store, 1a Oxendon St, London SW1Y 4EE

The nearest tube station is Piccadilly Circus (Piccadilly and Bakerloo Lines)

When?

9.30am for 10:00am to 5.00pm, Saturday December 7th 2019

The arrival of the potato

Thomas Herriot, an astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator, is credited with first introducing the potato into England from Colombia in South America on December 3rd, 1586. It was a fateful event.

The potato was a richer food source than grain. This was because grain stalks would collapse if the head were too heavy, whereas potatoes, grown underground, had no such limits. Not until Norman Borlaug developed short-stemmed grains in his Green Revolution, could cereal crops compete.

Farmers had previously had to leave half their fields fallow to allow the soil to replenish itself, but now they could grow potatoes on the fallow land. The result was an effective doubling of Europe’s food supply. The norm had been that city dwellers could survive lean times by having the wealth and facilities to store grains, but rural dwellers lived constantly on the edge of starvation. Now the potato gave them a calorie source that provided a cushion.

The Europeans copied the South American habit of growing potatoes on relatively poor soil enriched by guano as fertilizer. Guano was imported in bulk as the world’s first intensive fertilizer, and launched the fertilizer industry. When the Colorado beetle also entered Europe to prey on the potato crops, farmers discovered that a form of arsenic (originally found in green paint) was effective against them. Suppliers competed to develop ever more potent arsenic blends, and began the modern pesticide industry

Not everyone took to the potato. The Enlightenment philosopher Diderot was less than enthusiastic in his Encyclopedia. He wrote: “No matter how you prepare it, the root is tasteless and starchy. It cannot be regarded as an enjoyable food, but it provides abundant, reasonably healthy food for men who want nothing but sustenance.”

A problem was building, however, in the widespread reliance on a single crop that lacked genetic variety. The South Americans used many different variants, but the Europeans did not. Theirs was a monoculture vulnerable to pests and parasites. Ireland was particularly exposed because the high caloric yield of the potato had enabled land to be split into smaller parcels of land, each of which could just support a family on potatoes. About 40 percent of the Irish ate no other solid food. The same was true of 10-30 percent of people across a huge swathe of Europe stretching from Ireland to the Urals in Russia.

Disaster struck in the middle of the 19th Century with the appearance of Phytophthora infestans, or Potato Blight. It wiped out up to half the crop in Europe, devastating Ireland the most. A million or more died there of starvation, and two million more migrated, mostly to the United States. This represented a loss of a third or more of the population, which never recovered. Ireland today is the only European country with a population smaller than it had 150 years ago.

The lesson has been noted, and although today there are monocultures in some crops like grains and bananas, where the most successful strains are widely cultivated, other varieties are kept in reserve, ready to be deployed if the dominant strain becomes vulnerable to pests.

The potato brought sustenance that ended the recurrent famines that had plagued Europe, but it taught a lesson about avoiding reliance on a single strain of a single crop. Europeans learned that lesson the hard way.

If only the Fair Tax Mark knew what they were talking about

The Fair Tax Mark wants to tell us all that the Silicon Valley giants aren’t paying enough in tax. Their analysis rather failing on two technical points which they, as self-declared experts in taxation, should really know about. Plus, obviously, the economic point that we value organisations producing things for the value we place upon their production - defined as our value in the consumption of them - not how much tax they pay.

That last will obviously not penetrate their tutti nello stato mindset but the two technical points do still invalidate their analysis:

The big six US tech firms have been accused of “aggressively avoiding” $100bn (£75bn) of global tax over the past decade.

Amazon, Facebook, Google, Netflix, Apple and Microsoft have been named in a report by tax transparency campaign group Fair Tax Mark as avoiding tax by shifting revenue and profits through tax havens or low-tax countries, and for also delaying the payment of taxes they do incur.

The first technical point is that the thing being complained about has already been solved. By President Trump in fact. There was an oddity in US corporate tax law - foreign profits were only taxed in the US if they actually came onshore in the US. Thus, if by some clever book-keeping, profits could be parked outside the US and yet tax free from other jurisdictions no taxes would be charged. This didn’t do much good in the long run as such profits could not, cannot, be paid out to shareholders without coming onshore and thus being taxed. But that is what was being done and some $2 trillion - the figure varying dependent on who was asked to do the totting up - was stashed on varied Caribbean islands.

