To the late, great, Bob Bee

Robert Bee, 1925-2017

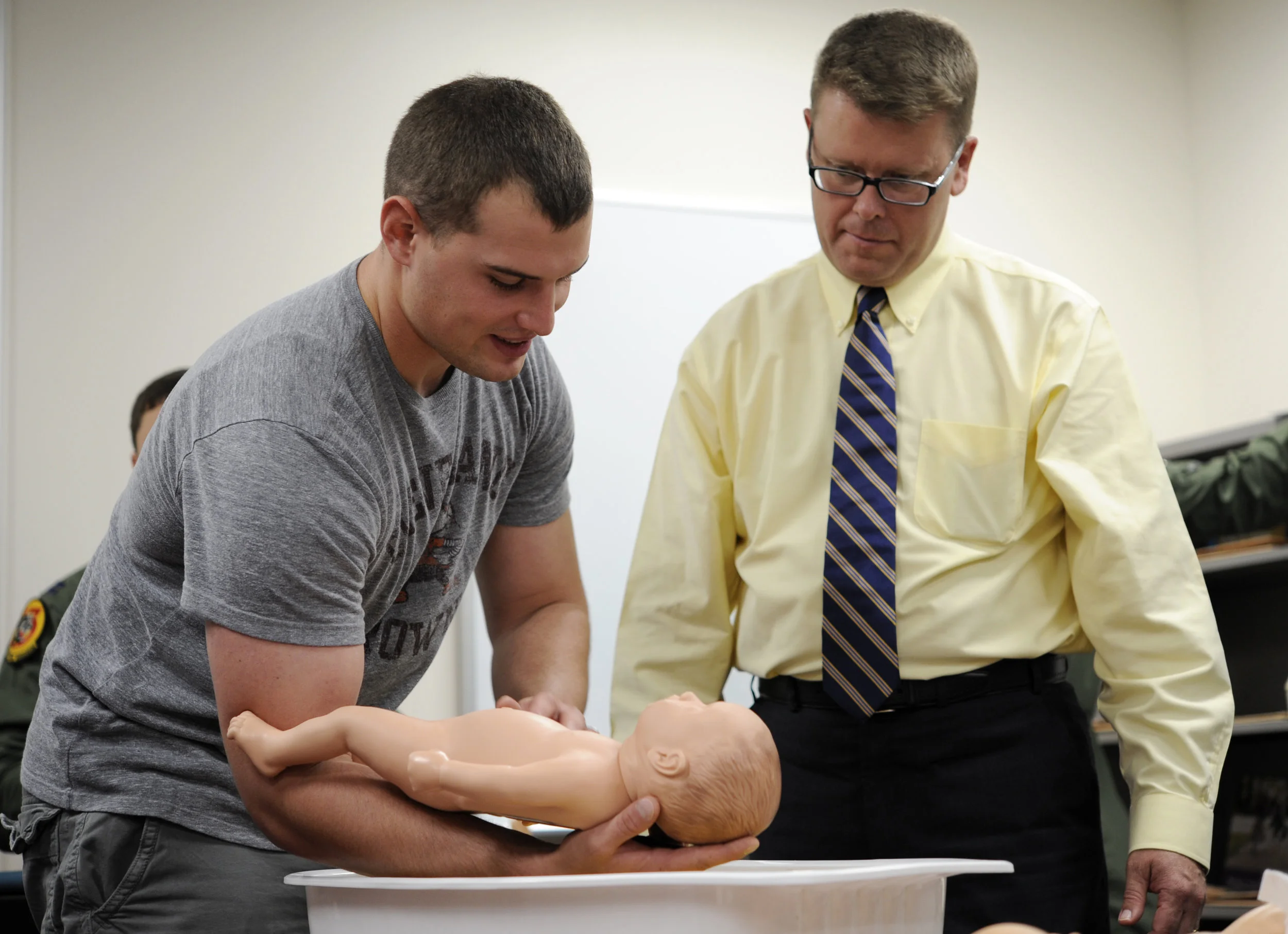

We were sad to hear of the death of Bob Bee, 92, former Chairman of the Adam

Smith Institute. He was a US citizen, but moved to London in 1978 to become

chairman of the London Interstate Bank. As a fervent supporter of liberty and free

markets, he joined the board of the Adam Smith Institute and soon became its

Chairman. He used his extensive City contacts to bring the ASI to the attention of

big names in business and industry, and encouraged them to participate in our

activities.

