So how do problems get solved?

That British retail is changing is obvious enough. The question is, well, what to do about it? Perhaps we should have a plan? Some people who don’t know much about it all, have no particular incentive to get it right, could impose their prejudices upon everyone else? Or, of course, we could not use politics to try to solve this problem:

More than half of the 497 department stores closed across Britain in the five years to November remain vacant,

Quite what such buildings should be used for next we don’t know. More to the point, that they’re - half of them - still empty means no one else does either. Perhaps they should become housing. Or the buildings razed and a park put in place. Or something else be sold from them, like go-kart rides.

The thing being that we have a system to work this out. It’s that market of course. Folks try all sorts of different things and somewhere along the line something that does in fact work will be stumbled across. At which point the greedy capitalists owning the other buildings will take note and try to do the same thing. The universe of possible solutions is best explored by those with the local knowledge and the incentives to conduct the experiments.

As The Observer tells us in fact:

Wolfson may have the best ideas about what comes Next for shops

Seems likely to us. Long time industry professional who is actually paid, daily, to work out what to do with shops might be just the person to work out what to do with shops. The contribution that politics can make to all of this is to give him, and all his contemporaries, the room and freedom to do that experimentation.

That is, hands off and leave it alone. As nurse used to say, if you keep picking at it you’ll only make it worse.

We're really quite convinced that trade doesn't work this way

A fundamental error here:

The war of words with the EU over vaccines has escalated as France’s foreign minister claimed Britain will struggle to source second Covid jabs but that Brussels would not be “blackmailed” into exporting doses to solve the problem.

It’s not Brussels exporting anything. For it is not countries - nor cities - that trade. It is individuals and groups of individuals as companies that trade. It is not even true that it is a political unit that trades.

Some people who have a production facility that happens to be located in a pace where the rule of Brussels holds sway wish to trade with some other people outside that area where the rule of Brussels holds sway. That that external group is the government of another country still doesn’t make it countries that trade with each other. Nor political groupings that do so.

We could claim this error comes from the French Foreign Minster, we could say it’s the journalism of The Guardian at fault here. But it is still true that trade is between people and groups of them, not some reification of political power. The European Union, Brussels, France, they do not, never have done and won’t trade with anyone.

Now that we all properly understand that the correct response to the claim about preventing trade is clear. Who the heck are you to stop people peaceably exchanging with with other? Butt out matey.

Yes, sadly, politics is necessary because we do need a method of making sure the bins are emptied but that’s what the process is for, not interfering in matters that work entirely happily without that process.

All your trade are belong to us

There is a consistent error out there in that people keep thinking that it is the people selling the stuff who garner the advantage in trade. Thus we get the absurdity of people insisting that we must retaliate when people refuse to buy our production - retaliate by making ourselves poorer by refusing to buy, or taxing ourselves for buying, those lovely things made by Johnny Foreigner.

Sometimes though reality does intervene. A ship is. most amusingly, stuck in the Suez Canal and trade is thus interrupted:

Consumers pay price of snarl-up in Suez Canal

Quite so, as it is consumers who benefit from trade it is consumers who pay the price - by not gaining the benefits - of an interruption in trade. This is thus true of tariffs, quotas, Buy British and all the rest.

As we were told getting on for a century ago, trade protection is as:

…to dump rocks into our harbors because other nations have rocky coasts…

Or, to block our canals because others have the mishap of having blocked their own. Just one of those evergreen truths we need to recall. The only logical trade stance is unilateral free trade.

This is not a greatly convincing argument

Owen Jones tells us that:

Given industrial scale tax avoidance on the part of so many large corporations, here is an argument that needs reiterating time and time again. Without much demonised state largesse, no company could profit. The state provides them with roads and other basic infrastructure, and protects their property. It educates their workforce and, through public healthcare, prevents them from becoming so sick they cannot work.

It’s possible to argue that we, we the citizenry, have the rule of law, health care, transport and so on because we think they all benefit us, the citizenry. At which point any benefits to business seem fairly trivial. We also seem to rather like the things that business produces so, again, that they benefit as well seems unobjectionable.

But there is still that argument over how these things are provided. So, which is better - in quality - public health care or private? Public schools or state ones? The British experience is not that that which is tax provided is better now, is it?

So, if we’ve managed to understand Owen’s argument correctly it’s that business must pay more tax because the state provides things expensively and badly. Which is not, we think, one of the most convincing arguments ever put forward.

How excellent, proof that we're not going to run out of metals

People have been telling us for at least 50 years now - the Club of Rome and all that - that we’ll run out of metals within 30 years. The mistake here being that people look at mineral reserves and say they will run out. Which they will, given that the best colloquial translation of the technical phrase “mineral reserves” is the minerals we’ve prepared for use in the next 30 years. That is not, though, the end of the story. For those who understand the phrasing, or even the industry, know that reserves are things that are made, created, by human effort.

