The government claims that lockdown exit will be triggered only by science. Science today gets the reverence that the middle ages accorded to religion. We need to look more closely. The experience of other countries leaving lockdown will be truly valuable. We must learn from Italy, Denmark and Germany and also Sweden which has had no lockdown at all.

The government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, has pinned his colours to the R mast: on 1st April, he stated we must get and keep “R, which is the average infection rate per person, below one.” R, the reproduction number, “is an indication of how much an infectious virus will spread in a population, and various things impact that value,” said Jonathan Ball, professor of molecular virology at the University of Nottingham. “The susceptibility, size and density of the population that the infection is introduced into matters, as well as the infectiousness of the virus itself.”

Estimates of R across Europe vary, not least because, as Imperial College modelling concedes, no one has any idea how many Covid-19 infections there have been. Their report, with over 50 authors, estimates R to have been about 3.87 before lockdowns. Following lockdowns and other interventions, they estimated a 62% fall to 1.43. As an example of facts not being allowed to get in the way of a good theory, the 30th March their report stated (p.6): “The estimated reproduction number for Sweden is higher, not because the mortality trends are significantly different from any other country, but as an artefact of our model, which assumes a smaller reduction in Rt [reproduction number at time t] because no full lockdown has been ordered so far.”

By contrast, on 1st April the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, also part of the government’s scientific advisory team, estimated pre-intervention R0 to be around 2.1 and a 70% reduction to 0.62 would result from lockdown and other interventions, e.g. social distancing. They asked 1,300 individuals in lockdown to list their contacts for the previous day and compared the results with an unrelated study in 2006. The research is not peer-reviewed and a number of caveats will be apparent but at least an effort was made to anchor it in reality.

In short, science is widely divided on pre-intervention reproduction numbers: on 13th March, the Journal of Travel Medicine reported “Our review found the average R0 to be 3.28 and median to be 2.79, which exceed WHO estimates from 1.4 to 2.5.”

Bandying R about is scientificating a simple measurement of whether the number of cases is increasing or decreasing and, if so, at what speed. Is infection accelerating or decelerating and by how much? It has nothing to do with the rate of deaths nor with prediction. And it is undermined by not knowing how many cases there are. As Jeremy Hunt in The Times on 21st April, has rightly pointed out, contact tracing is critical. That, as the Lancet on 28th February confirms, would also provide the necessary data for estimating, via sampling, and controlling total infections. It is odd that there has been little or no mention of contact tracing from the government or its scientific advisers.

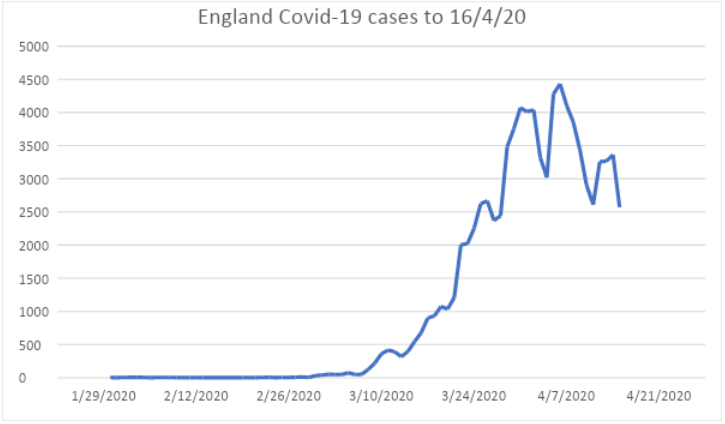

We do not need to track R, just the number of cases. Whatever the ideal, we must use the numbers we have. Deaths, sad and important though they be, are not relevant for our purpose. Non-hospitalised cases are not known and, again, do not impinge since those infected can recover at home as they do for common colds or flu. Remember that the object of lockdowns and other interventions is to moderate the effect on the NHS. Hospitalisations, or the “cases” numbers published, are the only leading indicator we have. Monitoring that needs no more than a simple graph, viz.;

The big bogey is the second wave. It is foolish to suggest that can be avoided, or even should be avoided. Minimising, or at least moderating, it is what matters. Whenever the lockdown exit begins, and contacts increase, a wave of some kind will follow. The issue is not when exit begins but how it is managed. It is extraordinary that such a simple distinction escapes the government’s scientific advisers. Furthermore, exit management needs to focus, for the reasons above, on the number of hospitalisations, or the closest proxy available. As that trails infections by between a week and 10 days, the exit should be in fortnightly steps to allow response to significant changes in trend.

Advice from the scientists has been questionable all along. On 20th March, the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) stated: “In fast moving situations, transparency should be at the heart of what the government does. We have therefore published the statements and the accompanying evidence to demonstrate how our understanding of COVID-19 has continued to evolve as new data emerges, and how SAGE’s advice has quickly adapted to new findings that reflect a changing situation.”

They then went on to say that the modelling could not be published as the modellers may wish to do so later in academic journals. Secondly, the site does show SAGE’s current understanding of the situation, but not its evolution. Thirdly, they present possible (guessed) scenarios but neither science nor proposals for government action. Their estimates of public compliance proved wildly wrong and even their estimate that 75% of 80+ year olds would not go to work or attend schools were, surprising as it may seem, low.

All this is reminiscent of the time the Ministry of Agriculture decided that too much guesswork was involved in estimating the weight of pigs. A committee of science professors from obscure universities was formed. After deliberation, they recommended the acquisition of a plank with the pig tied to one end and a basket to the other. The plank should be carefully placed with the mid-point on a low wall and the basket gradually filled with stones. When the plank is balanced, the farmer should guess the weight of the stones.