Northern Ireland does something very stupid about prostitution

It's always a little difficult for an Englishman, even one with an extra Irish citizenship (as your author does), to criticise an Irishman for being stupid. That century or more of their being the butt of bad jokes about imbecility creates a certain sensitivity to such an accusation. But this is still flat out a stupid thing to be doing:

Paying for sex is to be banned in Northern Ireland after members at the Stormont assembly members backed the move in a landmark late-night vote.The proposal to outlaw purchasing sex is among a number of clauses contained in a bill aimed at amending Northern Ireland’s laws on trafficking and prostitution.

Paid-for consensual sex is currently legal in Northern Ireland though activities such as kerb crawling, brothel keeping and pimping are against the law. The proposed ban is similar to the model operating in Sweden.

The human trafficking and exploitation bill was tabled before the assembly by Democratic Unionist peer Lord Morrow.

Trafficking and exploitation are already illegal: making voluntary transactions between consenting adults illegal will not make their incidence any less. Far from it, driving currently legal activity underground will produce more of those already illegal activities rather than less.

At the grander level this is horribly illiberal: the touchstone of any possible liberal society being that consenting adults, when their activities do not harm any non-consenting people, animals or things, get to do what they want. A society that decides to regulate adult sexual activity is not and cannot be described as liberal. It can be anything from Puritan to authoritarian but liberal it cannot be. And we've made hugely welcome strides in the direction of that liberality over the decades: for example, from the illegality of homosexual activity to the widespread acceptance societally of same sex civil partnerships. Plus, of course, the more general idea that what people do in their sex lives is up to them. Quite why anyone thinks that the intercession of a £50 note into the proceedings makes any difference is extremely difficult to fathom. It's still the entirely voluntary playing out of the Tab A and Slot B scenario that we all agree consenting adults are entirely at liberty to perform as they wish.

At the more detailed public policy level there will obviously now be calls that England should follow suit. To which the correct answer is, as above, no it shouldn't. But even if you don't find a defence of adults being allowed to be adults convincing there is another. Which is that we really should take advantage of this devolved administration stuff to wait and see what happens. It'll take a few years for this change in the law to filter through to human behaviour. Time which could usefully be spent actually looking at what happens. Only after we've done that will we know what does actually happen: and only once we do know what happens that's the first time that we can or could usefully discuss whether it's a good idea or not.

It's definitional that of course consenting adults should be allowed to consent. But even if you don't believe that let's wait and see what actually happens here, eh?

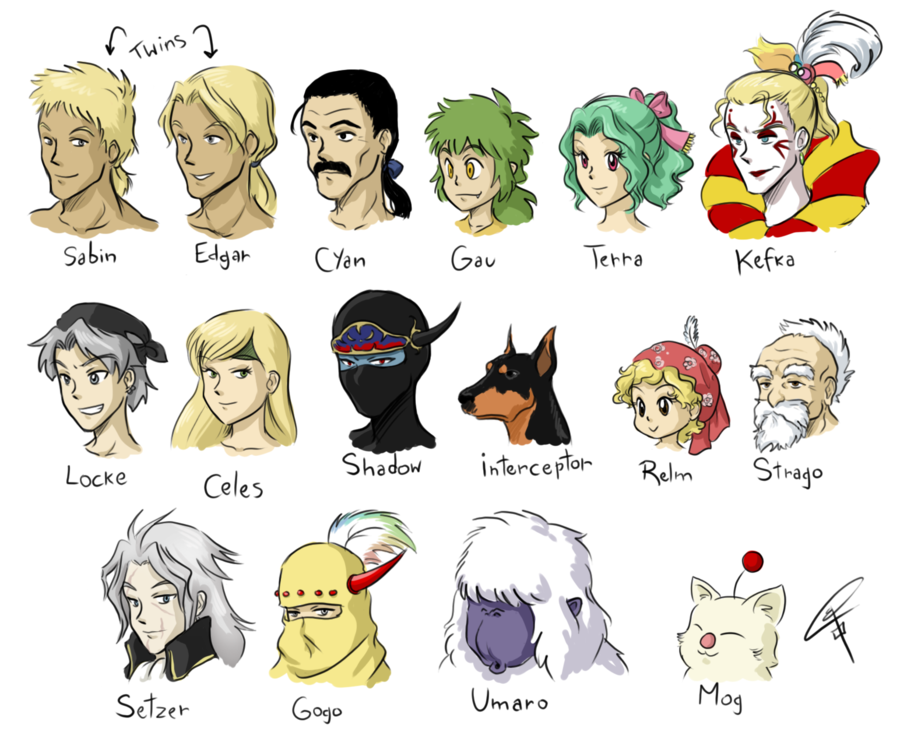

Is Gamergate a classic case of left-wing infighting?

