This grammar school ding dong is so confusing

To us the arguments of grammar schools are almost exotically simple. The customers of the school system are the parents of the children in it. Systems should deliver what customers want. Thus those parents who wish to have a selective school system should be able to have one.

We would also note that those who wish to have a non-selective school system are equally free to send their children to one. We know of no one who does advocate grammars who insists they must be universal. That insistence upon uniformity only works the other way, those insisting upon a purely comprehensive system. And that too makes the decision of which side to support exotically simple. One side is stating that they want this and you can have what you want, the other insisting that everyone must only have the one system, choice must be denied.

Grammars it is then.

But even within the arguments being offered there is confusion:

Theresa May’s personal crusade to expand the number of grammar schools is in serious jeopardy today as senior Tory, Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs unite in an unprecedented cross-party campaign to kill off the prime minister’s flagship education reform.

In a highly unusual move, the Tory former education secretary Nicky Morganjoins forces with her previous Labour shadow Lucy Powell and the Liberal Democrat former deputy prime minister Nick Clegg to condemn the plans as damaging to social mobility, ideologically driven and divisive.

The opposition is clearly nothing but ideologically driven but that's just the normal hypocrisy of politics. But this insistence upon social mobility is a mark of the confusion among those arguing.

Social mobility, near always and everywhere, has been low. The UK's measure of it isn't very different from other countries, other places with very different school systems - say Sweden, as Greg Clark's research has shown. The one great burst of social mobility was post-WWII, but that's not quite what it seems either. We tend to apply greater social status to indoor work, no heavy lifting, and those decades were when the economy shifted from mass manufacturing into those sorts of services. And this happened right across the Western world and there's just about no correlation at all with the underlying school system.

But what really flabbers our ghast is that people are talking about social mobility when what they mean is economic mobility. For that's how they measure it, income of children relative to income of parents. And it's absurd to have a conversation in England, of all places, which confuses the two issues. Social position, in this of all countries, is more about whether you use a knife to eat your peas rather than how much money you make. Polly Toynbee may have emulated* Barbara Ehrenreich's Nickled and Dimed by trying out a few week's of society's scut work but she was still the gg granddaughter of an Earl and that matters in England.

We find this whole discussion, as at the top, very simple, exotically so. What confuses us is why everyone else seems to get so confused.

*That's one, rather polite, description of the genesis of "Hard Work"

We do have to say this, Duncan Weldon is entirely correct here

Up to a Copperian Point Weldon is correct that is. It is entirely true that if the British State is to carry on spending in the manner of that nautical shore leave then taxes must rise to match:

Back in the 1960s and 1970s tax receipts averaged around 38% of national income, but after a large drop in the 1980s they have bounced around the 34% to 36% mark ever since.

...

Despite all the rhetoric on the pressing need for deficit reduction, since 2010 the burden has fallen mainly on the spending side of the ledger. Current tax receipts stood at 36.4% of the economy in 2010-11 and by 2015-16 had fallen to 36.2%. Meanwhile, government spending as a proportion of the economy was cut from 44.9% to 40%.

Quite so. And there is a political choice to be made here. We can have the low tax low redistribution near laissez faire of Hong Kong, we can have the high tax and redistribution heavy social democracy of the Nordics and we can also have this middle way, the Anglo-Saxon muddle through the middle which characterises the US and UK. It's pretty clear which of those we ourselves would prefer but it is also equally obvious that this is a choice, it's a vision of the good society and it's perfectly valid to aim for any of the three.

But here's the thing. This is Britain and thus which of the three we aim for will depend upon the wishes and desires of Britons en masse. And we can very easily get the inhabitants of these sceptre'd isles to tell us that they'd just love more government services and more hand outs and that Nordic welfare state. But when push comes to shove we come up against revealed, rather than expressed, preferences:

Not since 1992 has one of the major political parties felt able to commit itself openly at an election to raising one of the major taxes – the basic and higher rate of income tax, NICs or VAT.

