We can't help thinking there might be a connection here Polly

Polly Toynbee tells us that:

The next few years will be a carbon copy of post-2010 austerity, with a massive extra 8% cut to most public services – worse this time for coming on top of the last lost decade and the damage done by this crisis.

That may be a good idea, may not be, that’s not the point we wish to, umm, point to. Rather:

No one thought the economy would plummet by an unthinkable 10%,

That’s the damage that has been done by this crisis. There is 10% less of everything. That’s what the economy is, that everything, and a fall in GDP of 10% really is saying that all production, or all incomes, or all consumption - any one of the three equalling either of the other two - have fallen by 10%.

If we devote that same portion of everything we have to those public services then spending upon them should fall by 10% that is. As it happens the prediction - threat according to Polly - is that such diversion of resources will only fall by 8%. That is, there will be a rise in the portion of everything we devote to such things.

Which we can prove by looking at it the other way, the tax burden is predicted to rise by percentage points of GDP over the same period. That is, given those very numbers that Polly presents us with, far from having cuts in the public sector we are expanding it, we are spending a greater portion of everything we have upon them.

We don;t think we ought to be but then again that’s another point to be making.

We would regard this as a stunning victory ourselves

We do not mean to even imply, let alone state, that all economic policy in 2020 was entirely and wholly wonderful. We would however insist that this is a pretty good outcome:

Half of British workers had a real-terms pay cut in the year to autumn 2020, despite official figures showing the fastest earnings growth in almost two decades, research by the Resolution Foundation suggests.

The thinktank said official figures on average weekly earnings had been “hugely disrupted” by the large number of workers furloughed, and that the headline rates were “too good to be true”.

Data showing average weekly earnings growth of 4.5% in late 2020 – its highest level since 2002 – did not reflect how pay packets had changed, it said, and was distorted by changes in the makeup of the workforce, with many in low-paid work losing jobs during the pandemic.

The foundation said its research indicated that the median annual pay rise was 0.6% last autumn, which once inflation was taken into account meant half of workers had experienced a 0.2% pay cut over 12 months.

It’s worth reminding ourselves that UK GDP fell 9.9% in 2020. Yes, we know that the year to autumn 2020 and the calendar year 2020 are not exactly the same time period.

GDP is, by definition, all incomes. So, we’ve a 10% drop in aggregate incomes and if the biggest complaint is that half of workers suffered a 0.2% pay fall then we’d regard that as something of a victory. The assumption must be that the fall in income was concentrated among the higher income groups.

It reminds us rather of George Monbiot’s reaction to Fukushima. Absolutely the worst possible disaster happened, three reactors melt down as a result of an earthquake and tsunami, and the number of deaths from the nuclear part of that accident seems to be zero. We should therefore conclude, with George, that nuclear has its merits.

We have the worst economic year for over three centuries and the complaint is a 0.2% fall in certain incomes? What the heck do we have to do to be able to declare a win here?

Is Council Tax fair?

Is it fair that a little old lady, in her family home, impoverished and using few council services, pays far more council tax than a family of large wage earners in social housing and using most of the services? Council tax is based on an out-of-date assessment of the value of one’s home. It is based on the daft assumption that the wealthy live in expensive properties and the deprived in cheap accommodation. Moving to local income tax, as has been long discussed, would be a start.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies concluded that it would help accountability and should be a flat rate. The bureaucracy should not be a problem as it could be based on the same assessments as the HMRC uses for national income tax. That would save the need for periodic property valuations. Other countries use sales tax (USA) or VAT (Canada) to provide local government revenue.

Another daft feature of the UK system is the reliance by local government on Whitehall handouts. The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) employs about half of its 4,609 people devising myriad arcane ways of using national tax revenue to induce local government to do what it wants. Nanny knows best. Perish the thought that local governments should do what their locals want. The simple truth is that the taxpayers’ money could go straight to local government in the form of local income tax, or VAT receipts or whatever, and the MHCLG should be abolished. If Robert Jenrick pulled the plug on his department, greater things would await him.