I published a 'think piece' on gamergate over at the research side of the website yesterday. I argued that the pro-gamergate side was likely to lose because the left usually wins (for good or bad) on cultural issues:

Gamergate is one of the most interesting cultural issues that has appeared in years. It is a rare time that the losing side of the culture war has put up a good fight. But the anti-gamergate side will win, because Progress always wins. I’ll try and give a concise guide to gamergate, what’s at stake, where it came from, and why exactly it is that it will lose.

I read another good post on it from Cathy Young over at realclearpolitics—she made a different point to mine, trying to stress how it was not reasonable to characterise much of the movement as anti-women or misogynist, but simply taking an alternative (and she believes, valid) approach to improving the lot of women in gaming:

There are valid concerns, shared by at least some GamerGate supporters, about sex-based harassment in gaming groups and stereotypical portrayal of female characters in videogames. Unfortunately, critics of sexism in videogame culture tend to embrace a toxic brand of feminism that promotes antagonism, grievance, and intolerance of dissent, not equality or empowerment.

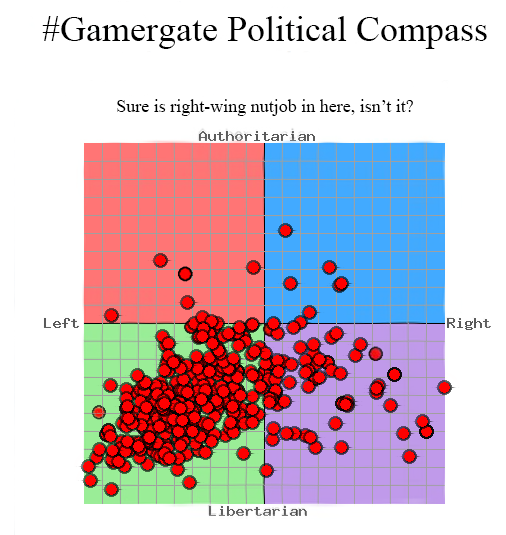

When I posted my piece on twitter I asked for constructive criticism, and one good point that was made is that, at least according to their own views of themselves and their results on political compass tests, gamergaters tend to lean left.

This makes me think that gamergate might be best characterised as a case of leftist infighting, but this time between Murray & Herrnstein's 'cognitive elites' that make up social justice anti-gamergate journalism and the broader constituency of more 'normal' pro-gamergate leftists holding more traditional leftist views. An open front in the war between New and old versions of what justice consists in.

This fits with my anecdotal experience that it is those (like Richard Dawkins) who are or have been associated with the left that experience most of their ire when they state or are suspected of having unacceptable views. As ever it's interesting to look at the parallel with religion, which abhors apostates much more zealously than infidels.

And it also fits with the modern left's de facto focus on race, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability as opposed to their previously overwhelming concern with economic exploitation or justice. As I said in the think piece:

Bear in mind that although social justice advocates do care about wealth disparities, this is far from their main concern, at least in terms of how they allocate their time. For example, insufficiently pro-transgender feminists will arouse large campaigns stopping them from giving lectures at many universities, while libertarian capitalists can speak freely. This is why I have argued that social justice is (a) a facet of neoliberalism, and (b) an artefact of the cognitive elite’s takeover of society. This is what makes the modern social justice movement so different.

This ends up working quite well for the ASI: we are quite comfortable with social progress as long as it allows for liberal economic policy, and only tend to object when social progress conflicts with more important goals such as free speech.

