Handbags and gladrags

Scientists appear to be able to explain that dancing around handbags and also Saturday Night Fever:

Cha-cha-chimp? Ape study suggests urge to dance is prehuman

Chimpanzees seen clapping, tapping and swaying along to piano rhythms in a music booth

There are certain predelictions among humans that predate there being any humans at all. Much of the modern world being explained by this part of the findings:

Males tended to dance and hoot a lot more than the females. One 39-year-old male, Akira, spent half his time dancing when the piano was playing. Another male, Ayumu, came second in the dance-off, spending about a third of his time jigging about in one way or another. Next was Gon who spent about 10% of his time moving to the sounds.

The females, meanwhile, seemed far less enthusiastic. All danced for less than 10% of the time the music was played. One female, Chloe, had only one move – the “hanging sway”, as the scientists called it – but she apparently preferred not to bother at all.

So, that’s both John Travolta and the collective amble around the pocketbooks observed on dance floors all over the country explained.

This is, however, more important than just an explanation for why we’ve vast barns all over the country in which people can go and indulge in this primordial behaviour. For it is indeed showing that such primordial behaviour does persist. It therefore probably being a good idea to order society in accordance with those base and basic urges, not try to build something for a species that isn’t going to turn up.

Which brings us, of course, to market exchange and that point of Smith’s about the innate urge to truck and barter - this being something that we have also seen in chimpanzees. A non-market society, one which tries to outlaw something so natural, isn’t going to work very well, is it?

At which point a Merry Christmas. For gift giving is voluntary exchange, isn’t it…..

Apollo 8 in lunar orbit

NASA made its bravest move in December 1968. On the very first manned flight of the Saturn V rocket, NASA sent it to the moon. Previous orbital flights had been in low Earth orbit, "like a fly walking on the surface of an apple." Now Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders became the first humans to leave Earth orbit and fly to the Moon. On December 24th, 1968, they entered lunar orbit and became the first humans to orbit another world.

They were also the first humans to see the whole Earth from space, like a blue and white marble, while viewers back on Earth thrilled to the spectacle of their home planet as a small globe in the blackness of space.

The mission was dangerous. They had no lunar module with them, and were totally dependent on the engine of the service module re-starting when required to. They had to burn that engine behind the moon, out of contact with Earth, and it had to burn for 4 minutes and 7 seconds. Too short a burn might have flung them out into space with no hope of return, and too short a burn might have sent them crashing into the moon. The crew said it was the longest four minutes of their lives.

They emerged at exactly the predicted moment, however, in an orbit between 193.3 and 69.5 miles from the lunar surface. Everything they had experienced thus far had been predicted, but something unexpected happened in lunar orbit. They saw the first "Earthrise" as the Earth rose above the lunar horizon, the only coloured object to be seen. This is not generally seen from the lunar surface because the Earth is always in view, but it can be witnessed from lunar orbit.

They made 10 orbits of the moon, and made the famous Christmas Eve live broadcast to Earth with a reading from the Book of Genesis. It was then the most watched TV broadcast ever, seen by an estimated quarter of the world's population either live or delayed. Borman signed off by saying, "And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas and God bless all of you—all of you on the good Earth."

1968 had been a bad year. The Vietnam war was still raging and saw the Tet offensive. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were both assassinated. There were race riots in the US, student riots in Paris, and a riot that marred the Democrat Convention in Chicago. Soviet and Warsaw Pact troops and tanks invaded Czechoslovakia to crush its bid for freedom.

At the close of the year the flight of Apollo 8 lifted morale. On its return, Frank Borman received a telegram from a stranger that simply said, "Thank you Apollo 8. You saved 1968."

The most apt comment was perhaps the observation that the most interesting thing that humans saw when they ventured out into space was their own planet, the one they had left. They saw how fragile it looked, how beautiful, and how tiny it was, lost in the vastness of space. It gave humanity a sense of perspective that has stayed with many of us to this day. Everything that has happened since the first life-forms crawled out of the primaeval sea happened on that tiny blue and white marble spinning in the emptiness of the universe around it.