We’re all in favour of this of course but the law has already been changed. Part of the Trump tax changes was that, repatriated or not, those profits are subject to US taxation. There are no pots of entirely untaxed corporate profits any more. The problem being complained of has been solved, by a Republican to boot.

The second technical point is that they’re doing their counting wrong. Something of a distinct problem for people attempting to do that beancounting.

The report finds that there is a significant difference between the cash taxes paid and both the expected headline rate of tax and, more significantly, the reported current tax provisions.

You cannot - usefully at least - compare cash taxes paid with expected taxation because corporation tax is due in arrears. The amount of tax for the financial year 2016 is actually due in the financial year 2017 and so on. When companies are growing fast, something we’d agree the SV Six tend to do, this means that there always will be a low tax rate for we’d be comparing tax paid for 2016 with tax due for 2017, that latter being a much larger sum. It’s even possible to test this. When the profits stutter - as has happened to at least one of the companies - then the tax rate rises substantially as the tax payment for the earlier, more profitable, year is handed over in one where the tax due at headline rates falls.

It’s entirely true that we disagree with the Fair Tax Mark on everything, including the cuteness or not of kittens. But we do think it would be helpful if they were aware of the details of the subject under discussion and, just possibly, were able to count properly.

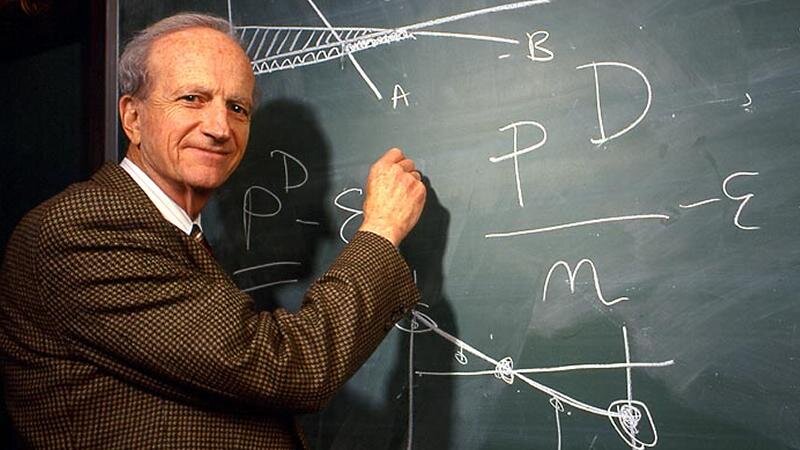

Gary Becker

On December 2nd, 1930, Gary Becker was born. One of the most influential economists of his day, he received the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1992. Much of his influence came about because he used the methods of economics to analyze human behaviour for the first time in areas such as family life, crime and sociology. As a professor of Economics and Sociology at Chicago, he was among the leaders of the so-called third generation of the Chicago School.

In his “The Economics of Discrimination” (1957) he studied racial discrimination in employment, finding that employers who discriminate against minorities deny themselves access to low-wage labour and thus raise their costs and lower their profits. Employers who do not discriminate against minorities, on the other hand, increase their productivity.

His work on crime as equally trail-blazing. He examined how criminals assess rationally how far their likely gains might be offset by the possible costs of being caught and punished. In fact, criminals make economic calculations that can be altered if the chances of apprehension are increased, or the penalties suffered in consequence are raised.

Becker was one of the early and leading exponents of the notion of human capital. Milton Friedman described him as “the greatest social scientist who has lived and worked in the second part of the twentieth century.” Investing in a person’s education and training was similar, Becker said, to investing in new plant and machinery. It was something that, properly done, could be expected to bring returns.

He applied economic analysis to family activities, looking at their division of labour, the allocation of parental time to children, and the steps they gook to maximize preferences. He treated the household as if it were a business engaged in the production of meals, shelter and childcare. His work took economics deep into sociology and anthropology.

We knew him through the Mont Pelerin Society, where he served as its President from 1990-92, and found him always courteous and ready to discuss his ideas, especially with the young people attending its conferences as guests. In addition to his Nobel Prize, he was also awarded in 2007 America’s highest civilian honour, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

He was a leader among the scholars who took economics out of its abstract academic towers and into the real world of homes and families, and into prisons and crime gangs. In doing so, he and his colleagues had a positive impact on the disciplines they entered, fields such as sociology, criminology, and demography, as well as on economics itself.