..

In the past few decades only Gordon Brown’s increase in NICs in the early 2000s – a pledge explicitly linked to the NHS – has received broad public support.

We Brits will happily contemplate getting more from government but we're not willing to pay government to have them. That is, we're not being serious, we don't in fact want these things at all.

To have that Nordic state would mean paying (much) more in tax. We won't pay much more in tax - thus we're not only not going to have the Nordic state we don't want it either.

Ho hum, looks as if we're stuck with that Anglo Saxon through the middle thing then, much as we ourselves would prefer the Hong Kong option.

We know Polly Toynbee doesn't like Murdoch but still

Even though we all know that Polly Toynbee really doesn't like Rupert Murdoch we do think that rather more evidence than this must be used to decide upon whether he may buy those parts of Sky that he doesn't already own. For Polly's tirade really just isn't enough:

She had no real choice. The culture secretary, Karen Bradley, this morning referred to Ofcom the Murdochs’ 21st Century Fox bid to take over all of Sky. Ownership of the remaining 61% would bring them enormous future profits and greatly expand, yet again, their control over British media.

Way to go Polly, way to go. In order to gain access to those enormous future profits it is necessary for them to purchase the parts of the share register which they do not currently own. The market value of those parts being the net present value of that future profit stream of course.

After 10 years, the deal last time said, Sky News would revert to Sky control. In those 10 years we can expect to see a groundswell of pressure to change the laws that impose strict impartiality on British broadcasting. Hear the drumbeat already. How stiff and staid is our TV news! How old-fashioned, in the new media circus of raucous opinion! Fox News makes a fortune, unlike Sky, which loses heavily, so take off the gag, let news be noisy and exciting!

If people wish to have a biased news source then why should they not have access to a biased news source? We here might complain about the Guardian's slant on matters but we most certainly don't think that government should insist it start telling the truth occasionally. And no, we cannot see the difference between pixels that appear, static, upon your screen and pixels that move around upon it.

We might also make a comment or two about how the BBC's influence is rather an elephant in the room when discussing media plurality in the British marketplace and so on. But let's cut right to the important point here.

Those shareholdings in Sky which Murdoch wishes to buy are currently the private property of those who own them. Polly's demand is that they should not be able to dispose of their own private property, as they wish - for don't forget that an offer must be made which tempts them to sell - simply because Ms. Toynbee doesn't like Rupert.

It's true, there are times when we don't allow people to sell their own as they wish. We're just fine with restrictions upon trading with the enemy in wartime for example. But however much La Toynbee is the grande dame of British journalism we're not convinced that such breaches of property rights are justified just because she thinks she has enemies.

How to get high-er revenue

In common with Milton Friedman, the ASI is skeptical about most taxes, especially proposed new ones. There is, however, one new tax the government might consider to plug the holes in its finances. It is a recreational narcotics tax.

It would involve first passing a law to remove their illegal status, but it would yield immense advantages. In the first instance it would undoubtedly raise billions of pounds in revenue. Last year the direct taxes on tobacco products, excise duty plus VAT, raised £12bn. This does not include the income tax paid by the industry's employees or the tax on the profits made by their sale. Undoubtedly a recreational narcotics tax would make a major contribution to the Treasury's coffers.

It would also enable quality controls to be put in place to greatly reduce the incidence of contaminated doses or overdoses. Labelling would protect users. It would cut crime massively, with some users no longer needing to engage in criminal activity to fund their use. Without their criminal status, there would be no turf wars between drug gangs, or the shootings and stabbings that characterize them. Government would save money on prisons, hospitals, and policing.

Even with the tax, legal narcotics would be cheaper than ones which today carry the costs of criminality. The many current users in conflict today with the police and the courts would be brought within the law and have no such cause for hostility.

The main losers would be the dealers and the criminal gangs which are part of today's supply chain. Examples from overseas show the positive results of such measures. By adopting such a tax, government could reduce the pressure on other taxpayers without incurring the wrath of those newly taxed, a group that would overwhelmingly back the measure. It might be time for it.