The Bank of England on house prices: why it's still the supply side, stupid

Are houses expensive in the UK because of inelastic supply, or because of lower interest rates? The answer, according to a new paper from the Bank of England, is both. In this paper’s model, constrained supply and falling real interest rates act like two blades of a scissors. Over the past forty years they have together led to house prices having roughly doubled compared to incomes, while rents have remained at roughly the same share (around 40% of people’s incomes).

The model is similar to the one outlined by Ben Southwood here. To restate what he says, the rental cost of a house (ie, how much it costs to live there for one year) is determined by simple supply and demand. The cost of buying a house is determined by how much people expect it to cost to rent the house for the lifetime of the house – effectively, you’re paying up front for the total lifetime use of the house.

But you could always rent today and invest that money in something else, rather than the house. So what you’re willing to pay today for the total lifetime rental value of the house, and what the current homeowner is willing to accept, depends on the opportunity cost of the money you’d be spending. The “opportunity cost of investment” is what we generally refer to as the “real interest rate” – the average risk-free investment you can make. Lower real interest rates mean the opportunity cost of investing in a house is lower, so people are willing to spend more on doing so.

And as the Bank of England paper shows, this is exactly what has happened in the UK since 1980: as the real interest rate has fallen, the price of houses has risen. And they demonstrate that this has been enough to account for all of the rise in house prices over this period – not immigration, not quantitative easing, and not a change in the restrictiveness of our planning laws.

But this rests on a crucial fact about our housing market: that supply is inelastic, or in other words that higher demand does not lead to higher supply as in the markets for most other things. If everyone decided that blueberries were a superfood and we all needed to eat half a pound of them a day, would we expect the long-term price of blueberries to rise? Not really – we’d expect more farmers to produce blueberries, and barring some kind of barrier to production we couldn’t overcome, for the long-term price of blueberries to remain roughly the same.

As the paper shows, while most G7 countries have experienced quite a lot of house price growth since 1980, the UK has had by far the most – Germany, Japan and Italy have had almost no inflation-adjusted increase in house prices, and the USA has experienced less than a doubling of prices over that time.

Since real interest rates have been similar across these countries over this period, real interest rates alone cannot explain the UK’s extremely high house price growth. Applying the sorts of supply and income elasticities that are present in Japan or Denmark (still considerably less elastic than the US) to the UK experience gives a much smaller real house price growth: 88%, instead of 173% that their model implies. Even when we only look at the national picture and do not focus in on the places like London where demand and costs are highest, something is badly wrong.

There is a second point that the authors mention: the constancy of rents as a percentage of income over time (adjusted for quality improvements, imperfectly). This is taken by some to mean that there is no problem in the rental market – and, hence, that the fundamental factors of supply and demand are working healthily in the housing market.

But think about what this actually means: every time someone gets a pay rise, a large fraction of that pay rise immediately is gobbled up by their rent. If everything I spent money on acted this way, pay rises would be meaningless – I would be no better off at all.

The paper’s authors find that around 40% of people’s incomes go on rent. That means that forty percent of whatever pay rises people have gotten for decades has gone to landowners rather than to them. In a market where supply was more elastic, we would not expect this to be the case. It isn’t the case in the markets for clothes or cars, or even for durable goods like ships or airplanes.

