Is Spain's Constitution outdated?

Today being the Spanish Day of the Constitution, it is an apt time to reflect on said Constitution and its commitment to democracy. While it may have worked in 1978, Spain ought to amend its constitution to be truly democratic, especially with regards to the question of Catalan independence.

On 14th October, nine of Catalonia’s independence leaders were jailed for a total of over 100 years but what Madrid seemingly fails to realise time and time again is that imprisoning their leaders doesn’t address the complaints of angry Catalan nationalists— and may exacerbate the issue. Support for independence and anti-Spanish rhetoric is still prominent both within Catalonia and internationally.

Catalonia’s now infamous 2017 independence referendum was allowed under the Law on Referendum on Self-determination of Catalonia passed by the Parliament of Catalonia. It was not, however, permissible under the Spanish constitution. And so, Spain’s national government enacted Article 155 which allowed them to use ‘necessary measures’ to force Catalonia to comply with the idea of ‘the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation’. Madrid’s idea of ‘necessary measures’ included dissolving parliament, and police brutality, actions that would ultimately add fuel to the (now literal) fire(s).

Whether or not the referendum should have gone ahead, Madrid’s response of clamping down on Catalonia so harshly is telling of how desperate they are. Prohibiting the referendum today seems just as anachronistic as Spain declaring war in Catalonia back, in 1934. It seems that the government strategy has changed little since. The ban on Spain’s autonomous regions gaining independence was written in the constitution after the Franco dictatorship in order to keep Spain unified while it regained its feet. Madrid shouldn’t cling to this outdated system. By amending the constitution, Spain may seem less fragile and tension will likely be eased. Indeed the reforms are a step in the right direction.

The neoliberal standpoint is that liberty is of utmost importance and as such, the legitimacy of state ought to depend on its people. If the majority of Catalans withhold their consent to being part of Spain, then the region should be able to leave Spain.

Allowing a real vote does not mean that Spain will automatically lose Catalonia. It is important to remember that the result of the 2017 referendum should not be viewed as gospel. The referendum was not verified and there are claims that some people voted twice. Furthermore, it is likely that those who would have voted against independence would have also wanted to obey central government and not legitimise referendum by voting in it. This suggests that were Spain to hold a legitimate referendum it is possible that the outcome would be less overwhelmingly pro independence. While 90% of votes being in favour of independence may seem pretty conclusive, it was 90% of 43% of the population. When discussing Catalonia, the debate shouldn’t simply be pro independence or anti independence, but rather pro choice or anti choice. Catalonia should only have independence if the majority of Catalans do genuinely support it.

Allowing a real vote would, however, allow Spain to gauge the Catalan people’s level of discontent with the rest of Spain. It allows discussions to go ahead to de-escalate the situation, knowing whether independence truly is the desired outcome from the majority of the Catalan people.

If Spain were to ever allow its autonomous regions independence, then a key detail that should be ironed out is whether or not any final negotiations must be voted on. As we have seen with Brexit, there are calls for a ‘people’s vote’ on any possible withdrawal agreement. This ambiguity can be avoided by making it clear whether it is the government or the citizens that have the final say in any agreements.

The issues arising in Catalonia could stem from the inflexibility of a written constitution. When discussing Catalonia, comparisons with Scotland seem natural, however, Spain and the United Kingdom are very different countries. First of all, it is not illegal in Britain for different regions to secede from the union. The question of a Scottish independence referendum was not as outlandish. Another key difference between the two countries, is that Spain, unlike the UK, has a written constitution. Having a written constitution makes Spain inflexible and forced into upholding principles that may now seem archaic. Spain has had its current constitution since 1978 which may not sound like a long time, but Spain has changed a lot since then. In 1978, Spain had transitioned from a dictatorship that spanned five decades to a fledgling democracy. Now, it is a democratic country (or at least it is well on its way to being one). Any efforts to update the constitution will undergo much scrutiny and debate, making Spain a cumbersome nation and making it harder to adapt and keep up with the modern world.