Near no environmentalists wanting to understand this point. Except, now, when we talk about fossil fuel reserves, they are making exactly this point:

Oil, gas and coal will need to be burned for some years to come. But it has been known since at least 2015 that a significant proportion of existing reserves must remain in the ground if global heating is to remain below 2C, the main Paris target. Financing for new reserves is therefore the “exact opposite” of what is required to tackle the climate crisis, the report’s authors said.

There we have it. Mineral reserves - and in this there is no difference between fossil fuels and metals - are things that are created through human effort and the expenditure of resources on their creation.

Therefore the debate over what we can use in the future is not bound or limited by what reserves are but by what we can turn into reserves by making that effort. As we’ve pointed out at book length before now those limits are some tens of millions to billions of years in the future. Or, as we might put it, recycling’s a fine thing but we don’t have to do it because we’re about to run out.

We can't help thinking there might be a connection here Polly

Polly Toynbee tells us that:

The next few years will be a carbon copy of post-2010 austerity, with a massive extra 8% cut to most public services – worse this time for coming on top of the last lost decade and the damage done by this crisis.

That may be a good idea, may not be, that’s not the point we wish to, umm, point to. Rather:

No one thought the economy would plummet by an unthinkable 10%,

That’s the damage that has been done by this crisis. There is 10% less of everything. That’s what the economy is, that everything, and a fall in GDP of 10% really is saying that all production, or all incomes, or all consumption - any one of the three equalling either of the other two - have fallen by 10%.

If we devote that same portion of everything we have to those public services then spending upon them should fall by 10% that is. As it happens the prediction - threat according to Polly - is that such diversion of resources will only fall by 8%. That is, there will be a rise in the portion of everything we devote to such things.

Which we can prove by looking at it the other way, the tax burden is predicted to rise by percentage points of GDP over the same period. That is, given those very numbers that Polly presents us with, far from having cuts in the public sector we are expanding it, we are spending a greater portion of everything we have upon them.

We don;t think we ought to be but then again that’s another point to be making.

We would regard this as a stunning victory ourselves

We do not mean to even imply, let alone state, that all economic policy in 2020 was entirely and wholly wonderful. We would however insist that this is a pretty good outcome:

Half of British workers had a real-terms pay cut in the year to autumn 2020, despite official figures showing the fastest earnings growth in almost two decades, research by the Resolution Foundation suggests.

The thinktank said official figures on average weekly earnings had been “hugely disrupted” by the large number of workers furloughed, and that the headline rates were “too good to be true”.

Data showing average weekly earnings growth of 4.5% in late 2020 – its highest level since 2002 – did not reflect how pay packets had changed, it said, and was distorted by changes in the makeup of the workforce, with many in low-paid work losing jobs during the pandemic.

The foundation said its research indicated that the median annual pay rise was 0.6% last autumn, which once inflation was taken into account meant half of workers had experienced a 0.2% pay cut over 12 months.

It’s worth reminding ourselves that UK GDP fell 9.9% in 2020. Yes, we know that the year to autumn 2020 and the calendar year 2020 are not exactly the same time period.

GDP is, by definition, all incomes. So, we’ve a 10% drop in aggregate incomes and if the biggest complaint is that half of workers suffered a 0.2% pay fall then we’d regard that as something of a victory. The assumption must be that the fall in income was concentrated among the higher income groups.

It reminds us rather of George Monbiot’s reaction to Fukushima. Absolutely the worst possible disaster happened, three reactors melt down as a result of an earthquake and tsunami, and the number of deaths from the nuclear part of that accident seems to be zero. We should therefore conclude, with George, that nuclear has its merits.

We have the worst economic year for over three centuries and the complaint is a 0.2% fall in certain incomes? What the heck do we have to do to be able to declare a win here?

Is Council Tax fair?

Is it fair that a little old lady, in her family home, impoverished and using few council services, pays far more council tax than a family of large wage earners in social housing and using most of the services? Council tax is based on an out-of-date assessment of the value of one’s home. It is based on the daft assumption that the wealthy live in expensive properties and the deprived in cheap accommodation. Moving to local income tax, as has been long discussed, would be a start.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies concluded that it would help accountability and should be a flat rate. The bureaucracy should not be a problem as it could be based on the same assessments as the HMRC uses for national income tax. That would save the need for periodic property valuations. Other countries use sales tax (USA) or VAT (Canada) to provide local government revenue.