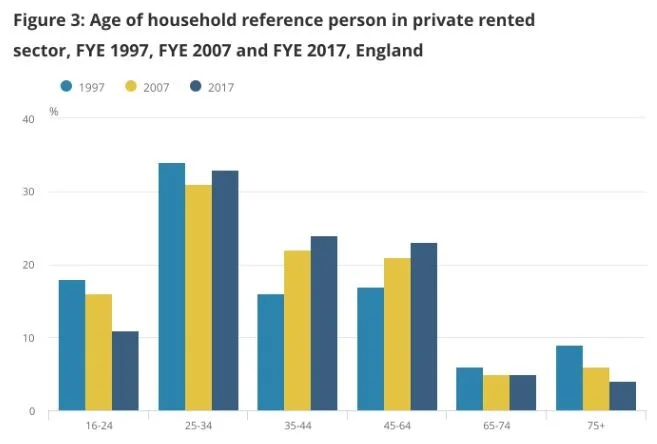

The proportion of renters has increased significantly over time as well, by from 13% to 20% in private rented accommodation in the ten years to 2017. And the age that people stop renting is rising too, so more and more people in their forties are still renting when previously they would have bought a house. So 40% of disposable income and pay rises going on rent is a much bigger problem now than it was thirty or forty years ago – a graph showing rents remaining constant as a share of income can obscure a huge change in the number and composition of people who are renting.

And this doesn’t apply to homeowners - the value of their asset rises when average wages rise. It’s only renters who see their future costs rise like this when incomes rise.

I regard this paper as an important, high quality contribution to the debate, and strong evidence that the supply side in Britain’s housing market is extremely broken. Moreover, it is the side of the equation we can do something to fix – real interest rates are driven by fundamental economic factors that governments can only indirectly affect, and with great difficulty, whereas the elasticity of housing supply is something that the government currently constrains directly via the planning system. And solving that may be less politically difficult than it seems.

A small observation about the Efficient Markets Hypothesis

We’re always amused by the manner in which all too many people don’t think through the implications of their own beliefs and contentions. In this specific case we’re talking about the Efficient Markets Hypothesis. Which comes in three flavours weak, semi-strong and strong. Which, roughly enough and in sequence, imply that all generally known information is in prices, all public information is in prices and all things known by anyone at all are in prices.

It tends to be that the more right-ish economically that you are the further along that spectrum your beliefs. Near every economist will run with the weak version, not all that many with the strong.

We also have the idea that there can be too much finance in an economy. That some to a lot of it is mere paper shuffling which produces no value. This belief is stronger the further left-ish your economic views, generally at least.

Which is, to us, interesting. Because the less market prices reflect knowledge then the more we require a finance industry to process data into information, no? That being what those financial markets do, give us a price based upon the trades that people make given their knowledge base. That is, if we believe the strong version of the EMH then we only need a small finance industry because not much processing of that information is necessary because it’s all already reflected in prices. Equally, if you hold with the weak version then a large finance industry should be necessary.

Yet - in general of course - the views are aligned entirely opposite. Those who believe the weak want a smaller finance industry, those the strong are just fine with what we’ve got.

Sure, we’ve our own thoughts on this - the strong holds because we have a large finance industry which rather aligns us with Robert Shiller on the point - but we do still think it’s interesting that the general positions don’t quite match up at either end of the respective arguments.

Richard Arkwright, industrial pioneer

Richard Arkwright, described as the "father of the modern industrial factory system," was born on December 23rd, 1732. Without formal schooling, he was taught to read and write by his cousin, then apprenticed to a barber. He was inventive from the beginning, creasing a new waterproof dye for the then-fashionable wigs.

He created a spinning frame to mechanize the thread-making by using wood and metal cylinders to replace people's fingers. It was initially powered by horses, and with a partner, Arkwright started up a horse-drawn factory at Nottingham. He took on investors from the stocking industry to set up the world's first water-powered textile mill at Cromford, employing 200 people to perform both carding and spinning. His new carding machine made thin, strong cotton thread to feed what were now called Arkwright's water frames.

His insight was to realize that mass-produced yarn could be made by applying external power, initially water, to semi-skilled labour operating machines. He was very much an entrepreneur as well an inventor, setting up a series of water mills across the Easy Midlands. He built cottages near his Cromford mill to accommodate the weavers and their families he attracted, employing whole families, including children, in his factories.

