This posting goes through the Bank of England’s leverage ratio stress test using an improved version of the leverage ratio to replace the one used by the Bank: it uses CET1 capital in the numerator instead of the looser and more gameable Tier 1 capital measure used by the Bank. Results show that the UK banking system performs extremely poorly by this stress test when assessed against the fully implemented leverage ratio requirements possible under Basel III, and even worse when assessed against minimum leverage ratio standards coming through in the United States and those recommended by experts.

In the previous posting, I examined the outcomes of stress tests that use the ratio of banks’ Tier 1 capital to leverage exposure as their capital adequacy metric. However, the use of Tier 1 capital in the numerator of the leverage ratio is problematic: Tier 1 capital is the sum of Core Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital plus Additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital, and AT1 includes hybrid capital instruments such as Contingent Convertible (CoCo) instruments which are of unreliable usefulness in a crisis. Including these in our capital measure is undesirable because it might overstate the capital available to support a bank in a crisis and so undermine the principal purpose of any core capital measure.

We therefore need a more prudent capital measure and a natural choice is CET1 without any additional, softer, capital. Roughly speaking, CET1 approximates to Tangible Common Equity (TCE) plus retained earnings, accumulated other income and other disclosed reserves. [1] The ‘tangible’ in TCE means that it excludes intangible items such as goodwill and Deferred Tax Assets, and the ‘common’ means that it gives a measure of common share capital (i.e., shareholder capital stripped of more senior capital instruments such as preferred stock and other hybrid items). Of the measures available (and unfortunately, TCE is typically not available) CET1 is the best capital because its component elements are the most fire-resistant and hence most deployable in the heat of a crisis. To quote Tim Bush, CET1 is:

the plain old fashioned accounting shareholder interest. It's what bears the first loss, pays divs, and is what has to be recapitalised. It also excludes goodwill [and any other intangibles and] any expectant income and books all expected losses. [2]

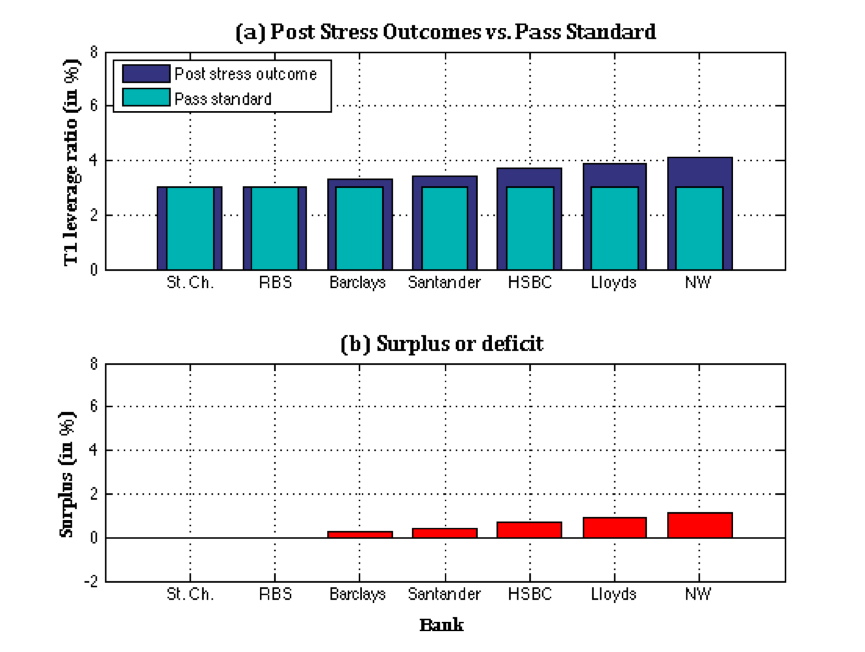

Now define the CET1 leverage ratio as the ratio of CET1 capital to leverage exposure. If we take the outcomes of the Bank’s stress test applied to the CET1 leverage ratio and take the pass standard to be the potential maximum required minimum leverage ratio under fully implemented Basel III, then we obtain the outcomes shown in Chart 1:

Chart 1: Stress Test Outcomes Using the CET1 Leverage Ratio with the Potential Maximum Basel III Pass Standard

Notes to Chart 1:

(a) Author’s calculations based on information provided by the Bank of England’s ‘The Financial Policy Committee’s review of the leverage ratio” (October 2014) based on the assumption that the pass standard is the potential maximum required minimum leverage ratios under fully-implemented Basel III.

(b) The outcome is expressed in terms of the CET1 leverage ratio post the stress scenario and post any resulting management actions. These data are obtained from Annex 1 of the Bank's stress test report (Bank of England, December 2015).

It is fair to say that if the previous outcomes were disastrous, these are positively dire. The average outcome is 3.1%, the average pass standard is 4.2%, the average shortfall is over a hundred basis points and every single bank fails the test by a comfortable margin. By this test, the entire UK banking system is well and truly below water.

But it gets worse.