Another daft feature of the UK system is the reliance by local government on Whitehall handouts. The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) employs about half of its 4,609 people devising myriad arcane ways of using national tax revenue to induce local government to do what it wants. Nanny knows best. Perish the thought that local governments should do what their locals want. The simple truth is that the taxpayers’ money could go straight to local government in the form of local income tax, or VAT receipts or whatever, and the MHCLG should be abolished. If Robert Jenrick pulled the plug on his department, greater things would await him.

Councils have not been helped by the government’s financial pressures since 2008. When choosing between restraining one’s own spending or someone else’s, it is no surprise Whitehall has preferred the latter. In 2009/10 MHCLG provided two thirds of local government expenditure. By 2018/19 it was less than half. The squeeze on local government spending partly accounts for the increasingly poor provision of adult social care which is mostly funded by MHCLG.

What MHCLG wants to achieve, in its redistribution of our money to local authorities, is far from clear. It could be seeking equality in the sense of funding all councils at levels they can provide equivalent services or rewarding those that provide the best taxpayer value or gerrymandering or giving preference to particular services such as social care. This is a difficult area: in an ideal world, all councils would be equally efficient and provide equivalent services, bearing in mind the different needs of affluent and deprived areas and costs, e.g. the annual costs of carers. But this is not an ideal world: Wandsworth’s Band D council tax is £845 compared with £1,959 in their neighbouring Richmond and £2,057 in the only slightly further Kingston. The services are not that different and the rates of council tax are after MHCLG have done whatever harmonisation they may do.

Devolving expenditure to units closer to the taxpayer is supposed to improve accountability and taxpayer value, and ensure that expenditure is more closely aligned with what the locals want. In practice, Wandsworth aside, MHCLG does not do any of those things. And there are other ministries that should also be devolved, notably Education and Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Why should a Whitehall committee decide that a Bradford theatre was more worthy of support than one in Leeds, or vice versa. We have much to learn from how the Swiss central government and cantons exercise their roles.

There are two main explanations for the variation in councils’ competence: governance and voter apathy. With two levels of local councils, e.g. County and District, there are not enough high grade councillors to go round. A start could be made by creating more Unitaries. Norfolk voted against that purely because turkeys don’t vote for Christmas. London is a special case. The central bureaucracy has grown by 33% under Sadiq Khan up to 2018. Whilst a few things need London-wide policies, the lion’s share of London government should be undertaken by the boroughs – perhaps with some mergers. After all, London managed quite well over the 14 years from Margaret Thatcher’s abolition of the Greater London Council in 1986 to Tony Blair’s reinstatement as the Greater London Authority in 2000.

The other reason for poor council performance is public indifference. The media fully covers national politics but gives scant attention to local government. The demise of local media is partly to blame. Apart from sideshows, like toppling statues and councillors awarding themselves higher than inflation rises in expense allowances, there is little of interest to report. Accountability needs news to be created.

The Audit Commission was created in 1983 to keep local council books in order but by 2015 the government decided it had become “wasteful, ineffective and undemocratic” and closing it would save £1.2bn over 10 years. Auditing was put out to the private sector. The trouble is that auditors (and I used to be one) are nice to their clients on account of wanting to keep the business. They are professional but prefer to rectify problems discreetly. The National Audit Office (NAO) operates far more openly. It has two branches, audit and taxpayer value, and its reports to the Public Accounts Committee pull no punches. We need a Local Audit Office (LAO) that operates in much the same way, reporting to audit committees that are wholly independent of their councils. The LAO reports need to be publicised locally.

The Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman claims to provide statistics on councils’ performance that are only about how complaints were dealt with. IMPOWER collects data enabling councils to compare their performance with similar local authorities. Unfortunately, confidentiality is part of the deal (to acquire the data) so the councils’ electorates are none the wiser.

Some issues do get local media attention. In some seaside areas and in Wales, second homes is one such issue. Second homes in these areas are alleged to deprive the less affluent locals, farm workers for example, from buying starter homes and to raise house prices in general. Second homes are often rarely visited so village schools, post offices, shops, and pubs close. In short, villages die. Worse still, the owners can claim they are making the second homes available as holiday rentals (they do not actually have to rent them out) and thus avoid council tax and also the income is below the business rates threshold. This minor scandal has been drawn to the attention of MHCLG but apparently they do not have enough staff to deal with it. It would take them 10 minutes to draw up a regulation making local councils responsible for sorting it out.

Two final caveats: if local income tax becomes the main revenue for local authorities it should be progressive, like national income tax, and not a flat rate. Local authorities should not be allowed to beat their budgets by borrowing. Managing inflation and protecting our currency are matters for the Bank of England and HM Treasury.

The second homes case history illustrates the need to devolve local matters to local councils and make local taxation both rational and fair.

Reasons for optimism - nanotechnology

Nanotechnology has already transformed many materials, and is in the process of tailor-making many more to our specifications. It is a reason to be optimistic that newly developed materials will be enabling us the achieve things thought impossible less than a generation ago.