The Daily Mail's actually right about NHS Wales here

It's ever so slightly uncomfortable top be agreeing with the Daily Mail here as they're being so nakedly politically partisan about the NHS, the Labour Party and Wales. However, it should be said that they're actually correct in what they're saying:

Today this paper publishes the first part of an explosive investigation which blows away Ed Miliband’s claim that his party can be trusted with the NHS.Indeed, there is no need to imagine how the service might perform under Labour. For the evidence is before us in Wales, where the party has had full control of the funding and management of health care since devolution 15 years ago.

As Guy Adams exposes on Pages 8 and 9, a picture emerges of a Welsh NHS on the point of meltdown, in which the wellbeing and often the lives of patients are routinely sacrificed on an altar of Socialist ideology.

The Welsh NHS has of course complained and the Mail's response to those complaints is here.

We here at the ASI might not have put all of this into quite such politically loaded terms but the basic critique is correct, in that NHS Wales performs less well than NHS England. And we also know why this is so: NHS Wales has not adopted the last few rounds of a more market based structure as NHS England has. We've also known this for some years:

Some would argue that the drops in waiting times were driven by increased spending, rather than targets, patient choice and hospital competition. Hence the fears sparked by the McKinsey report of the possibility of massive cuts in services. However, money alone cannot explain why waiting times have dropped and equity has improved in England. During the same period that we examined waiting times in England in our study, Scotland and Wales, which both explicitly rejected market-driven reforms, have spent more per patient but have seen much smaller decreases in waiting times.

The more market orientated NHS England is both more equitable and more efficient than the less market orientated NHS Wales and NHS Scotland. Indicating that market based reforms are a pretty good idea: whatever that socialist ideology (although to be fair about it, it's really just an innate conservatism allied with the traditional British dislike of anything that smacks of trade rather than a principled socialism) might have to say about it.

The tax system is the biggest barrier to growth

Outside of academic papers that too rarely see the light of day, most "research" is unremarkable in its optimism about the state of entrepreneurship in the UK. That’s why the RSA’s Growing Pains: How the UK became a nation of “micropreneurs” caught my eye. It paints a stark picture. The UK, according to the report, has become a nation of micro businesses, while the proportion of high-growth businesses has plummeted: “UK businesses are becoming increasingly micro in size – reducing the overall potential for economic output and future growth, and increasing the economy’s reliance on a relatively small number of larger businesses.”

Since 2000, the proportion of businesses classified as micro (0-9 employees), as a share of all UK businesses has grown from 94.3 per cent of all private sector companies to 95.4%. This represents an additional 1.4 million micro firms and an increase over the same period of 43%.

“At the same time, the proportion of high-growth enterprises has declined sharply, falling by more than a fifth in the majority of regions since 2005.”

Although the number of high-growth firms is expected to rise over the coming years, the report cautions optimism: “performance is expected to remain below 2005 levels in all regions except London”.

So how can we solve the problem? According the entrepreneurs, the tax system (44%) is the biggest barrier to growth – ahead of a lack of bank lending (38%) and the cost of running a business (36%).

Another problem highlighted by the report is that entrepreneurs don't know what the government is up to:

“Around three-quarters (73%) of small business leaders also say the Government must make it easier for SMEs to access the right information and support for growth. While several of the Government’s recent incentives to support SMEs are designed to address the top-cited barriers, perhaps this information is not reaching the people who need it the most.”

Two polices are put forward in the conclusion to help entrepreneurs. First, “continued reform of the apprenticeship scheme could help micro firms to grow out of this business size category”. Second, “more tax relief like the National Insurance holiday could also pay real dividends.” It would be worth exploring the former in detail (something I plan to work on), but I don’t think another NI holiday goes nearly far enough: Employers' National Insurance should be scrapped entirely. And no just for small businesses.

Being an entrepreneur is tough. As the report points out, “the majority (55%) of new businesses don’t survive beyond five years.” Scrapping Employers' NI is the logical place to start.

Philip Salter is director of The Entrepreneurs Network.

The ECB is fiddling while Europe burns

If not quite burning yet, the eurozone is kindling. For once, most people agree why: money is very tight. The central bank's interest rate is low, yes, but this is not a good measure of the stance of monetary policy. What matters is the interest rate relative to the 'natural' interest rate - ie, what it would be in a free market. It's difficult to know what this natural rate is (as Hayek would tell us) but we can look at things like nominal GDP and inflation to help us guess. Both are way, way below levels that the market is used to. Deflation is back on the menu.