He also pioneered the use of steam power, using a steam engine at Wirksworth to refill the mill pond used to drive the water wheel that powered his machines. He employed thousands of people, and helped shape the early industrialized North of England, as well as helping to set up mills at Lanarkshire in Scotland. He was not popular. His attempt to secure a "grand patent" on his processes was rejected after dragging on for years, and one of his mills was destroyed in the anti-machinery riots of 1779. He was knighted for his work, however, and left a huge fortune of half a million pounds when he died.

Like the other pioneers of England's Industrial Revolution, he was breaking new ground. He changed the face of England, and then the world. Previous generations had looked forward to doing what their parents had done, but now, because of men like Arkwright, each generation would have to live in a world completely different from that of its predecessors.

His innovations caused upset as his machines made traditional crafts obsolete. His factories broke the closed shop of guilds and apprenticeships that had enabled craftsmen to fix prices. His methods produced cheap and affordable yarns that brought to ordinary people what had previously been affordable only to the well-to-do.

The system that he pioneered created wealth on an undreamed of scale, and lifted first England, then the world, out of the subsistence and starvation of a rural economy, and onto the upward path to create the resources that would later pay for sanitation and medicine, and then for education.

There are scholarships in his name that fund hundred of students to achieve the qualifications for university entrance and apprenticeships, especially in engineering. But his real memorial is the modern world itself, the world he entered as a pioneer and an innovator, and helped to shape.

It's a very odd definition of success

The aim of an economic system is to produce enough of something while still being able to produce the maximal amount of everything else. Producing too much of the one thing means that we are producing, well, too much of that and are thus gaining not as much of everything else as we could be getting. We are therefore poorer.

Which makes this a very odd definition of success:

Thousands of homes across Britain were offered the chance to earn extra money this month by turning their electric vehicles on to charge overnight or setting a timer on their laundry load. Customers on a new breed of “smart” tariff were effectively paid to help make use of the UK’s abundant wind power generation, which reached a record 16GW of electricity, to make up 45% of the generation mix for the first time.

It is an early glimpse of the increasingly important role that cheap, renewable energy will play in the decade ahead – and a timely reminder to the new government of the huge potential that could be harnessed with the right policies to support one of the UK’s fastest-growing industries.

Devoting resources to producing something in such glut that we quite literally could not give it away? We’re fine with dealing with whatever dangers it might be that climate change sends our way, even reducing them if that’s the correct option. But spraying societal wealth down the drain just doesn’t seem to be the correct response to anything at all.

First flight of the Blackbird

In great secrecy on December 22nd, 1964, one of the most awesome planes ever built was rolled out at Air Force Plant 42 in California, and took its first flight. On that very first flight it achieved a speed of Mach 3.4. This was the SR-71 Blackbird, a plane that played an honoured role in the Cold War

Wars are often started through uncertainty, when a potential aggressor is uncertain of the response. This makes intelligence extremely important; you need to know your enemy's capabilities. Behind the Iron Curtain NATO needed to assess the USSR's capabilities, and what aggressive potential it had. The US initially used the U2 spy plane, but it was becoming vulnerable to interception by missiles, and a successor was needed.

Kelly Johnson at Lockheed's "Skunk Works," created the SR-71. Its shape was designed to reflect radar beams, it was coated in radar-absorbent iron-ferrite paint, and its fuel was mixed to minimize exhaust trails. It could fly at over Mach 3 at 80,000 feet, and was able to outrun any enemy aircraft and missiles. It gathered massive reconnaissance on its many flights, identifying potential enemy positions and military assets. Its appearance was thrillingly exotic, and breathtakingly elegant. It became an icon.

It had ground-breaking technology. It was 85% heat-resistant titanium, with windows of quartz. During flights its exterior could exceed 500F, and when it landed, it had a long period to cool down before the crew could leave it or the ground crew could approach it. It leaked fuel on the runway at take-off because the tanks were designed to expand and seal with the heat once it was flying up to speed.

Its twin J58 engines needed vehicle-mounted starter engines to get them going, and moved to partial ramjet mode at high speeds and altitudes. It was soon breaking records for speeds and altitudes, though many remained long classified. It once established a New York to London record flight time of 1 hour and 54 minutes.