Councils have not been helped by the government’s financial pressures since 2008. When choosing between restraining one’s own spending or someone else’s, it is no surprise Whitehall has preferred the latter. In 2009/10 MHCLG provided two thirds of local government expenditure. By 2018/19 it was less than half. The squeeze on local government spending partly accounts for the increasingly poor provision of adult social care which is mostly funded by MHCLG.

What MHCLG wants to achieve, in its redistribution of our money to local authorities, is far from clear. It could be seeking equality in the sense of funding all councils at levels they can provide equivalent services or rewarding those that provide the best taxpayer value or gerrymandering or giving preference to particular services such as social care. This is a difficult area: in an ideal world, all councils would be equally efficient and provide equivalent services, bearing in mind the different needs of affluent and deprived areas and costs, e.g. the annual costs of carers. But this is not an ideal world: Wandsworth’s Band D council tax is £845 compared with £1,959 in their neighbouring Richmond and £2,057 in the only slightly further Kingston. The services are not that different and the rates of council tax are after MHCLG have done whatever harmonisation they may do.

Devolving expenditure to units closer to the taxpayer is supposed to improve accountability and taxpayer value, and ensure that expenditure is more closely aligned with what the locals want. In practice, Wandsworth aside, MHCLG does not do any of those things. And there are other ministries that should also be devolved, notably Education and Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Why should a Whitehall committee decide that a Bradford theatre was more worthy of support than one in Leeds, or vice versa. We have much to learn from how the Swiss central government and cantons exercise their roles.

There are two main explanations for the variation in councils’ competence: governance and voter apathy. With two levels of local councils, e.g. County and District, there are not enough high grade councillors to go round. A start could be made by creating more Unitaries. Norfolk voted against that purely because turkeys don’t vote for Christmas. London is a special case. The central bureaucracy has grown by 33% under Sadiq Khan up to 2018. Whilst a few things need London-wide policies, the lion’s share of London government should be undertaken by the boroughs – perhaps with some mergers. After all, London managed quite well over the 14 years from Margaret Thatcher’s abolition of the Greater London Council in 1986 to Tony Blair’s reinstatement as the Greater London Authority in 2000.

The other reason for poor council performance is public indifference. The media fully covers national politics but gives scant attention to local government. The demise of local media is partly to blame. Apart from sideshows, like toppling statues and councillors awarding themselves higher than inflation rises in expense allowances, there is little of interest to report. Accountability needs news to be created.

The Audit Commission was created in 1983 to keep local council books in order but by 2015 the government decided it had become “wasteful, ineffective and undemocratic” and closing it would save £1.2bn over 10 years. Auditing was put out to the private sector. The trouble is that auditors (and I used to be one) are nice to their clients on account of wanting to keep the business. They are professional but prefer to rectify problems discreetly. The National Audit Office (NAO) operates far more openly. It has two branches, audit and taxpayer value, and its reports to the Public Accounts Committee pull no punches. We need a Local Audit Office (LAO) that operates in much the same way, reporting to audit committees that are wholly independent of their councils. The LAO reports need to be publicised locally.

The Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman claims to provide statistics on councils’ performance that are only about how complaints were dealt with. IMPOWER collects data enabling councils to compare their performance with similar local authorities. Unfortunately, confidentiality is part of the deal (to acquire the data) so the councils’ electorates are none the wiser.

Some issues do get local media attention. In some seaside areas and in Wales, second homes is one such issue. Second homes in these areas are alleged to deprive the less affluent locals, farm workers for example, from buying starter homes and to raise house prices in general. Second homes are often rarely visited so village schools, post offices, shops, and pubs close. In short, villages die. Worse still, the owners can claim they are making the second homes available as holiday rentals (they do not actually have to rent them out) and thus avoid council tax and also the income is below the business rates threshold. This minor scandal has been drawn to the attention of MHCLG but apparently they do not have enough staff to deal with it. It would take them 10 minutes to draw up a regulation making local councils responsible for sorting it out.

Two final caveats: if local income tax becomes the main revenue for local authorities it should be progressive, like national income tax, and not a flat rate. Local authorities should not be allowed to beat their budgets by borrowing. Managing inflation and protecting our currency are matters for the Bank of England and HM Treasury.

The second homes case history illustrates the need to devolve local matters to local councils and make local taxation both rational and fair.