As Scott points out, whatever you think about the American or British economies since 2008, the Eurozone looks like a case study in central bank failure:

The eurozone was already in recession in July 2008, and eurozone interest rates were relative high, and then the ECB raised them further. How is tight money not the cause of the subsequent NGDP collapse? Is there any mainstream AS/AD or IS/LM model that would exonerate the ECB? I get that people are skeptical of my argument when the US was at the zero bound. But the ECB wasn’t even close to the zero bound in 2008. I get that people don’t like NGDP growth as an indicator of monetary policy, and want “concrete steppes.” Well the ECB raised rates in 2008. The ECB is standing over the body with a revolver in its hand. The body has a bullet wound. The revolver is still smoking. And still most economists don’t believe it. ”My goodness, a central bank would never cause a recession, that only happened in the bad old days, the 1930s.”

. . . And then three years later they do it again. Rates were already above the zero bound in early 2011, and then the ECB raised them again. Twice. The ECB is now a serial killer. They had marched down the hall to another office, and shot another worker. Again they are again caught with a gun in their hand. Still smoking.

Meanwhile the economics profession is like Inspector Clouseau, looking for ways a sovereign debt crisis could have cause the second dip, even though the US did much more austerity after 2011 than the eurozone. Real GDP in the eurozone is now lower than in 2007, and we are to believe this is due to a housing bubble in the US, and turmoil in the Ukraine? If the situation in Europe were not so tragic this would be comical.

There is a point here. Economic news, by its nature, tends to emphasise interesting, tangible, 'real' events over things like central bank policy changes (let alone the absence of changes).

Of course that can be deeply misleading. The stance of money affects the whole economy (at least the whole economy that does business in nominal terms, which is pretty much everything except for gilt markets), and the Eurozone is experiencing exactly the sort of problems that the likes of Milton Friedman predicted that tight money would create.

Overall, the Euro looks like the most harmful institution in the world, except perhaps for ISIS or the North Korean govt. It may be unsaveable in the sense that it will never really be an optimal currency area, but looser policy (which free banking would provide) would probably alleviate many of the Eurozone's biggest problems. Instead, what Europe has is the NHS of money – big, clunking and unresponsive to demand.

And the ECB seems wilfully misguided about what it needs to do. The only argument against this is that surely—surely—Draghi and co know what they're doing. Well, what if they don't?

Another exercise in rewriting economic history

It is just so fun watching people rearranging the historical deckchairs to make sure that their tribe looks good and that the tribe of their opponents can be portrayed as those nasty, 'orrible, people over there. And so it is with this latest from Ha Joon Chang:

First, let’s look at the origins of the deficit. Contrary to the Conservative portrayal of it as a spendthrift party, Labour kept the budget in balance averaged over its first six years in office between 1997 and 2002. Between 2003 and 2007 the deficit rose, but at 3.2% of GDP a year it was manageable.

Quite: in those first few years Blair and Brown held to the spending limits that had been suggested by the previous, outgoing, Tory government. On the basis that if anyone thought they were the spendthrift Labour party of old then they wouldn't get elected. So there was, in there, a period of a public sector surplus. It's only after the second election that they ripped up that idea of fiscal restraint and became that Labour party of old again. So "balance" over the six years is actually a couple of years of Tory policy then spend, spend, spend.

And a deficit of 3.2% a year might be manageable: except of course it wasn't, was it? But more importantly it is a grave violation of the precepts of Keynesian economics to be having a deficit of any sort at that point in the economic cycle. If we are to take Keynesian demand management seriously (we don't, but let us do so arguendo) then yes, there should be fiscal expansion in the slumps. But the counterpart to that is that in the boom there should be restraint: a surplus, not a deficit. This is not to pay off the previous debt, it's not to create the borrowing room to provide the firepower for that next slump. It's because demand management means that you temper the booms as well as the busts. Given that the middle part of the Brown/Blair Terror was in fact the tail end of the longest modern peacetime boom then the public accounts should have been healthily in surplus. In order to temper that boom.