What we really don't like about corporation tax

Most readers of this blog will be aware that we don't much like corporation tax. In various blogs, articles and reports we've called for its abolition and replacement. We've argued that it falls heavily on workers, discourages investment and encourages excessive accumulations of debt.

But I think it's worth getting into the fundamentals of why we think corporation tax is so harmful and what you'd need to do to fix that.

Simply put, corporation tax taxes capital (goods that produce other goods, from new machinery to training and professional development) and taxing capital deters firms from investing in their workforce, lowering productivity and wages.

People invest money today in order to spend it at a later date. By taxing investment you essentially are imposing an uneven tax on consumption. You're taxing people who invest and wait to spend their money at a higher rate than people who spend it immediately. And it gets worse: the longer you wait to spend your money the higher the consumption tax rate will be when you do. In fact, relatively low tax rates on investment can imply extremely high rates on consumption down the line. I wrote a blog a few months back explaining the maths behind that.

But while there's a lot wrong with corporation tax, fixing it is actually quite simple. Let's think about this from the point of view of a business. Pretend you own a widget factory and you're deciding on whether or not to invest in a new Widgetmatic 3000 widget-making machine. You'll only make a marginal investment if the return you get from it outweighs the cost of investing.

There's a lot for you to consider. First, you need to know how much the actual machine costs to buy, then you need to know at what rate it will depreciate at and what the interest rate is. You also need to know what tax rate you'll face on the investment. If the return from the investment will be taxed that will increase the cost as well. For instance, if the rate of corporation tax is 20% and you can't deduct the cost of the investment at all from your taxable income then that adds 25% onto your cost of capital. (Think of it like a sales tax: 20% off a £125 jacket raises £25 leaving the retailer with £100. In essence, the sales tax has increased the price from £100 to £125, a 25% increase.)

But suppose you could deduct half the value of the investment from your taxable income. That'd lower the cost of capital to 12.5%. The bigger the deduction, the smaller the effect the headline tax rate has on the cost of capital. If it's a full deduction, then the tax rate is irrelevant. If you want a more mathematical proof, check out Alan Cole's Tax Foundation report on it.

As it stands businesses can gradually deduct the cost of an investment from their tax bill over the years as it depreciates. But unlike normal business costs like purchasing pens and papers, the purchase of a new widget-machine wouldn't necessarily be deducted in full the year it was bought.

Herein lies the problem – things are worth more now than they are tomorrow. It's simply better to have £50 today than £10 every year for five years. That's because you can put that £50 in the bank and collect interest. You've also got to deal with the value of that £50 being eroded by inflation.

If you let people deduct the full cost of an investment just like any other business cost, then the tax rate doesn't matter. Corporation tax would become what we call a cash-flow tax, a much simpler way of raising revenue. It would effectively tax consumption and profits above the normal rate of return (what economists call rents).

Instead of complicated corporation rates where businesses have to hire accountants to manage a range of investment allowances and depreciation schedules, a business would only be taxed on its annual turnover minus its investments and normal business costs.

Moving to such a system would be rocket-fuel for investment, boosting GDP and wages. When Estonia replaced their corporate income tax with a cash-flow tax levied on shareholders they attracted significantly more investment than neighbouring countries. This is the idea at the heart of a lot of free-market plans to abolish corporation tax, with both the IEA's Diego Zualaga's and the TPA's Single Income Tax plans featuring Estonian-style dividend taxes.

Many economists have argued the theoretical case for increasing and speeding up depreciation deductions, but it's been hard to prove empirically because we can't usually isolate the effect on investment from other bigger macroeconomic changes. However, a new paper from the Oxford Centre for Business Taxation backs up the intuition that it's the deductibility of an investment that really matters with proper empirical evidence.

