Central banks cause low interest rates, but not by lowering interest rates

The Bank of England slashed its discount rate ('Bank Rate') to 0.5% in its 5th March 2009 meeting in response to the growing recession, hoping to stimulate demand. Its discount rate is the rate it lends out to commercial banks—and a lower rate is believed to raise economic activity, whether through expectations, extra nominal income or increased lending. It has left it there ever since, and indeed, because of the 'Zero Lower Bound' on interest rates it has turned to other tools to try and bring about an economic recovery—a recovery which is only just setting in properly. When the Bank moves its key policy rate, commentators talk about it hiking or cutting interest rates; on top of this, we've seen extremely low effective interest rates in the marketplace; together this makes it reasonable to believe that the central bank is the cause of these low effective rates.

There are lots of reasons to doubt this claim. In a previous post I pointed out that the spreads between Bank Rate and market rates seem to be narrow and fairly consistent—until they're not. I made the case that markets set rates in an open economy. And I argued that lowering Bank Rate or buying up assets with quantitative easing (QE) may well boost market rates because they raise the expected path of demand, the expected amount of profit opportunities in the future, and thus investment.

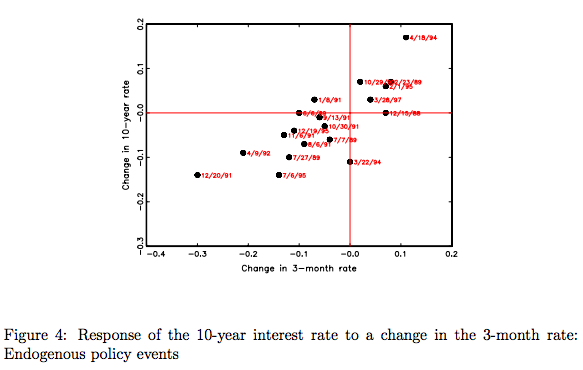

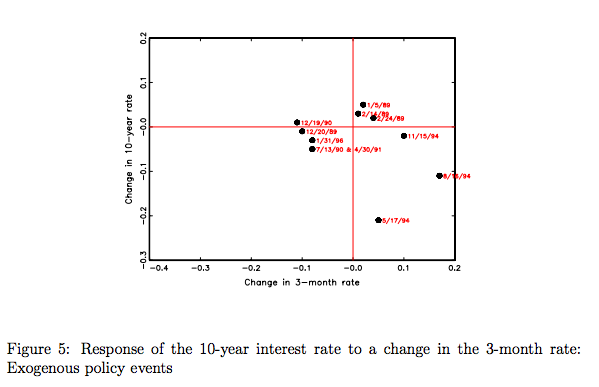

Since then I came across an elegant and compelling explanation of exactly why this is. In a 1998 paper, Tore Ellingsen and Ulf Söderström show that this is because some monetary policy changes are purely expected and 'endogenous' responses to economic events, whereas some monetary policy changes are unexpected 'exogenous' changes to the central bank's overall policy framework (like raising or lowering the inflation rate that markets believe they really want).

When changes are expected, market rates keep a tight spread around policy rates; when changes are a surprise, cutting Bank Rate actually results in higher interest rates in the marketplace.

To identify which changes were exogenous (surprises) and which changes were endogenous (expected) Ellingsen and Söderström looked at market commentaries in the Wall Street Journal the day after policy events—where the Fed decided whether to change or maintain its current policy rate. When traders they interviewed were surprised or disappointed by the move (or lack of move), they judged it exogenous—when traders explained the Fed's move in terms of changes in economic data they judged it endogenous.

This neatly explains why raising Bank Rate would not shut off bubbles (as an aside: a recently-published paper finds that tight, not easy money, is more closely associated with bubbles) and house price booms and so on. Cutting Bank Rate would raise market rates if it changed markets' perceptions of what target the Bank of England is working towards (i.e. made them think it wanted higher inflation). Conversely, if the Bank had decided not to look through high supply-driven inflation, and thus surprised markets by running tighter than expected policy, this would have been likely to push rates even lower.

The best way to get rates back to normal territory, thus incentivising firms to economise on investment projects and put cash into only the very best, is to make sure the economy doesn't suffer the effects of what Hayek called a 'secondary depression'. And the best way to ensure that is to implement something we might call a 'Hayek Rule' after the monetary policy he proposed—stabilising MV (the money supply x velocity, equal to aggregate nominal income). Recent work has shown that we get less creative destruction and capital reallocation in slumps as opposed to healthy growth periods.

Firm expectations now mean that setting this at zero, as he proposed, would have a very costly intermediate period while firms reset their plans—setting it at the rate consistent with 2% inflation (roughly 5%) would be more appropriate. Perhaps in the long run it could come down. But without a stable macroeconomic environment, capitalism cannot create the wealth that makes it so widely and dynamically successful.