One problem is that reported CET1 values can be inflated by at least three different factors. Briefly:

- The reported CET1s are based on IFRS accounting standards, and a key component of CET1 is retained earnings, the reported values of which are likely to be inflated because IFRS allows banks to inflate the underlying asset values. [3]

- The regulatory definition of CET1 endorsed by Basel III involves an awkward ‘sin bucket’ compromise by which various items of softer capital (such as Deferred Tax Assets and Mortgage Servicing Rights) can be included in reported CET1 provided they account for no more than 15% of total reported CET1. [4]

- The CET1 values reported here are book values and market values will typically be less. Thus, ‘true’ CET1 values can be considerably lower than those reported in the Bank of England’s stress test report.

The reported capital ratio is inflated further by a downward bias in the reported leverage exposure, which is the denominator in the leverage ratio. This downward bias is another long story. In theory, the leverage exposure is meant to take account of off-balance sheet items that would not show up in traditional exposure measures such as total assets. However, the regulatory leverage exposure measure is a highly compromised measure that is the result of a lot of behind the scenes lobbying by banks keen to keep their measured exposures down, not least in order to minimise their resulting capital requirements. Given (a) that off-balance-sheet items considerably exceed on-balance-sheet ones and (b) that accounting netting rules tend to hide a great deal of financial risk, if only because many supposedly hedged positions often fall apart in a crisis, and (c) that we know that banks are riddled with major data quality problems, then we would expect any half-decent exposure measure to be much greater than, say, reported total assets. However, they are not. In fact, when I looked into this matter, I was astonished to discover that the leverage exposures of UK banks are not only of the same order of magnitude as their balance sheet total assets, but are sometimes even lower. For example, the reported 2015Q3 leverage exposure for Lloyds was only 88% of its reported total assets. So once again, we have a downward bias in the leverage ratio numbers and no real way in which we can assess what the extent of that bias might be. However, whatever this bias might be, we can reasonably infer that it must be large.

We should also note that the pass standard assumed in the test reported in Chart 1 is by no means a high one and the Federal Reserve, for one, is already preparing to impose even higher minimum leverage ratios. In April 2014, the Fed finalized a set of ‘enhanced’ Supplementary Leverage Ratios (SLRs) on the 8 U.S. global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and their insured depository institutions. These are supplementary requirements in addition to those required under Basel III. As part of this requirement, the U.S. G-SIBs will have to meet a 5% SLR at the holding company level and a 6% SLR at the bank level, and are due to come into effect on January 1, 2018.

Well, to spell out the obvious: if the UK banks perform badly against a pass standard equal to the maximum potential standard under fully implemented Basel III, then they would perform even worse when assessed against the Federal Reserve’s higher standards.

There is also the question of what the required minimum leverage ratio should be, i.e., as assessed from first principles. Curiously, this is one of the few subjects in economics and finance where there is a considerable degree of consensus among experts – and their view is that minimum standards should be much higher than they currently are. We are not talking here about a couple of percentage points, but a minimum that is potentially an order of magnitude greater than current minimum capital requirements anywhere in the world. There is of course no magic number but what we want is a minimum requirement that is high enough to remove the overwhelming part of the risk-taking moral hazard that currently infects our banking system. As John Cochrane put it: it should be high enough until it doesn’t matter – high enough so that we never, ever again hear the call that banks need to be recapitalized at public expense.

This consensus was reflected in an important letter to the Financial Times in 2010, in which no less than 20 renowned experts – Anat Admati, Franklin Allen, Richard Brealey, Michael Brennan, Arnout Boot, Markus Brunnermeier, John Cochrane, Peter DeMarzo, Eugene Fama, Michael Fishman, Charles Goodhart, Martin Hellwig, Hayne Leland, Stewart Myers, Paul Pfleiderer, Jean-Charles Rochet, Stephen Ross, William Sharpe, Chester Spatt and Anjan Thakor – recommended a minimum ratio of equity to total assets of at least 15%, and some of these wanted minimum requirements that are much higher still. Independently, John Allison, Martin Hutchinson and yours truly have also called for minimum capital to asset ratios of at least 15%, Allan Meltzer recommended a minimum of 20% for the largest banks, Admati and Hellwig recommended a minimum at least of the order of 20-30%, Eugene Fama and Simon Johnson recommended a minimum of the order of 40-50%, and John Cochrane and Thomas Mayer have suggested 100%.

By these minimum standards, the UK banking system is not so much underwater as stuck as the bottom of the ocean.

So what can we conclude from these stress test exercises?

Without a shadow of a doubt, the entire UK banking system is massively undercapitalised even under the relatively mild adverse ‘stress’ scenario considered by the Bank of England.

End Notes

[1] For a more complete definition of CET1 capital, see Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) “Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems” (Basel Committee, June 2011), p. 13.

[2] Personal correspondence.

[3] These and other problems with IFRS accounting standards are explained further by Tim Bush, “UK and Irish Banks Capital Losses – Post Mortem,” Local Authority Pension Fund Forum, 2011, and Gordon Kerr, “The Law of Opposites: Illusory Profits in the Financial Sector”, Adam Smith Institute, 2011.

[4] For more on this subject, see Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems," revised version June 2011, pp. 13, 21-26 and Annexe 2, and Thomas F. Huertas, Safe to Fail: How Resolution Will Revolutionise Banking, Palgrave, 2014, p. 23.