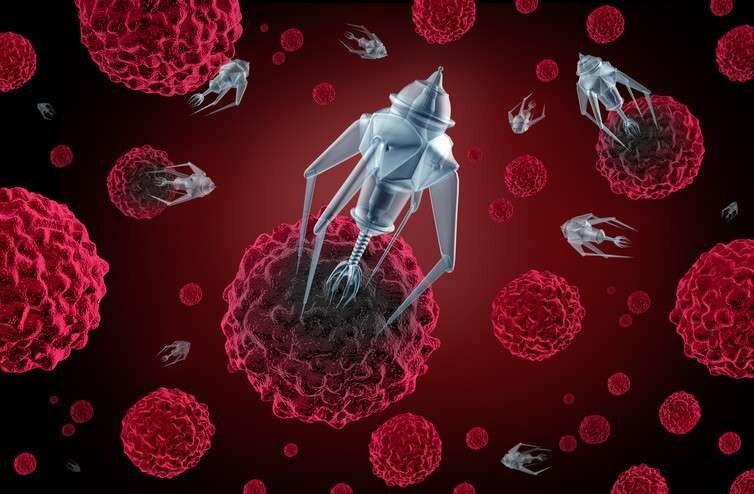

Reasons for optimism - nanotechnology

Nanotechnology has already transformed many materials, and is in the process of tailor-making many more to our specifications. It is a reason to be optimistic that newly developed materials will be enabling us the achieve things thought impossible less than a generation ago.

It is basically a technology that manages to manipulate the molecular structure of materials to alter their properties. A nanometre is one-billionth of a metre, about 80,000 times thinner than a human hair. This is the scale on which atoms and the molecules they make are measured, and technology at this level involves controlling individual atoms and molecules. It has already enabled revolutionary applications.

New forms of carbon have been developed, including nanotubes and nanopillars that are used to make solar panels more efficient. Graphene, a single atom thick, is harder than steel and lighter than aluminium. So-called “first generation” passive nanomaterials are used in surface coatings to allow golf balls to fly straighter and to enable windows to be self-cleaning. Bandages infused with silver nanoparticles enable cuts to heal faster. Clothing impregnated with nanoparticles has been developed to last longer, stay cleaner, and enable people to keep cool in hot weather.

Steel embedded with nanoparticles makes possible beams that are lighter and thinner, yet stronger. A nanocomposite coating for oil industry pipes makes them more resistant to corrosion. Nanotechnology makes its mark in electronics, energy, the food industry and in air and water purification.

One of the most exciting and promising applications is in the field of biomedicine, where it plays a role in tissue engineering, replicating with nanoparticles the body’s cell structure in order to help it repair damaged tissue. It is playing an increasing role in biosensors to give early warning of developing dangers, and in accurately targeting drug delivery to precise locations. Some nanomaterials are being specifically designed to seek out and destroy cancer cells without damaging healthy ones. This raises the prospect of the elusive ‘cure for cancer’ long thought impossible.

Optimism about nanotechnology has been tempered by concerns about possible hazards brought about by absorption of nanoparticles into the body. It has led to safety procedures being incorporated into the manufacture and use of nanoparticles, and into monitoring of their possible effects. One alarmist notion was that self-replicating nano machines would consume the environment and turn the entire planet into a “grey goo.” Prince Charles raised this prospect, calling on the Royal Society to investigate the risks, to the puzzlement of UK nanotechnologists unaware of that particular scenario.

Some progress in nanotechnology breakthroughs now goes unannounced, lest predatory NGOs use it in scare stories to raise funds with, as they did with genetically modified organisms, causing politicians to impose arbitrary controls. While it makes sense for nanotechnologists to shun the limelight, it does mean that progress is slower than it would be if it were all in the public domain.

It does mean that some of the breakthroughs will be announced suddenly when complete, rather than while still under development. We can look forward to periodic unveiling of advances in nanotechnology that give us access to better materials, better medicine, and which improve many of the things we routinely do by enabling us to do them better.

Some statistics just aren't all that surprising

Torsten Bell tells us that:

First, big cities have more than their share of poor families – overall, Londoners have below average disposable incomes.

Well, not so much really. Londoners have below average disposable incomes after housing costs and above before. Which, given that housing in London is more expensive than it is in other areas of the country isn’t, in fact, all that much of a surprise.