It is basically a technology that manages to manipulate the molecular structure of materials to alter their properties. A nanometre is one-billionth of a metre, about 80,000 times thinner than a human hair. This is the scale on which atoms and the molecules they make are measured, and technology at this level involves controlling individual atoms and molecules. It has already enabled revolutionary applications.

New forms of carbon have been developed, including nanotubes and nanopillars that are used to make solar panels more efficient. Graphene, a single atom thick, is harder than steel and lighter than aluminium. So-called “first generation” passive nanomaterials are used in surface coatings to allow golf balls to fly straighter and to enable windows to be self-cleaning. Bandages infused with silver nanoparticles enable cuts to heal faster. Clothing impregnated with nanoparticles has been developed to last longer, stay cleaner, and enable people to keep cool in hot weather.

Steel embedded with nanoparticles makes possible beams that are lighter and thinner, yet stronger. A nanocomposite coating for oil industry pipes makes them more resistant to corrosion. Nanotechnology makes its mark in electronics, energy, the food industry and in air and water purification.

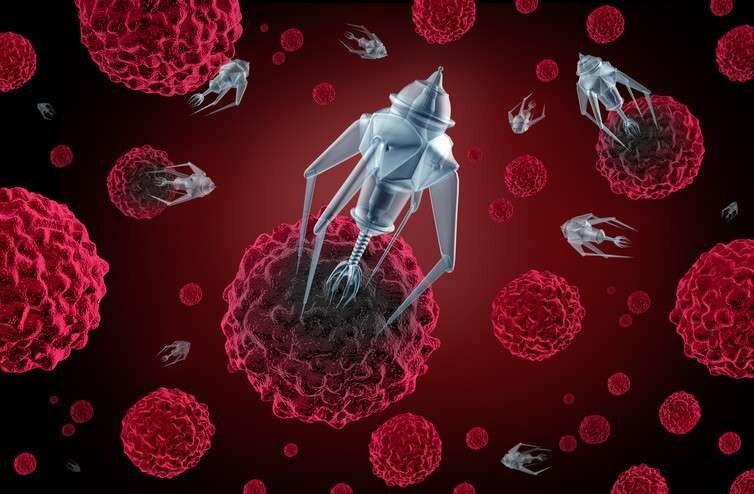

One of the most exciting and promising applications is in the field of biomedicine, where it plays a role in tissue engineering, replicating with nanoparticles the body’s cell structure in order to help it repair damaged tissue. It is playing an increasing role in biosensors to give early warning of developing dangers, and in accurately targeting drug delivery to precise locations. Some nanomaterials are being specifically designed to seek out and destroy cancer cells without damaging healthy ones. This raises the prospect of the elusive ‘cure for cancer’ long thought impossible.

Optimism about nanotechnology has been tempered by concerns about possible hazards brought about by absorption of nanoparticles into the body. It has led to safety procedures being incorporated into the manufacture and use of nanoparticles, and into monitoring of their possible effects. One alarmist notion was that self-replicating nano machines would consume the environment and turn the entire planet into a “grey goo.” Prince Charles raised this prospect, calling on the Royal Society to investigate the risks, to the puzzlement of UK nanotechnologists unaware of that particular scenario.

Some progress in nanotechnology breakthroughs now goes unannounced, lest predatory NGOs use it in scare stories to raise funds with, as they did with genetically modified organisms, causing politicians to impose arbitrary controls. While it makes sense for nanotechnologists to shun the limelight, it does mean that progress is slower than it would be if it were all in the public domain.

It does mean that some of the breakthroughs will be announced suddenly when complete, rather than while still under development. We can look forward to periodic unveiling of advances in nanotechnology that give us access to better materials, better medicine, and which improve many of the things we routinely do by enabling us to do them better.

Some statistics just aren't all that surprising

Torsten Bell tells us that:

First, big cities have more than their share of poor families – overall, Londoners have below average disposable incomes.

Well, not so much really. Londoners have below average disposable incomes after housing costs and above before. Which, given that housing in London is more expensive than it is in other areas of the country isn’t, in fact, all that much of a surprise.

However, this is also important. For the usual measures of inequality across Britain keep telling us - and thus the levelling up mantra - that Britain is unequal across geography. Which is measured by the pre-housing costs measures. But if housing costs different amounts then inequality, across that geography, is lower than generally measured, isn’t it?

This extends further as well. The costs of near everything vary around the country - that first rural experience of London’s beer prices usually does bring an outburst of guttural Anglo Saxonisms.

Britain, by the only measure that can possibly matter - inequality of consumption - is very much less unequal than is generally assumed or measured. Therefore, of course, we need to do very much less about it.