On the EU's recommendation in 2004, the Labour government changed the definition of SME, allowing many more companies to qualify for First Year Allowances (FYAs). FYAs let you immediately deduct the full cost of an investment up to a certain amount (rather than deducting it as it depreciates). Devereux and colleagues compared those firms that now qualified for these deductions with firms that never qualified throughout the process. They found that investment rates increased 11% relative to firms that didn't qualify.

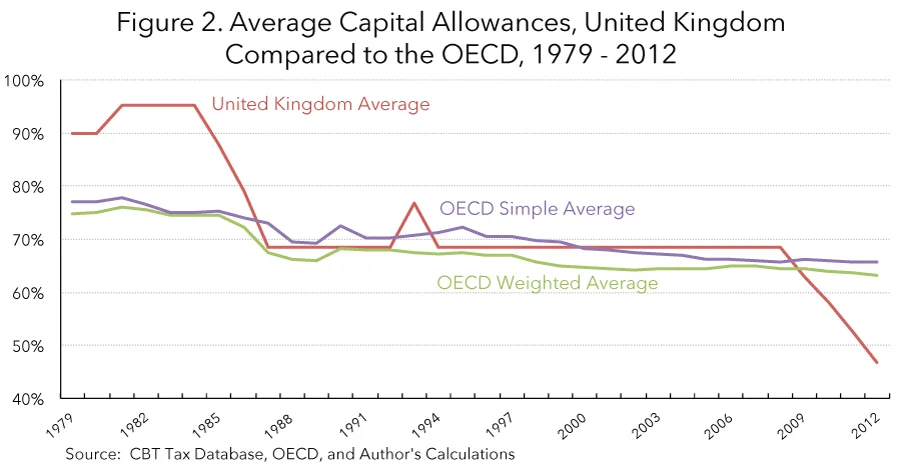

Over the past few years, the government has been focused on lowering the corporate tax rate. This is broadly speaking a good thing: the corporation tax as it stands deters investment and a lower rate will deter it less. But as The Tax Foundation's Kyle Pomerleau points out there's been a big problem. As they've cut the headline rate, they've also lengthened depreciation schedules. Think back to the widget example, they may have the main rate but they've also cut the deduction to make up the revenue.

That's a problem. Pomerleau points out that even though the corporate income tax rate has declined in the United Kingdom, the effective marginal tax rate on corporate investment has actually increased. We actually have a higher effective marginal tax rate on corporate investment than the US (the third highest in the OECD). In tax terms, the cost of buying a new Widgetmatic 3000 is higher now.

That explains why despite having one of the lowest corporate tax rates in the OECD, Britain persistently invests significantly less than the OECD average. It might even go some of the way to explaining why Britain's consistently lags behind our friends in Europe and America.

Devereux's findings shed light on the solution. Let's switch to a cash-flow tax to boost investment and give British workers a well-needed pay-rise.

A little something about those child poverty figures

When some statistic that we're all supposed to be shocked and disgusted by is trundled out it's always worth pondering upon what the statistic actually is:

The upward trend in child poverty in the UK has continued for the third year running, with the percentage of children classed as poor at its highest level since the start of the decade, latest official figures show.

Child poverty is an emotional term but it does not mean waifs about to be stuffed up chimneys in order to earn their daily crust:

About 100,000 children fell into relative poverty in 2015-16, a year on year increase of one percentage point, according to household data published by the government on Thursday. About 4 million, or around 30%, are now classed as poor.

This is relative poverty. Children living where household income is below 60% of the median, adjusted for household size - and usually measured after housing costs. This is not a measure of poverty of course, it is a measure of inequality. And as such there's a point or two that can be made about it:

The Institute for Fiscal Studies said income for working-age adults was no higher than eight years ago. Inequality and poverty remain slightly lower than before the financial crisis.

Recessions cut inequality and therefore, bizarrely, cut poverty by this measure. It is profits and capital incomes which fall fastest and furthest in a recession, meaning that it is the richer, where such are concentrated, who lose most. This compresses inequality. And as the recession recedes then it is capital incomes which grow again, increasing inequality.