32 Blackbirds were built, and although 12 were damaged or lost in accidents, none was lost to enemy action, even though it was in harm's way many times. During the Vietnam war years, over 800 enemy missiles were fired at it, none successfully. It had missile attacks against it over Libya and North Korea, but it outran them all.

It served with the US Air Force for 32 years, from 1964 to 1998, and NASA operated the two last airworthy Blackbirds until 1999. Its missions helped keep the peace by keeping NATO apprised of possible enemy capabilities and deployment. It was finally superseded by reconnaissance satellites, but its career reminds us of the constant need to be on our guard, to be alert to possible enemy plans, and to construct defences to meet new offensive capabilities that our potential adversaries develop. The price of liberty is eternal vigilance, and the Blackbird performed an essential part of that vigilance. On the 55th anniversary of its maiden flight, we salute it.

The Keynesian ratchet

Note that we say ratchet, although racket is also a useful description.

Approximately 700,000 Americans will soon lose their benefits as the government tightens the regulations around stable work requirements for recipients, stretching the already scarce resources of the communities that Waide’s operation helps.

Those communities are often African American, raising the prospect that Trump’s move will put extra stress on minority families. Approximately one in three households using Snap benefits are African American. In general, African American households are more likely to experience food insecurity, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. In 2016, Snap helped more than 13 million African American households put food on the table, according to data from the US agriculture department’s fiscal year 2016 Snap Households Characteristic data.

Snap is food stamps, one of the major pieces of US spending upon - or for the benefit of perhaps - the poor.

One observation is that if it is black Americans who will lose most from this reduction in the program then it must be black Americans who gain most from it at present. Given the social background in the US insisting that welfare aids blacks most might not be the wisest political idea ever.

But that’s not our point here - nor is whether the current, past or future levels of Snap are correct in the overall sense. Rather, that ratchet.

For Snap eligibility was greatly expanded in those dark economic days of the first Obama Administration. We can argue that that was the correct economic response too, in that Keynesian manner. Increase the deficit, get money into the hands of the people who will spend it, thereby boosting the economy. We could even call it a version of Milton Friedman’s helicopter money.

OK. But implicit in that justification is that when the dark days have gone - possibly when there’s no longer an Obama Administration - then that stimulation of the economy should cease. But note what happens when this is suggested. Instead of a general agreement that we’re finished now with Keynesian stimulus we have the shouting that we’re stealing crusts from starveling babies.

That’s the Keynesian ratchet. Even if it is true that there should be deficit paid for stimulus the justification for the increased spending changes when it becomes time to reduce it again. So that the spending never is - or never should be - reduced in those better economic times.

All of which is rather why we agree with the later Keynes himself. Assume, again, that the stimulus should happen - we’re not sure we do agree with this but make that assumption. It should be done by cutting taxation, not increasing spending. Again as Keynes suggested, by cutting social security (national insurance for the UK) taxes. The benefit of this being that the clamour to revive state revenues, when the crisis is past, will be rather greater than that to reduce state spending.

That is, pro-poor tax cuts in recession will alleviate the problem without becoming a permanent part of the economic settlement. We abolish the ratchet.

Of course, we’re pro-pro-poor tax cuts all the time anyway but that’s a rather more structural matter.

Benjamin Disraeli, a strange Prime Minister

On December 21st, 1804, was born a man destined to become one of Britain's strangest Prime Ministers. This was Benjamin Disraeli. His background was ordinary, middle class, though he later romanticized it. Born and raised initially Jewish, his father renounced Judaism after a dispute with his synagogue, converted to Christianity, and had all four of his children baptized as Anglicans when young Benjamin was 12. This opened up the possibility of a political career, since Jews could not at that time take the Christian oath of allegiance without converting, at least nominally. In his 20th year, Disraeli changed the spelling of his name from D'Israeli to Disraeli.

As an MP, Disraeli was extrovert, even flashy. At times he wore white kid gloves with rings outside them. He was drawn to glamour and glitter, and loved celebrity. He wrote novels, including his famous political novels. In which his ideas were expressed by fictional characters.