However, this is also important. For the usual measures of inequality across Britain keep telling us - and thus the levelling up mantra - that Britain is unequal across geography. Which is measured by the pre-housing costs measures. But if housing costs different amounts then inequality, across that geography, is lower than generally measured, isn’t it?

This extends further as well. The costs of near everything vary around the country - that first rural experience of London’s beer prices usually does bring an outburst of guttural Anglo Saxonisms.

Britain, by the only measure that can possibly matter - inequality of consumption - is very much less unequal than is generally assumed or measured. Therefore, of course, we need to do very much less about it.

If only Owen Jones were capable of observation

According to Owen Jones the desecration of the environment is all about profit and the pursuit of it:

This is not a bug of capitalism: it is a central feature. The remorseless search for profit – and an economic system that enables the capture of our political systems by multinational companies with bottomless pockets – represents a fatal threat to our health, to our lives, and to our planet. Without a determined effort to drive back the political power of these corporate titans – which means questioning the very fundamentals of our economic system – our planet will continue to perish. Time is not on our side.

It’s necessary to be remarkably unobservant to end up in this position. A consideration of economic systems where profit did not, or does not, exist gives us places which are vastly more polluted than those where profit is sought. Looking east from the Berlin Wall in 1989 did not reveal a green and verdant environment after all.

It’s possible to be a little more detailed as well. Richer people in richer places have more income to devote to environmental preservation. That blend of capitalism and markets produces richer people better than any other economic system. Therefore the capitalist environments are cleaner - that environmental Kuznets curve. Again with the detail, that we consumers prefer cleaner environments means that those trying to profit from our choices are edged toward being cleaner.

But back to basics here. How can anyone observe such stinking messes as the Aral Sea and claim that it’s the pursuit of profit that damages the environment? From which we must conclude that Owen doesn’t observe.

But then we knew that.

Not taxing something is not a subsidy

There are claims that not taxing something, or even not raising the tax on something, is a subsidy:

UK slashes grants for electric car buyers while retaining petrol vehicle support

What petrol vehicle support?

The cut is likely to be controversial, only a fortnight after the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, extended a generous implicit subsidy for drivers of petrol and diesels by freezing fuel duty.

Not raising tax is neither an implicit nor, obviously, explicit, subsidy. Not increasing income tax is not a subsidy to people working for a living, not increasing VAT is not a subsidy to consumers.

It is possible to argue about externalities of course. Emissions have effects, those are costs that an activity might not be paying, that could be, with a squint, a subsidy. As we’ve pointed out a number of times over the years this is not true of petrol or diesel in the UK.

As we know the Stern Review told us that those social costs of carbon are $80 per tonne Co2-e. This is 11 pence per litre of diesel. That would then, to cover those externalities, be the righteous and just tax to adjust market prices. Since the fuel duty escalator was introduced by Ken Clarke - to “meet our Rio commitments” - the escalator has added 25 pence per litre. At least that’s what it was last time we went and counted.

That is, far from being subsidised by under-taxation to corral those externalities petrol and diesel are over-taxed. Do note that this is not some strange neoliberal construction, this is simply a straight reading of that insistence contained within the basic climate change report itself.

We can approach the calculation another way too. Total UK emissions are of the half a billion tonnes order. At $80 a tonne that’s around the £30 billion mark for the correct tax to adjust for those externalities. Fuel duty alone costs consumers about that amount. If anything - again, not some weird construction but the plain and open reading of the Stern case itself - petrol and diesel are over-taxed on climate change grounds and all other emissions in the economy under-taxed.

Freezing fuel duty is not a subsidy, implicit or of any other kind. Don’t let anyone tell you different.

Why William Nordhaus was right about climate change policy

As every economist knows if climate change is a problem that requires a solution then that solution is a carbon tax. Within that, however, is an argument which can be described as Stern v Nordhaus. No, this is not about discount rates, rather, about the capital cycle.

Stern said we should have the $80 tax and have it now. This is to internalise those externalities upon everything. But this means that we suddenly make uneconomic things which still have considerable useful life in them.