We're thus using a very odd measure of poverty here, one which shrinks as we all get poorer (a recession does do that) and grows as we all get richer (a boom does do that).

However, we can go further than that too:

The data showed that nearly half of single-parent children are poor, with a noticeable surge in poverty over the past year among children of lone parents who work full-time.

Note again what our measure is here, it's household income. One which we might think is going to be lower where there's only one potentially working adult rather than two. And 25% of households containing children are headed by a single adult, 75% by a married or cohabiting couple. Their working arrangements being:

In spring 2004 most working-age families with dependent children (couples and lone parent families combined) had at least one resident parent in employment (84 per cent) and a half had two parents in employment (50 per cent).

The median income is, as we know, where 50% of households, assuming we are measuring median household income of course, where 50% of the units are below, 50% above. 50% of UK households with children in have two adults working, 50% have only one or perhaps none.

It is not hugely surprising that a majority of the children in families with only one potential bread earner are in households with income significantly below the median given that modal set up of the two earner family.

At which point what is our child poverty statistic really telling us? Britain has a certain amount of inequality, a little less than it had 8 years ago but rising again as we climb out of the effects of the recession. This may or may not worry you. It does not particularly worry us.

Britain's child poverty is also, in large part, caused by measuring it against median household income, something which is naturally going to be lower in single parent households where the norm is two earner households. This also does not worry us very much on the grounds that if people prefer to live their lives this way then who are we to gainsay them? This is not widows struggling to bring up their semi-orphaned children after all.

It also poses something of a policy problem - if it is single parenthood where this dreadful child poverty, that inequality, problem is concentrated then what actions should be taken about it? Anyone up for returning to the social pressures of old where the insistence was upon two adults raising children?

No, us neither even though that would seem to be a solution which would largely solve the problem being complained about. Ourselves we say leave people to make those decisions as they will for we are in fact liberals. We just have to put up with the resultant inequality of incomes in households containing children.

What we can't see as being quite just is to tax those doubling up that child raising duty in order to provide for those who eschewed that choice. To tax to relieve actual poverty, deprivation, yes, we can see that, but not inequality brought about by choice.

What Brexit means for Ireland

As the ASI’s resident Irishman, I was asked to speak at an event at the Irish Embassy yesterday to consider, among other things, what sort of impact Brexit will have on Ireland and the Irish people. Although Ireland is small, its destiny matters to Britain. Ireland is the United Kingdom’s only land neighbour, Northern Ireland is still unstable, 5.1% of British exports go to Ireland (nearly as many as the 5.7% that go to France), half a million people born in the Republic of Ireland live in the UK, and six million Brits have at least one Irish grandparent.

As the ASI’s resident Irishman, I was asked to speak at an event at the Irish Embassy yesterday to consider, among other things, what sort of impact Brexit will have on Ireland and the Irish people. Although Ireland is small, its destiny matters to Britain. Ireland is the United Kingdom’s only land neighbour, Northern Ireland is still unstable, 5.1% of British exports go to Ireland (nearly as many as the 5.7% that go to France), half a million people born in the Republic of Ireland live in the UK, and six million Brits have at least one Irish grandparent.

Irish people living in the UK don’t have much to worry about from Brexit, beyond the normal concerns Brits have too. The right of Irish people to reside in the UK does not come from EU law, but rather stems from British domestic law. The Common Travel Area (CTA) between Ireland and the UK predates our countries’ EU/EEC membership and, provided Ireland does not join the Schengen agreement to get passport-free travel with the rest of the EU, there is little reason to think that this will change. This bilateral deal means that Irish people in the UK are already protected under UK law, unlike EU citizens (whose status should also be guaranteed immediately and unilaterally by the British government, and who remain in limbo until it is).

The CTA is totemic when it comes to Northern Ireland, because it allows easy travel across the border, and any attempt to undo it would create serious problems there – avoiding even the perception of any backsliding on the progress made in Northern Ireland is a very high priority for everyone involved in the Brexit negotiations.

