Authored by:

Connor Axiotes (Adam Smith Institute)

Nikhil Woodruff (UBI Centre & Policy Engine)

Scott Santens (Humanity Forward)

‘Automation has been transforming the labour market for decades and the development of generative AI is about to kick that into overdrive. We don't even need artificial general intelligence in order for a universal basic income to make sense. Market economies are fuelled by customers with discretionary income to spend, and the more people are unable to afford anything but their basic needs, the harder it is for employers to find customers to sustain their businesses. The need for UBI also goes beyond modernising welfare systems. It could be seen as a rightful dividend to those whose data provided the capital to train large generative transformers like GPT-4, which was all of us’ - Scott Santens, author, Basic Income researcher, and Senior Advisor to Andrew Yang’s Humanity Forward.

* * *

Sam Altman, the CEO of perhaps the most consequential artificial intelligence (AI) lab of the few years, OpenAI, imagines: “Artificial intelligence will create so much wealth that every adult in the United States could be paid $13,500 per year from its windfall as soon as 10 years from now.” He is referring to a Universal Basic Income (UBI) financed from the windfall profits of future AI systems. Altman believes that as AI continues to advance it will become more economically productive than human labour, causing the latter to “fall towards zero.”

Why is AI different?

In order for the price of some labour to fall to zero, AI systems will have to reach a point of generality - meaning the AI can do any task that a human can do but to a superhuman level. Some call this artificial general intelligence (AGI). It is at this point we believe there is a non-negligible chance these systems could replace many domains of both physical (which to some extent has already started happening) and cognitive human labour. It is the chance of the latter occurring which is particularly concerning.

We also do not yet know what emergent properties might pop up which were not intended in the initial design of the AI system, which may present itself post-deployment of an AI system. In addition, some believe an AGI would also display agency. Agency in an AI system would mean an ability to plan and execute its own objectives and goals. Both emerging properties and agency have the potential to make this technology unusually likely to replace cognitive as well as physical labour, as human labour’s comparative advantage of brain power becomes less apparent.

Research by OpenAI in March 2023 found that ‘around 80% of the U.S. workforce could have at least 10% of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19% of workers may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted.’ Gulp. Their paper examines the potential labour market impact of large language models (LLMs), like OpenAI's GPT, focusing on the tasks they can perform and their implications for employment and wages.

The authors emphasise that while LLMs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities, their real-world applications and overall impact on the labour market are still not fully understood. They work out that LLMs have the potential to directly impact approximately 32% of the US labour market, primarily in occupations that involve information processing and communication tasks.

But what if we are wrong... again? Technology doesn’t seem to cause lasting unemployment effects?

It seems as though transformative technologies have always complemented labour even if shorter-term employment shocks were experienced. Even when technology had made people unemployed in a specific sector, that pesky invisible hand of the market seemed to ensure industry elsewhere popped up and human labour was never very far from a job. So why would any other transformative technology be any different? Are we just another group of Luddite’s heading for the same egg-on-our-face fate?

We think this time it might be different

Due to the aforementioned properties and agency of AGI, we believe this time it will be different. Mainly because it will touch physical and cognitive labour with such efficiency, and leave humans with little comparative advantage with which to earn a proper market wage.

And so, we proceed in this piece under the assumption that an AGI with superhuman abilities in all human tasks - and the agency to plan and execute its own strategies - will, we believe, have significant sticky unemployment effects on lower skilled occupations as a conservative minimum estimate. We assume the economy is static and no other jobs can replace - with a liveable income - the jobs formerly lost by the now relatively (compared to the AGIs) economically unproductive labour.

And so the question arises, how would a Government go about finding a policy that might mitigate these effects? At the Adam Smith Institute, we have advocated for this policy for years, initially with the aim of simplifying the welfare system and for being a more effective and less regressive form of redistribution: a basic income.

A cumbersome state and an agile problem

The difficulty with ensuring that the state is responsive to the impacts of AI is largely because we do not yet know in what form AI’s disruption will take. If it is to be large-scale unemployment, strengthened unemployment insurance might appear a natural response. Or if employment incomes fall but jobs remain, in-work benefits might bear the strain.

But both of these countermeasures have their weaknesses. Interacting with the bureaucracy around modern welfare systems is time-consuming and undignified - so much so that around a quarter of eligible recipients never make it through. Ironically, this failure to target intended recipients is seen almost exclusively in programs that impose income eligibility conditions in the very name of ‘targeting’: unconditional cash programs like the Child Benefit have almost perfect accuracy in reaching their targets.

Unconditional cash therefore (or specifically: a universal basic income) may represent the only mechanism to ensure income stability for those who need it, whatever form the AI intervention takes. Critics of UBI often point to the high cost of the cash payments, and the substantial broad-based rises in taxes we’d need to fund them, as disqualifying factors. But the notion that the current welfare system avoids this is an illusion.

Many also recoil at the notion of a 50 percent flat tax, but see no issue with our 55 percent rate on income paid by some Universal Credit recipients. Means-tested benefits are not the magically targeted free-lunch that they might appear to be: they are by definition equivalent unconditional cash payments combined with a very high tax rate paid exclusively by some welfare recipients.

If the government proposed a large UBI funded by raising the National Insurance main tax rate from 12 percent to 55 percent, public support might not be very forthcoming. But that’s almost a mirror image of what Universal Credit is. The only difference is that UBI is administratively far more efficient.

But if a UBI were to be introduced, this should only be done with the abolition of much of the current welfare and benefit system in the UK and over a period of 5 to 10 years; total benefit spending is forecast to be £255 billion in 2023-24.

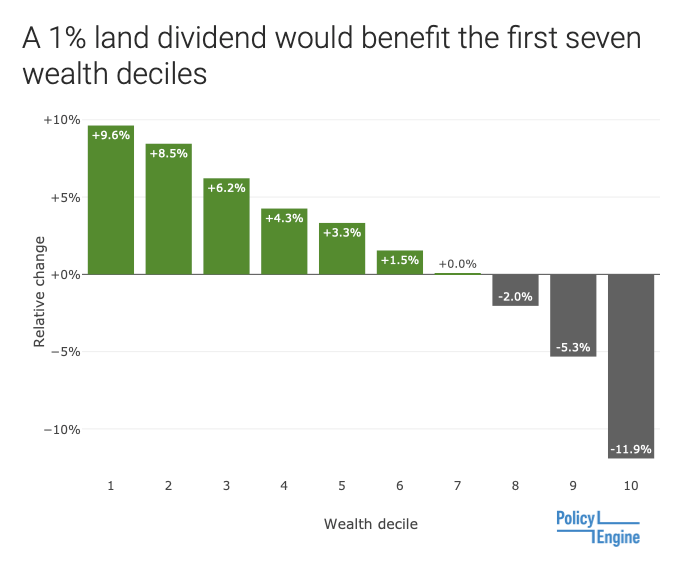

Broad tax rises on income could be one way to fund these cash payments, though critics would rightly point to negative labour supply responses. Taxes on natural commons could present an alternative: a 1% land value tax could raise enough to fund a £24 per week dividend.