The question should not be whether or not you support an independent Catalonia but if you support democracy. For those who do support democracy, the way of achieving it is clear: in the spirit of liberty, reform the constitution and have a real vote.

The ruin of Venezuela

Venezuela’s collapse from one of Latin America’s richest countries to one of its poorest began on December 6th, 1998, with the election of Hugo Chavez as its President. Chavez had imbibed Marxist communism as a teenager, and was affected by the FALM communist insurgency in Venezuela, one supported by Cuban leader Fidel Castro. He was by no means a Marxist intellectual, enrolling in the Military Academy to receive expert baseball coaching, but lacked talent, and was remembered as a barely adequate student who graduated near the bottom of his class.

With fellow officers, he took part in a failed coup in 1992, but established a popular leftwing political party and won the presidency in 1998 with 56 percent of the vote, having persuaded the country’s outsiders and impoverished groups to unite behind his banner in opposition to the established parties.

When he started to rule increasingly by decree, taking Venezuela down the path that Cuba had followed, it provoked a general strike, at the centre of which was the state oil company that earned 80 percent of the country’s export revenue. Chavez broke the strike by firing half its workforce and replacing them with his cronies who had no expertise in the oil business.

The price of oil was rising, however, bringing in revenues that Chavez began spending on lavish social programmes. His economy became dangerously dependent on a single commodity, and had not built up any kind of reserve to cope with a fall in oil prices.

When oil prices did fall, the government printed extra money to cover the shortfall, and when inflation inevitably followed, it fixed prices by law, causing shortages of basics such as sugar, milk and beans. Prices rocketed for food, water, medical supplies and household goods. A package of constitutional changes, passed by a referendum in 2009 cleared the way for Chavez’s perpetual reelection, which he responded to by cracking down on opponents, stifling a free press, and shutting down the one independent TV channel that was in opposition.

Fake government statistics concealed a high infant mortality rate and increasing malnutrition. When Chavez died of cancer in 2013, he was succeeded by his chosen nominee, Nicolas Maduro, who continued his policies and led Venezuela down the ever-closing spiral to poverty and degradation. Inflation exceeded 80,000 percent, and the poverty rate reached 90 percent. Millions emigrated. The country relapsed into authoritarianism as its economy collapsed.

It was, alas, a familiar story, seen before in other countries that followed the same failed policies. Adam Smith observed that:

“Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice.”

Poor Venezuela had none of these, and went from comparative affluence to utter squalor and poverty. A country can do many things wrong, yet still thrive if it has fairly free markets and fairly light taxes. There are three things, however, that it cannot do if it is to prosper: genocide, civil war and socialism.

Yes, of course governments should target happiness

It’s an odd question even for people to ask, whether governments should target happiness or GDP. The answer is so obvious that why even bother to ponder it, happiness is the point:

Is the relentless reach for economic growth coming at the expense of our personal happiness and well-being?

It is a question that is being asked around the world and has even inspired part of the Liberal Democrat manifesto. It has proposed a "well-being budget" that would base decisions on factors in addition to growth, an idea borrowed from New Zealand.

Iceland’s Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir also revealed on Tuesday that her country will be the latest to focus on well-being over gross domestic product (GDP).

“An Icelandic poet actually said famously that having sex with your wife does not count in GDP but having sex with a prostitute does so that should really make us think,” she joked...

The answer to that little conundrum being that the roughly 2 to 3% of men who regularly use prostitutes (a reasonable estimate, lifetime incidence is usually measured at around 10%) find that their happiness is so enhanced, the other 97% do not. Which is that vital clue to what the pursuit or targeting of happiness should actually be about.

As economists keep pointing out, utility - not the same as happiness itself but the jargon for something similar - is an entirely personal thing. There are, after all, those who appreciate Simon Cowell. To target happiness is thus to be allowing the maximal freedom to all to maximise their own utility.

That is, happiness maximisation means the classically liberal state where intervention is only allowed, let alone justified, when the pursuit limits the ability of another to so pursue.

We having an nice little example of this too:

Almost every worker in the country is happy with the terms of their employment, despite the rise of "gig" work and a long-running row over zero-hours contracts.