I think the difficulty of the UK ending freedom of movement while maintaining the Common Travel Area has been overstated somewhat. Freedom of movement is better understood as freedom to work and reside, which is normally not enforced at the border with people from countries we allow visa-free access to. For example, a Canadian citizen travelling to the UK can assume they will be granted access at the border to the UK without getting a visa first, but cannot stay here for more than six months or work here without getting a visa. Assuming we impose some controls on immigration from the EU27, but keep allowing visa-free travel, we will not be blocking Poles or Spaniards at the border but will be preventing them from getting a job (by punishing employers who hire them and deporting people who stay for longer than six months).

The challenge will be to actually keep track of when EU citizens have entered the UK, so that that six month period is actually enforceable. In my view the best solution to this is to carry out checks on travellers between the island of Ireland (that is, both the Republic and the North) and the UK, and to have a more relaxed policy about people travelling from the Republic to the North. A unified border system along the lines I laid out in “The Border After Brexit” would make enforcement of immigration controls much easier, allowing British and Irish border forces to track entrants more easily.

Customs checks are a bigger problem, and may prove to be quite costly for the Irish and British economies. Even with a very comprehensive free trade deal, it is likely that UK exports will be subject to ‘rules of origin’ checks by the EU. These checks are designed to prevent people by-passing tariffs by moving goods through middleman countries with low or no tariffs between both the origin and destination countries.

Imagine if the EU had 20% tariffs on Japanese goods but the UK had none on them, and the EU and UK had no tariffs between them. UK firms could import goods from Japan at zero tariffs and then sell them to the EU, again at zero tariffs, by-passing the EU’s tariff barriers. Rules of origin checks are designed to prevent this, and they mean that customs checks will still have to take place.

These can slow down the movement of goods and these delays can be unpredictable. For some products this can increase costs exponentially – for example food and pharmaceuticals that need refrigeration, which may spoil if they are unexpectedly delayed. I suspect these are unavoidable now that the UK is leaving the EU’s Customs Union, and will probably raise costs for Irish importers and, assuming the UK introduces similar checks, for Irish exporters.

Norway (which is outside the Customs Union and so subject to these Rules of Origin checks) and Sweden have minimised the burden of these checks at the border by creating a law enforcement and customs check zone 15km on either side of the border where police and customs officials from both countries can operate on both sides. Automatic number plate recognition allows for easier tracking of vehicles and unified customs paperwork reduces time, costs and complexity. In principle there is no reason that this should not be replicable between Ireland and the UK.

Of course tariffs and regulatory trade barriers on either side between the EU and UK will hurt both sides. I am optimistic about the prospect of a zero-tariff deal but not about the prospect of regulatory trade barriers being kept to a minimum, given the complexity of the issue, the lack of goodwill on both sides of the negotiating table, and the fact that many Conservatives do not seem to believe that regulations as well as tariffs can be a barrier to trade.

We should be careful not to overestimate the effects on the Irish economy of barriers to trade with the UK, however. 14% of Irish exports go to the UK – a hefty proportion, but less than the 20% that goes to the US and roughly 50% that goes to the rest of the EU. The UK is now a much less dominant trade partner for Ireland than during most of the twentieth century when as late as the 1970s more Irish exports went to the UK than all other destinations put together (in the late 1940s and early 1950s, 90% of Irish exports went to the UK!). Incidentally, this is one reason that Brexit is unlikely to provoke an “Irexit” – the UK just isn’t as important a trading partner as it once was.

Apart from these direct effects, if Brexit reduces UK growth it will probably hurt Ireland too. You might say that when the UK catches a cold, Ireland sneezes – a 1 percentage point drop in UK growth seems to cause a 0.3 percentage point drop in Irish growth. One study projects that Irish GDP will be 0.8-2.7% lower by 2030 (almost as low as the UK) because of Brexit, but there's a lot such things cannot capture.