Nordhaus, on the other hand, points out that climate change is a long term problem. We can - and should - thus reduce the cost of dealing with it by using up that installed base and only replacing it with emissions free technology when we come to replace it anyway. Thus the carbon tax should start small - $10 say - and ramp up over time to something that forces new tech when we are replacing anyway - say $240.

Nordhaus was and is right:

However, this won’t be enough for the sector go green. Chris McDonald, chief executive of the Metals Processing Institute, estimates it would cost between £6bn and £7bn to decarbonise the UK’s steel plants, assuming they were replaced by new facilities. Eurofer says the entire EU and UK steel industry going green by 2050 would push up production costs by between 35pc and 100pc per tonne.

“It will be a huge challenge to fundamentally transform how steel is produced,” says Gareth Stace, director of UK Steel, warning his energy-hungry industry already faces higher costs than rivals in Europe.

Whether or not the UK should be producing virgin steel is an interesting question. There are those that say we must be able to do so on security grounds and the like. But we don’t mine iron ore here and we’re not going to start - again - either. So having a capacity to manufacture from raw materials doesn’t provide that security anyway.

But assume that we must have that capacity. We can use, as we currently do, blast furnaces and coking coal and that has high emissions. We can also use the much newer technology of direct reduction. This requires hydrogen and we’ve not a green supply of that yet but perhaps we will have. This has very low to no emissions.

The Stern to Nordhaus question is when should we replace those blast with direct? Given the long term nature of the problem when we’re about to tear down the old ones anyway, whenever that happens to be. Build the new plant with the new technology, yes, but why blow up a few £ billions worth of perfectly functional plant before we have to?

That means that we don’t in fact have a £6 to £7 billion bill to decarbonise. Now the cost of direct reduction systems is their cost minus the money we’re not going to spend on rebuilding or creating anew blast furnaces. A bill that, when properly calculated, is probably negative.

Of course, we could instead drop the idea of making iron and steel from virgin material altogether and just reprocess scrap in electric arc furnaces but then where’s the fun in that? It’s obvious, economic and requires no government - following that path would allow no strutting upon the national stage, would it, nor dipping into the pockets of the populace?

Latest from the MoD: It’s only money

Whitehall

London SW1

“Humphrey.”

“Yes, Minister?”

“The Public Accounts Committee is grumbling that our plans are unaffordable and have been in every year since 2013. The MoD is only planning to spend £181 billion over the next 10 years on equipment for our armed forces. I take it we need every penny?”

“The National Audit Office did indeed say previous years were unaffordable. Consistency is important, Minister. We have a black hole accounting system: now you see it, now you do not. When you welcomed the PM’s promise of an extra £16.5 billion, you may not have realised that we had already spent it, so it would not be extra at all.”

“No, Humphrey, I did not. Well at least if we’ve been spending all that money, we must now be match-fit: our troops, tanks and other equipment must be world class.”

“Well the truth is that we haven’t been able to recruit enough troops and we have not actually been able to introduce much new equipment. At 135,444 trained troops, we were 8.4% below strength last April. Mark you, we did also have 61,500 military personnel either under training or working in the MoD, helping us disburse our funding.”

“Difficult work spending money, Humphrey? My wife doesn’t have any trouble with it.”

“The nation demands it, Minister. As of October 2020, our MoD civilian personnel strength was 58,850. But you should add about 40,000 military personnel, which is the 61,500, less those under training.”

“So for every four trained troops we have three dedicated money spenders?”

“You could put it that way, but we do at least have the tanks we think we should have. That is because there is not much call for them these days.”

“We had 27,528 tanks and self-propelled guns in WWII, Humphrey. How many can we muster now?” [1]

“About 220 and they are so out of date that one third of them will have to be scrapped. The other 150 will be upgraded at a cost of £1.2 billion.”

“That’s £8 million a tank just for refurbishing it?”

“Excellent value, Minister.”

“Humphrey, I know you think I got this job only because I know nothing about military matters but one of the chaps I play golf with is an American general. He tells me they make about 500 M1 Abrams tanks a year and each costs less than £8M, brand spanking new. So why do we mess about refurbishing ours, which no doubt will take years, when we could get a couple of hundred M1 Abrams right away?”

“Well, that would not be the British way, Minister, and they probably have left hand drive.”