Around 99pc of workers across Britain are satisfied with their contract according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), with very minor variations depending on the type of employment. For example, this falls to 97pc for men in part-time jobs.

It is further evidence that the common opinion that zero-hours agreements are rampant and unpopular is false. The contracts offer flexibility to around 900,000 workers and their employers, but have become the focus of much political criticism in recent years.

Leave people alone to get on with things as they’ll pursue their own happiness as well as is possible within the constraints of physical reality. At which point, well, job done, isn’t it?

That is, the secret to the political maximisation of happiness is that politics and politicians potter off and do something else - preferably nothing - other than defend the rights of the citizenry to the pursuit of happiness and leave the rest of us to the delights of chacun a son gout.

That this is also the method of GDP maximisation is just a happy circumstance.

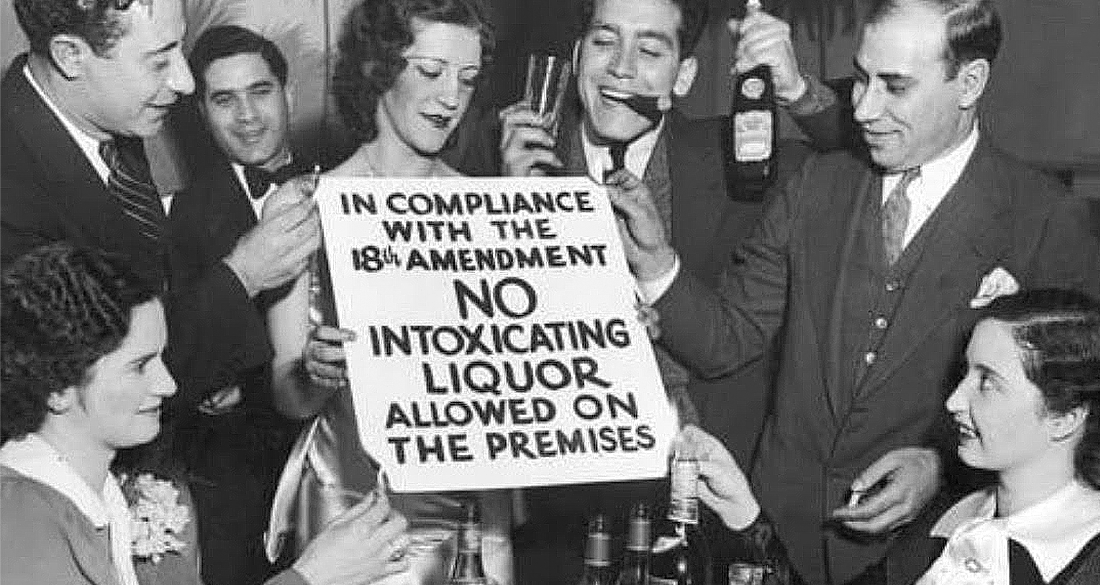

The end of Prohibition

America went dry on January 17th, 1920, as the Eighteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution, inaugurating Prohibition. Just under 14 years later, on December 5th, 1933, the Twenty-First Amendment was added to the Constitution, repealing the Eighteenth and ending the era of Prohibition.

Prohibition was a disaster, in that it was an attempt to force the views of some, led by pious protestants and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, upon the whole of America. The Anti-Saloon League was opposed by many Catholics and German Lutherans, but German Americans had lost prestige during the First World War, and were unable to prevent the victory of the “drys.”

Criminal gangs were prepared to supply illicitly what the government had made illegal, and soon dominated the illegal supply of beer and spirits in most US cities. Booze was smuggled across borders and made domestically. A week after prohibition came in, small portable stills went on sale throughout America. Crates of liquor were smuggled in from Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean.

Doctors lobbied to be allowed to prescribe alcohol for “medicinal” purposes, and between 1921 and 1930, they earned roughly $40 million from whiskey prescriptions. BY 1926 the number of illegal “speakeasy” drinking establishments was put at between 30,000 to 100,000 in New York City alone. Cheap bathtub hooch had its raw quality concealed by a fashionable taste for cocktails, and just as government poisoned industrial alcohol to prevent its use for drinking, so gangs employed chemists to reverse the process and make it harmless.