Dublin may be able to attract at least some City firms that need to move some operations into the EU for passporting purposes. Dublin is English-speaking and well-connected to the US, and Ireland is less taxed and less heavily regulated than France and Germany. But Dublin is also quite a small city, with a much smaller talent pool than London, and very high property prices caused by tight planning laws (though less high than London’s). It would only take a portion of the City moving to Ireland to substantially boost the Irish economy, and if Ireland could make itself attractive to them as a base in the EU it could find that Brexit turns out to be a net positive. Over thirty large insurers are in talks with the Irish Central Bank to relocate to Dublin.

The most serious long-term problem for Ireland after Brexit may be political. The UK and Ireland have long been close allies within the EU, sharing a basic belief in (relatively) low regulation and low tax compared as the way to prosperity. With the UK gone, one of the most powerful voices for this “Anglo-Saxon” model and certainly Ireland’s most close and powerful ally will be gone. Ireland, as a country of four and a half million people, will not have much influence on its own.

The effects of this might be seen in a renewed push by the European Commission for a “Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base” (CCCTB) – a unified set of rules about what company money actually counts as taxable profits in EU states. The Apple case last year, in which the EC tried to force the Irish government to collect tax from Apple to stop it from acting as a sort of tax haven, was part of this area, and if a CCCTB is passed then harmonisation of the corporation tax rate may be next on the agenda – something that would be very bad for Ireland, which has attracted a lot of investment thanks to its low 12.5% corporate tax rate. Thankfully for Ireland, this is quite unlikely given the fact that matters of taxation at EU level require unanimous consent, giving Ireland a veto. Ireland is therefore only at risk if it decides to succumb to political pressure.

The optimistic thing about Brexit is that it might end up disrupting a lot of the sclerosis in Britain’s politics, giving us an opportunity to reexamine things like our own tax and planning systems – for instance, replacing corporation tax with a border-adjusted cash flow tax like the one being proposed by the Republicans in the US, which would shift the burden of tax from capital to consumption and boost investment and growth as a result. That would be very good for Britain and maybe for Ireland too, as growth here would drive growth there as well, though Ireland would lose much of its attractiveness as an international investment destination – its neighbour would now have a 0% corporation tax! A shift by Ireland to this kind of tax would of course give it that nice little advantage instead.

Brexit isn’t coming at the best time for anyone (both the British and Irish governments would like to have more wiggle room in terms of spending than the austerity-strapped budgets they have) but it’s happening and Ireland will have to ride out the storm. The UK matters less to Ireland than it once did, and unless Brexit is truly catastrophic for the British economy (my guess is that trade barriers with the EU will make us a bit poorer, but there are also big gains to be made if we take them) the main challenges are in implementing things like border and customs checks in a way that minimises time and costs, and figuring out how to stop the EU from turning into something very hostile to Irish interests.

Many Irish people are shocked that Brexit is happening, and fearful about the future, but if Ireland can tempt over some of the City's banks, it may find that England’s difficulty is its opportunity.

We thoroughly approve of this national insurance backtracking

This will be, is being in fact, painted as a disastrous u-turn, career ending damage, the beginning of an omnishambles, (cont. page 94.) and yet we here thoroughly approve of the reverse that has happened in this short period since the Budget over national insurance contributions for the self-employed.

Not because of any insistence we have over the policy itself nor of the personalities involved. The collective view veers one way and the other on those two but none of us think that they're hugely important. But reversing a mistake, now that is welcome.

For mistakes do always happen, there is never going to be a system containing human beings and human decisions that doesn't contain more than the occasional oopsie. As here:

Philip Hammond has abandoned plans to raise national insurance for self-employed workers in this Parliament after admitting that it breached the "spirit" of the manifesto.

The Chancellor provoked a furious reaction from Tory back-benchers after using his Budget to announce plans to raise NI contributions for the self-employed by 2 per cent.