Chang is doing an edit to history here, to show that his tribe is better than the other one. Given the circumstances of the time Labour really were sailor-type drunken loons going on a spree with the nation's chequebook and don't let anybody tell you different.

The mansion tax is theft, a bit at a time

Strange, is it not, how politicians never ask how they could cut their own spending, but only think about how they can raise taxes from other people. Mr Balls reckons he can raise £1.2bn from the tax, which he says would come in handy for the NHS, he reckons (though the emerging black hole in the NHS budget is much larger than that). How does he know? He says much of the tax would come from foreigners with big houses in London, but does not seem to know how many of them there are. No, as usual, it will be the Great British public who foot most of the bill, and not just the rich. Tens of thousands of homes in London will be caught by it, for example, where the average price in a 'prime area' will probably hit the £2m mansion tax threshold by the time of the 2015 election. And 'prime' includes areas like Battersea and Clapham, not just swanky Kensington and Chelsea.

There are already plenty of taxes on property. Not only is there the council tax, but there is stamp duty when you buy a house and inheritance tax when you give it to your kids. Now the plan is to add another, of perhaps £4,000 a year.

We all know what will happen. The tax will be imposed on properties of £2m, and over the years, thanks to (politician-created) inflation and (politician-created) planning restrictions, the cost of property will rise. More and more properties will be hit by the 'mansion' tax (yes, including broom cupboards in Kensington), just as more and more people now pay the 40% higher rate of income tax, which was originally targeted at the wealthy but is now paid by people like teachers and police officers.

And our tax (and subsidy) system is already highly progressive. Wealthier people pay higher taxes of many kinds, while poorer areas get subsidies through the local government finance system.

The mansion tax is theft, a bit at a time. There will be many people who happen to live in large houses but have little or nothing in the way of income (such as those on pensions) with which to pay the tax. Perhaps the house was their childhood home and they can't face moving. Moving is a strain even for the most robust of us. Ed Balls says, well maybe poorer people could defer the tax until they sell the house or pass it on after their death. But that makes the tax even more complicated - it is going to need a means test and a lot of extra bureaucracy, more lines on the tax form and all the stuff that has already got us in such an overtaxed bureaucratic pickle. This is a tax we could well do without.

Equal pay for equal work

A recent speech by Andy Haldane, the Bank of England's chief economist, sheds a good deal of light on the cost of living crisis and the union-led "Britain Needs a Payrise" campaign. Haldane points out how grim the recent situation has been for real wages in the UK economy:

Growth in real wages has been negative for all bar three of the past 74 months. The cumulative fall in real wages since their pre-recession peak is around 10%. As best we can tell, the length and depth of this fall is unprecedented since at least the mid-1800s.

But is this because employers have suddenly become selfish capitalists, whereas before they were paying workers out of the good of their heart? Or is something else at play?

Productivity – GDP per hour worked – was broadly unchanged in the year to 2014 Q2, leaving it around 15% below its pre-crisis trend level. The level of productivity is no higher than it was six years ago. This is the so-called “productivity puzzle”. Productivity has not flat-lined for that long in any period since the 1880s, other than following demobilisation after the World Wars.

We usually think that wages and productivity will be pretty closely related. Employers are unlikely to consistently pay above productivity, because they'd lose money. But equally, they'll be unable to consistently pay far below productivity (less the share needed to rent the capital involved) because in a reasonably competitive market firms will compete their workers away with more attractive job offers.

We might think this is particularly true at the low wage end of the market, because much less of low-skilled workers productivity is job specific. An accountant makes a very poor lawyer, and a civil engineer is not qualified to write code, but a worker in McDonalds will be similarly good at Burger King, or for that matter Waterstones, JR Wetherspoon, Lidl or most other relatively low-skilled areas.

So basic economic models suggest pay will track productivity. And what do we see on the macro level?

The deficit in pay tracks the deficit in productivity. Of course, the situation for public sector workers is a bit different—we actually measure their productivity mainly by inputs. If their pay goes up, their measured productivity goes up. It's hard to see how else we would do it. But the overall picture suggests that the real pay decline is down to a real productivity decline. We haven't moved away from equal pay for equal work—we've just had a big horrible recession and a sluggish recovery!