Britain’s visiting Prince of Wales came back from Canada reporting a song he’d learned there:

Four and twenty Yankees, feeling very dry,

Went across the border to get a drink of rye.

When the rye was opened, the Yanks began to sing,

"God bless America, but God save the King!"

Prohibition made a mockery of the law and set ordinary Americans against the police and the law. Gangsters made huge sums from bootlegging, and bought judges and entire police departments. Al Capone was cheered at baseball games as a hero who gave people what they wanted. Gang slaughter came in as rivals killed each other in territorial fights for the vast profits to be had. The rattle of the tommy-gun vied with the Charleston as the sound of the 20s.

Those opposed to the ban began to gather strength on the back of a crime wave of gang murders. They pointed out that gangsters were pocketing revenues that could have helped communities. They said that conservative rural America was imposing its values on an unwilling urban population that saw things differently.

Prohibition was repealed when America needed revenues in the wake of the Great Depression, and when America needed some comfort from its woes. Looking back, it seemed like a self-inflicted nightmare. The prohibition of recreational narcotics has produced its own subculture of criminal gangs, and of large-scale turf war murders. Like booze, the ban faces a significant section of the population prepared to trade the risks for the pleasures. As state after state and country after country moves to legalize, it looks very much as if the hard lessons of prohibition are slowly being relearned.

To be nakedly ideological about utilities nationalisation

The country cousins over at the IFS are apparently being “nakedly ideological” when they question whether the re-nationalisation of the utilities will contribute to beating climate change. As is well known we’re rather less worried about that change problem, thinking it at worst a chronic problem that will be solved over time, but we can still be nakedly ideological ourselves on this more specific point.

Labour’s plan to renationalise large chunks of the economy risks years of disruption that could delay Britain’s transition to a low-carbon economy, a thinktank has said.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies warned that taking water, energy companies, the Royal Mail and railways under state control would be costly, complex and risky and said Labour might do better to tighten regulation instead.

Lucy Kraftman, an IFS research economist, said: “The industries that Labour plan to nationalise are vital to the UK economy. The key question is whether they would be better managed in the public sector, and what nationalisation can achieve that changing the current regulatory frameworks cannot.

....

The shadow chancellor John McDonnell flatly rejected the IFS argument.

“Labour’s proposals for nationalisation will enable us to speed up the transition to a sustainable economy and enable us to meet our decarbonisation targets all the sooner,” he said.

It’s not exactly obvious that McDonnell is right here. We, nakedly ideological as we are, have difficulty in believing that political and bureaucratic management is going to be more efficient that profit seeking and capitalist. But putting that aside, why not remind ourselves why we did privatise the, say, water companies?

Because the system needed upgrading for environmental reasons - the EU was insisting - and government wouldn’t come up with the money. Therefore it was sold off to the capitalists who did put the billions in. Largely, it is true, by not wasting the current revenues on the politically insisted upon while politically run vast and unnecessary workforces.

That is, greater operational efficiency paid for the environmental upgrade.

We’d also be interested to see how a centralised CEGB would have allowed in all those small scale and privately funded wind farms, solar panels and all the rest.

Or, as we might put it, given that one of the reasons for privatisation was to enable meeting the new environmental standards, how will re-nationalisation aid meeting the new environmental standards?

Is it physically possible to plant 100 million trees per year?

Labour’s eye-catching promise to plant two billion trees by 2040 is not particularly believable.

All the major political parties have pledged to plant millions of trees as part of a larger ‘green’ strategy. The Conservatives have committed to 30 million trees a year until 2024, while the Liberal Democrats want 60 million a year until 2045. Labour’s plans add up to 100 million a year. While this all sounds like a valiant cause and one that may be applauded by some, this forestry arms race raises more problems than it solves.