Mr Hammond has written to Tory MPs saying that while the changes are justified the Government has chosen not to go forward with the rise in "class 4" national insurance contributions.

Oopsies will happen, just as most business ideas will fail, there's always going to be a business cycle, bad luck will dog some people and so on. What matters is what we do when that mistake is made, that bankruptcy is obvious, that recession arrives, that disaster is visited upon the unfortunate.

One reason we so like the market system is that the mistake of a bad business idea becomes rapidly obvious and people stop making that mistake. They run out of money and that's that. Politics tends not to work that way because all the playing is done with other peoples' money and as St. Maggie pointed out it takes a long time to run out of all of that. Until it does happen the practice is run upon reputation, careers, ego - and it's easy enough to spend an awful lot of other peoples' money on protecting those. Yet here we've had only a week to reverse what is said to be a mistake, something we find encouraging.

We're note really sure whether it was a mistake or not, whether the reversal is one or not. But normally political mistakes run on and are stoutly defended to the death of the last kulak. That politics might correct such errors rather earlier, more like a market system would, we think to be a Good Thing.

Transforming National Insurance

The now-withdrawn proposal to raise National Insurance rates for self-employed people from 9% to first 10% and then 11% has achieved one positive thing. It has drawn attention to the absurdity of the dual system of income tax and national insurance. Dan Hannan’s piece in the International Business Times makes the point that the retention of National Insurance is done to conceal how much tax people are paying. He says people would be very angry if they knew that in addition to their basic rate of income tax at 20%, their National Insurance payments took it to a very much higher level.

He is correct, but an honest government should let people know what tax they are paying, even if it changes their readiness to submit to tax increases. The two taxes on income should be merged. In the first instance the myth of insurance should be exposed by renaming it a National Insurance Tax, and having it at the same rates and thresholds as income tax. Income Tax plus National Insurance Tax would together constitute a “Personal Tax’ that people paid on all earnings above the starting threshold. A basic Income Tax of 20% plus the 12% employee contribution to National Insurance Tax would give a Personal Tax of 32%.

Government could thus merge the two without having the headline basic rate of Income tax leap through the roof. It would, however, make clear to people what they were actually paying in Personal Tax, and would end the anomalies of having different thresholds and separate calculations.

There is more, though. In addition to the employee contribution to NI, there is the so-called employer contribution of 13.8%, so-called because in reality it comes from the wages pool paid by the employer and would otherwise be available as wages. Although it is called an employer contribution, in fact its incidence falls on the employee. This could initially be renamed the employer contribution to National Insurance Tax. Personal Tax would then consist of 32% paid by the employee, and 13.8% paid by the employer, for a total of 45.8%.

Once this change had bedded in and yielded savings in simplification, the employer contribution to National Insurance Tax might be given its real name, “Employment Tax.” It would be seen for what it is: a disincentive to create employment. It might also add to popular pressure for further simplification of the tax code and to heightened intolerance of government wastage.

The FT's odd suggestion about the EIB

As we all know the government is considering asking for the capital back from the European Investment Bank when Brexit occurs. There's perhaps € 10 billion in there and according to the rules shareholders in the EIB must be EU members. All of which seems pretty cut and dried to us.

Which brings us to this remarkable suggestion in the FT

:But the obvious point here is that a proportional slice of the EIB’s funds is far smaller than the cash the UK would receive over the years by remaining a member. A one off payment in return for losing billions of yearly funding.

Err, what?

I shouldn't sell my stock in Barclay's because of the loans I can get from Barclay's? Loans which I do have to pay back note, so the loans aren't free money. While that return of capital is in fact free money, money that we're free to deploy in any manner we desire.

More than this it's not exactly as if the UK has a problem in borrowing money these days, is it? The Treasury can in fact borrow near unlimited amounts at present, almost certainly at lower interest rates than the EIB would offer too.

Whether or not Britain should stay in the EIB isn't something we have a collective view upon. But the argument that we should stay in just because they might lend us some money is ludicrous.