Initially in Parliament he backed the landowning aristocrats in opposing Robert Peel's attempt to open the country to cheap imports by repealing the Corn Laws, laws which protected the incomes of the landowning classes. When the laws were repealed, Disraeli helped bring down Peel and split the party. When he later became first Chancellor, then Prime Minister, however, he refused to repeal them.

In office he followed Peel's policy of bidding for the support of voters newly-enfranchised by electoral reforms. He enacted measures to protect and assist workers, often in opposition to the merchant and manufacturing class who found Gladstone's Liberals more to their political taste. It was the age-old combination of king and peasants versus the barons that he was constructing, only in this case it was Tories and workers versus bosses.

Disraeli lowered taxes on malt to lower the cost of the workers' beer, and refused to reimpose the Corn Laws when efficient transatlantic freight, enabled by newly-efficient steam engines, brought in cheap harvests from the American mid-west. He passed Acts to support public health and education, and to enable low-cost housing to be built. He called it a "One Nation" policy, but it more resembled class politics designed to give his party a sold base among the new voters.

The icing on top of his cake was imperialism, hugely popular among the working classes. They might come low in the national pecking order, but they took immense pride in being members of the world's mightiest empire. Queen Victoria liked it, too, and preferred Disraeli to the somewhat cold and stern Gladstone. "She liked flattery," said Disraeli, "and I laid it on with a trowel."

There is a parallel with recent UK events, in that the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, seems to be forming a similar coalition, bidding for support in what were once the Labour heartlands of the Northern and Midland working classes. Like Disraeli, he appeals to the basic patriotism they embrace. His message is one of an independent and proud Britain that stands up to bullying and threats from overseas.

Whether Johnson will be as successful as Disraeli in forging and maintaining that coalition against the bubble politics of the urban and academic elite, as Disraeli did against the merchants and manufacturers, remains to be seen. As ever, time will tell, though the early portents look promising.

WeWork and Robert Shiller on the Efficient Markets Hypothesis

WeWork was and is, as well as being a hugely amusing tale of hubris, a lesson in the efficient markets hypothesis, the EMH.

As we might recall the little joke - economists aren’t all that good at this humour thing - the Nobel was awarded to Eugene Fama, Lars Peter Hansen and Robert Shiller, one for proving the EMH, the second for doing the maths, the third for disproving it. Which isn’t quite the way it did work. Shiller refined the idea.

That EMH not being a statement that markets are always the efficient way of doing things, nor that everything should be done by markets in order to be efficient. Rather, that markets are efficient at processing information. Thus things that are known are already in market prices.

Shiller’s addition was that this is only true when everyone in that market can trade their view. Thus, given the difficulty of going short housing the persistence and extremity of the American housing boom. And so his proposal that to limit future such problems there should be a futures market in house prices where people could bet on price falls. That would get the views of bears into market prices.

At which point, a comment on WeWork:

One of the great mysteries of modern finance is how to make money when you know there’s a bubble, or at least how to get much, much richer than everyone else. The obvious way is to bet against the bubble, but this is difficult, as its expansion can easily outlast one’s ability to finance the wager. It’s even harder if the bubble is primarily happening in the private markets, where it is very difficult, if not impossible, to directly bet against the fortunes of a company that you think is overvalued.

Quite so, it was the exposure of WeWork to those wider financial markets that precipitated the implosion. You know, the financial markets where a couple of months after the IPO people could go short the shares and thereby communicate their view that it was a dog. That echoing back in time to mean there was no IPO.

This also explaining why the EMH does indeed imply, even if not directly state, that markets are efficient ways of doing things. For the alternative to markets is command and control, usually by government. Which isn’t ever subject to that same reality confirming pressure of the opinions of those who are quite sure it’s a dog.

We offer HS2 as a confirmation of that contention. It’s only because it’s not subject to the oversight is people risking their own money that it’s lasted this long, isn’t it.