Let’s start with the logistics: planting two billion trees by 2040 amounts to 270,000 trees per day or 190 trees per minute, 24 hours a day for 20 years. This is certainly a large number, and it gets even more difficult when you realize that you cannot plant year round. The planting season is more like four or, at a stretch, six months. In the best case scenario of a six month planting season they would have to plant 500,000 trees per day.

The infrastructure required for this project is phenomenal. Will the trees be planted by hand, which is incredibly labour intensive, or by mechanical means, which brings extra costs and potentially negative environmental impacts?

Either way, it would require a large temporary workforce for this specific purpose. This raises questions such as what will these workers do in the non-planting months? Where are they coming from? UK unemployment stands at just 3.8%. It is unlikely many of those will be capable and willing to do the job.

Where will the seedlings come from? The state of North Carolina produces 15 million seedlings in their nurseries each year. North Carolina, which is approximately half the size of the UK, is a very heavily forested state and depends on its forestry output as a large portion of the economy. Their infrastructure has been built up over the years for specifically this purpose. Does anyone believe they could increase their production between six and seven times overnight?

In order to grow 100 million seedlings per year you will need approximately 3,300 acres of greenhouses/nurseries. Assuming there is enough supply and infrastructure to get the 100 million seedlings each year (even more when you consider the mortality rate), where are they going to be planted? Assuming a planting density of 500 trees per acre, you’ll need over 300 square miles each year or 6,250 square miles in the next 20 years. This is equivalent to almost 7% of the UK landmass.

And now for the science: a critical factor to look at are the species of trees, the plan for the forests, and the long-term environmental impacts.

Planting 190 trees a minute for 20 years gets us to two billion more trees, but only if all of the trees survive. This is unlikely. The normal two-year survival rate of trees is 80%. This reduces the actual number of new trees, only to be further reduced as more trees die before reaching maturity and peak growing years.

They will also need to consider what type of trees are going to be grown and planted. Evergreens such as pine, spruce and firs are easier to grow and plant but a more diversified forest that includes hardwoods such as oaks and maples would be better for wildlife, national parks, and the overall health of the forests. A homogeneous forest is much more susceptible to disease, insects and other environmental dangers.

Let’s also hope there are no forest fires in these areas for the next 20 years: every forest fire is — in a sense — a double penalty on the CO2 emission scale.The fire kills the trees and stops them from absorbing future CO2 while at the same time releasing the stored up CO2 in the trees as they are burned.

So given all those considerations, will planting billions of trees help the UK become carbon neutral? Two billion trees will take care of 47 million tonnes of CO2 per year but this is a gross number. There will be emissions involved in getting the trees to their stage in life when they can actually “clean” CO2 from the atmosphere. And don’t forget the amount of CO2 that will be put into the atmosphere from building and maintaining nurseries, heating and cooling the greenhouses, fertilizing the seedlings, transporting them to the planting sites and planting itself — especially if using mechanical means which may be required in order to physically plant this volume of trees.

If something sounds too good to be true it usually is — this is especially so when a politician says it, doubly so during an election.

Richard Schondelmeier has a Bachelor of Science in Forestry and a Masters of Science in Forest Resource Management from the University of New Hampshire

When a killer smog hit London

It began late on December 4th, 1952, and lasted about a week. It was London’s Great Smog, a name that derived from the combination of smoke and fog. Unusually cold weather coupled with an anticyclone and windless conditions created a pall of airborne pollutants that gripped the UK’s capital city for days.

Virtually all of London’s several million homes were heated by coal fires, and the coal used was a low-grade, high sulphur variety, since the higher grade ‘hard’ coals such as anthracite were mostly exported. To the smoke from domestic fires was added that of coal-fired power stations, such as those in Battersea, Bankside, Fulham, Greenwich and Kingston upon Thames.

The UK’s meteorological office estimated that there were emitted each day of the Great Smog some 1,000 tonnes of smoke particles, 140 tonnes of hydrochloric acid, 14 tonnes of fluorine compounds, and 370 tonnes of sulphur dioxide which may have been converted to 800 tonnes of sulphuric acid. In other words, it was a very sooty and acidic cloud that enveloped London for several days. It was also the worst air pollution event in UK history.