“British way? We haven’t made any tanks since 2017, so far as I know, and have no plans to make any in future because tanks are yesterday’s weaponry.”

“Not at all, Minister, we plan to re-tank by using German guns on Swedish chassis.”

“The cavalry will like that: the Swedish chassis goes backwards faster than forwards.”

“That is rather an elderly bon mot, Minister.”

“So are you really telling me, Humphrey, that we’ve spent over £130 billion on military equipment over the last 10 years and ended up with a pile of outmoded junk. What state of the art gear did we actually receive?”

“Well, to be less than my circumlocutional self, Minister, I would have to say ‘not a lot’. The variations to specification and cancellations are very expensive. My civil servant colleagues do a wonderful job but we do have trouble with the transitioning military. They come in from playing war games on the Salisbury Plain, knowing nothing but thinking they do. They are horrified by what is on order and change the specifications which delays everything by another few years, and puts the prices up. We have to pay new design fees, cancellations and advances. Then the next lot come in and do the same again.”

“So we are paying billions not to have military equipment?”

“Indeed Minister. Critics believe we are constantly running around in ever-diminishing circles but they do not comprehend the rigorous processes we have to observe.”

“Sounds like the Oozlum bird to me. The imperative that one has to have bespoke weaponry is fostered by the staff officers worrying about their next employment. Humphrey, have you any idea what a Saville Row suit costs these days?”

“No Minister. I find the Army and Navy Stores to be quite satisfactory.”

“Well that’s my point, Humphrey. You get your suits off the peg and we should buy our tanks, rifles, scout cars and such like off the world market – even from the Americans. At least they would then be compatible.”

“We have to protect the British defence industry,”

“Nuclear warheads are another example of waste. We may have invented them but how many have we ever dropped in anger?”

“None, Minister, as you know. Are you trying to make a point?”

“I am. We don’t intend to drop any in the future either and we signed up to reducing their number.”

“So?”

“Why are we actually increasing their number by 30% at a cost of God knows what?”

“As we make our own nuclear warheads, we regard the expenditure, not as a cost, but as a contribution to our economy. Of course, we’ll never use them but they signal that we are a Global Power. And the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons is so woolly we can do what we like. It is really just a game of tennis between Russia and the US with the rest of us spectators.”

“I thought you were going to give me a lecture on deterrence. The funny thing Humphrey is that half of our submarines built to carry the new ICBMs actually patrol empty because MI6 says the deterrent effect is the same. So we don’t have to make all these new warheads at all. We can just pretend we have and put the money into our black hole. And we can build smaller submarines too,”

“Minister, the White Paper will be released on 22nd March and that will surely resolve all your concerns.”

“Jolly good show. You must get me a copy.”

[1] Evans, Charles; McWilliams, Alec; Whitworth, Sam; Birch, David (2004). The Rolls Royce Meteor. Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust. ISBN 1-872922-24-4.

If only Jonathan Porritt knew what a technology is

Jonathan Porritt wants us all to understand that it will be renewables, not nuclear or hydrogen, that will power our future world. Well, maybe, possibly that is the way that it will pan out. We don’t particularly mind either, our concern is that civilisation does get powered and at the least overall cost. Which may or may not coincide with the exclusive use of renewables.

However, buried within the argument is a horrible piece of ignorance:

Rather than being the solution we have been waiting for, this nuclear/hydrogen development would actually be a disastrous techno-fix.

There’s nothing wrong with a techno-fix, indeed there’s everything right with one. For a technology is simply a way of doing something. Capitalism is a technology, it’s a way of doing the ownership and financing of productive assets. Socialism is a technology, a useful way of making sure there are too few productive assets to be owned and or financed. Nuclear is a technology, hydrogen is a technology, windmills, solar cells, dams, they’re all technologies, as is doing without anything other than animal and human muscle power a technology.

That is, every approach to doing anything is a techno-fix. All that Porritt is offering is a different techno-fix and one that we should evaluate on that basis alone. Does this technology fix the problem better than that other one?

We strongly suspect not which is why the scary words he’s offering about the alternatives but the base point still remains. Methods of fixing problems are, by definition, technologies, thus everything is indeed a techno-fix.