R&D's great but why a target for spending on it?

R&D's just lovely, it is, after all, how we develop the new technologies that are such an important part of economic growth. But we do hesitate a little bit when people start to say that we should have targets for spending upon something, whether it be R&D, poverty alleviation or education:

A "bold strategy” is needed to remedy weaknesses in Britain’s supply chain, according to the CBI, in a push to create 500,000 new jobs and boost the economy by £30bn.The CBI feels a long-term target of 3pc of gross domestic product for public and private sector spending on research and development would underpin a turnaround over the next decade.

It's all a bit never mind the quality, feel the width, isn't it? For it's not actually true that devoting more resources to something is desirable: what we want is more output of whatever it is from the resources that we do devote to that thing. We could describe this as being almost Stalinist: don't worry about how good each car is but just weigh how much steel we put into each one! Or, another way of making the same point is that GDP, the thing we use to measure economic growth, is actually measuring value added in the economy. Except when we come to talking about government of course. There we've no idea what the value added is so we just assume that the output is worth the value of the resources devoted to producing it.

That's not an assumption that holds true in the real world of course: and so it is and would be with R&D spending. How much we spend on it isn't the interesting or important point: how much cool new stuff and shiny shiny we get from spending on R&D is.

The report shows a lack of investment in research and development, along with a growing skills crisis, has weakened “foundation industries” such as plastics, metals and chemicals.

It is also calling for a change in research tax credits to help innovation and incentives to encourage more graduates to take science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) degrees.

Creating a national materials strategy to protect and enhance critical supply chain sub-sectors and doubling the budget of Innovate UK are among other measures in the CBI programme.

It all does smack rather of that old industrial planning, doesn't it, where success is measured by resources consumed rather than the value of the output.

Finally, as an aside, encouraging more people to take STEM degrees is very simple indeed. The employers of those who graduate with STEM degrees should increase the wage they pay to those with STEM degrees. Rather than demand that the State subsidise the creation of a willing workforce.

The terrible error of Naomi Klein

Naomi Klein tells us that the polluter must pay. Something that is both logical and true. Then she tells us that the fossil fuel companies must be made to pay for the damage that they do. Also logical and true:

Up until the early 1980s, that was still a guiding principle of environmental law-making in North America. And the principle hasn’t totally disappeared – it’s the reason why Exxon and BP were forced to pick up large portions of the bills after the Valdez and Deepwater Horizon disasters.

We might quibble about whether the damage was quite what was described or paid for but the basic principle is entirely fair. However, here comes the error:

The astronomical profits these companies and their cohorts continue to earn from digging up and burning fossil fuels cannot continue to haemorrhage into private coffers. They must, instead, be harnessed to help roll out the clean technologies and infrastructure that will allow us to move beyond these dangerous energy sources, as well as to help us adapt to the heavy weather we have already locked in. A minimal carbon tax whose price tag can be passed on to consumers is no substitute for a real polluter-pays framework – not after decades of inaction has made the problem immeasurably worse (inaction secured, in part, by a climate denial movement funded by some of these same corporations).

Assume, for a moment, that CO2 emissions are indeed causing damage. So, who is responsible for those emissions? Who is the polluter here who must pay?

When I drive to the shops it is me making the decision to do so, me making the decision to emit CO2 in gaining my supply of comestibles. I am therefore the polluter. That's why, if there is to be a tax on polluters it should be upon me, the polluter. Which is the entire point of a carbon tax that can be passed on to the consumers. It is we consumers who are the polluters which is why we should have that tax which falls upon the polluters.

This is the most appalling and most basic error by Klein. We do not consume fossil fuels because Teh Eeevil Corporations force them upon us. We consume them because they provide us with things that we desire, transport, heat, light and so on. The fault, as it were, is not in our suppliers but in ourselves.

Of course, as many do around here, it's entirely possible to reject the entire thesis. But working within the logical structure of the IPCC we still end up with the result that a tax which falls upon consumers is the correct action: as every single economic report about the problem, from Stern through Nordhaus and the IPCC itself, has pointed out. Because it's the consumers who are the polluters and yes, the polluters should pay.