It reduced visibility, in some cases to a few feet. People groped their way along hedges to find their homes. The combination of sulphurous chemicals and tarry soot particles gave the smog its yellow-black colour, like pea soup. Londoners called it a ‘pea-souper.’ Vehicular traffic virtually stopped, except for the London Underground. Ambulances could not run. Theatres and cinemas closed because audiences could not see the stage or the screen. Sports events, indoors and outdoors, were cancelled. It saw the appearance of the new white ‘smog masks’ on people’s faces.

There were deaths resulting from various lung diseases, including several forms of bronchitis and other respiratory tract infections. Estimates at the time suggested 6,000 deaths, but research afterwards, including those who died in the weeks and months following as a result, put the figure at 12,000 dead and over 100,000 suffering related illnesses.

The Great Smog raised public awareness of the poor quality of London’s air and that of other cities, and led to the passing of the 1956 Clean Air Act which restricted emissions, and ultimately banned coal burning in cities. From the late 1970s a clean-up took place across a London whose buildings, including Parliament and Westminster Abbey, were jet-black from centuries of soot-laden smoke. London’s blackened buildings were systematically spray cleaned to reveal the red brick and honey-coloured stone that characterize them today.

A problem was identified, and measures were taken to redress it. Similar action was taken with the River Thames, then biologically dead but now, after regulations were put into effect, teeming with life again. The same is being done with the UK’s emissions. Coal is rapidly being phased out, with oil to follow. Much cleaner gas is being used as a stop-gap until wind, solar and other renewables can supply our power, and electricity can drive our vehicles. Despite somewhat hysterical talk of the coming extinction of humankind, the problem is being addressed and solved, just as the problem of the London smog was solved.

The Singapore on Thames question - Do you sincerely want to be rich?

Quoting Bernie Cornfeld might not be entirely appropriate for a free market think tank as much of his activity was over the edge of what even we think a free market should allow. And yet it is the correct question to be asking about this idea of Singapore on Thames:

If he wants working-class Labour votes the PM can’t promote the rightwing post-Brexit ideal of Singapore-on-Thames

Singapore’s GDP per capita, at PPP exchange rates, is some $57,700. That for the UK is some $39,700. for the avoidance of doubt here, PPP means we’ve already taken account of differences in the cost of things across geography. We’d rather like a near 50% uplift in our real standard of living. We’re pretty sure that most of the country, including those of the working class who generally vote Labour, would like a 50% uplift in their real standard of living. Actually, the only person we know of who thinks that a higher standard of living is a bad idea is Caroline Lucas.

So, the actual question to ask about the Singapore on Thames idea is “Do you sincerely want to be rich?” If the answer is yes then let’s get on with it, shall we? Just this time in a legal manner. As, obviously, Singapore has done.

Having sniped at The Guardian’s subeditors - they are responsible for sub-headers after all - there’s also a little point to have out with the paper’s Economics Editor, Larry Elliott.

Nor is it the case that there has been no state aid for the financial sector, just that it has been delivered in a less overt way. The Docklands Light Railway and the Jubilee line extension that link Canary Wharf to central London are either infrastructure projects or state aid, depending on your point of view.

Not really Larry, no. As your own newspaper has reported the Jubilee Line extension to Canary Wharf was funded by the landlords of Canary Wharf. As the Crossrail station there was also so funded. As the developers of Battersea power station into luxury flats also funded Battersea tube station. As, in fact, Hong Kong funds its entire metro system, from the land value uplift around the stations.

Hong Kong is, we agree, a different place from Singapore yet there really are things we can learn - even apply having learnt them - from these richer places out there in Asia. Like, you know, how to get richer?

ASI Forum will change your life — sign up before it's too late

This is important!

Saturday, December 7th will not only change your life. It will change the world.

That is when the people who will shape tomorrow’s world, including yourself, will see a glimpse of the future.

That's because Saturday is the ASI’s Forum at The Comedy Store in London, where we will explore the ideas for a better future.

A world in which young people are well educated so they can achieve success. Flying cars make traffic jams as obsolete as the smog they generated. Young people can afford houses they want to live in.

Is this some Corbynist fantasy funded by money grown on trees? No!

It is the reality already happening if only more people had eyes to see it.

On Saturday you can.

Watch how a single tax trick boosts our wealth, how vigilance today will banish the would-be surveillance state, and learn how to penetrate the fake statistics to see the world as it really can be.

They say the best things in life are free. Forum is one of the bestest of the best and it isn’t. But where else can you put the future in the palm of your hand from just £5?

There are still some places, but only if you sign up NOW.

Don’t just sit there.

Do it!

What?

A day of talks from leading thinkers on the underappreciated ideas that explain and could help imrpove the world around us.

Who?

Anthony Breach (Analyst, Centre for Cities) on ‘Homes on the Right Track – How Green Belt reform can solve the housing crisis and save our environment’

Sam Bowman (Principal at Fingleton Associates and Senior Fellow at the Adam Smith Institute) on 'The Most Important Tax Cut You’ve Never Heard Of'

Sophie Sandor (Documentary filmmaker) on ‘Education and The State’

...and many many more.

Where?

The Comedy Store, 1a Oxendon St, London SW1Y 4EE

The nearest tube station is Piccadilly Circus (Piccadilly and Bakerloo Lines)

When?

9.30am for 10:00am to 5.00pm, Saturday December 7th 2019

The arrival of the potato

Thomas Herriot, an astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator, is credited with first introducing the potato into England from Colombia in South America on December 3rd, 1586. It was a fateful event.

The potato was a richer food source than grain. This was because grain stalks would collapse if the head were too heavy, whereas potatoes, grown underground, had no such limits. Not until Norman Borlaug developed short-stemmed grains in his Green Revolution, could cereal crops compete.

Farmers had previously had to leave half their fields fallow to allow the soil to replenish itself, but now they could grow potatoes on the fallow land. The result was an effective doubling of Europe’s food supply. The norm had been that city dwellers could survive lean times by having the wealth and facilities to store grains, but rural dwellers lived constantly on the edge of starvation. Now the potato gave them a calorie source that provided a cushion.

The Europeans copied the South American habit of growing potatoes on relatively poor soil enriched by guano as fertilizer. Guano was imported in bulk as the world’s first intensive fertilizer, and launched the fertilizer industry. When the Colorado beetle also entered Europe to prey on the potato crops, farmers discovered that a form of arsenic (originally found in green paint) was effective against them. Suppliers competed to develop ever more potent arsenic blends, and began the modern pesticide industry

Not everyone took to the potato. The Enlightenment philosopher Diderot was less than enthusiastic in his Encyclopedia. He wrote: “No matter how you prepare it, the root is tasteless and starchy. It cannot be regarded as an enjoyable food, but it provides abundant, reasonably healthy food for men who want nothing but sustenance.”

A problem was building, however, in the widespread reliance on a single crop that lacked genetic variety. The South Americans used many different variants, but the Europeans did not. Theirs was a monoculture vulnerable to pests and parasites. Ireland was particularly exposed because the high caloric yield of the potato had enabled land to be split into smaller parcels of land, each of which could just support a family on potatoes. About 40 percent of the Irish ate no other solid food. The same was true of 10-30 percent of people across a huge swathe of Europe stretching from Ireland to the Urals in Russia.

Disaster struck in the middle of the 19th Century with the appearance of Phytophthora infestans, or Potato Blight. It wiped out up to half the crop in Europe, devastating Ireland the most. A million or more died there of starvation, and two million more migrated, mostly to the United States. This represented a loss of a third or more of the population, which never recovered. Ireland today is the only European country with a population smaller than it had 150 years ago.

The lesson has been noted, and although today there are monocultures in some crops like grains and bananas, where the most successful strains are widely cultivated, other varieties are kept in reserve, ready to be deployed if the dominant strain becomes vulnerable to pests.

The potato brought sustenance that ended the recurrent famines that had plagued Europe, but it taught a lesson about avoiding reliance on a single strain of a single crop. Europeans learned that lesson the hard way.