It was under his chairmanship that the ASI rose to prominence as a leading

exponent of the market oriented policies that ultimately unpicked the Keynesian

postwar consensus and lifted Britain out of the nightmare of rent controls and

nationalized industries.

Like others in the ASI, he had a mischievous sense of humour and was an

unfailing optimist and enthusiast, seeing problems as opportunities. It was only

gradually that we came to know that he had fought as a teenage GI in the Battle

of the Bulge, winning a bronze star.

His previous career had included a stint in the foreign service of the US Treasury,

and in Wells Fargo's International Division. Bob’s work in international finance

included posts in Ankara, Turkey, Bonn, Germany, and Karachi, Pakistan, where

he was Acting Director of the US Agency for International Development's

mission.

He took part enthusiastically in ASI activities, befriending its young staff. One of

their annual highlights was the dinner at his house, at which many different ice-

creams and sauces were served from a giant silver Indian dispenser originally

used for serving different spices. He accompanied ASI personnel to Downing

Street on several occasions as guests of the Prime Minister.

After he retired with wife, Dolores, to San Francisco, he continued his

association, and looked forward on regular visits to London to meeting the ASI's

youngsters over lunch. He told us many times how privileged he felt that he had

been able to play a role in events that shaped history. We in turn were privileged

to have known him and to have benefitted from the massive help and support he

gave.

As we thought there would be, there's a problem with this shared parental leave

We should note that this idea of shared parental leave is something that stemmed from this very blog at least in its British incarnation - the incarnation of the policy, not the blog of course. We pointed out a number of years back, and have repeated ad nauseam, that we don't in fact have a gender pay gap. We've a pay gap caused by the gender bias in primary child carer within a family. This was picked up by varied LibDems and so we got shared parental leave.

If 50% of fathers become the primary child carer and only 50% of women do in their familial arrangements then that gender bias will disappear as will the gap. That is also pretty much he only way that the gap is going to disappear.

So, shared parental leave. Unfortunately, not many are taking it:

Launched in April 2015, the government scheme is supposed to help mothers go back to work and allow fathers to take a larger role in caring for their children by permitting parents to split almost a year of leave between them.

Yet the take-up has been pitiful. Just 1% of eligible parents took advantage of the scheme in the year to March, according to HM Revenue & Customs, and one of the biggest reasons so few are doing it is that it doesn’t make financial sense.

The reason it doesn't make financial sense is because there are two different sets of people paying maternity/parental leave.

There is the statutory amount, perhaps £140 a week, which is largely (some 90%) paid out of national insurance receipts - by the reduction in taxes paid by the employer. Then there is enhanced pay which is as with a normal wage cost to said employer. It's them paying some amount to retain the services of the employee and is just a regular cost to them of doing business, paying the workforce.

That enhanced pay is generally only on offer to women, men generally only being offered the statutory amount. Economic logic thus leads to many fewer men taking up the offer. Although, of course, we can be curmudgeonly about this and point out that if men don't value a cut in pay for months of their new child's life then they don't value being there for those months all that much.

The demand is now becoming that men should be offered that same enhanced pay as women. But that then runs into a horrible problem - for the enhanced pay is a cost the employer, not us all through the tax system, has to bear. We can, entirely righteously, all vote on how our tax money is spent, we cannot righteously insist upon how others spend their own money.

At which point all is best left to the market itself. Just as with that enhanced pay to women of course. Employers pay it because they think it worth it to retain their employees. As and when enough fathers are interested in the same then they will no doubt be offered it - for exactly that same reason that women are. Because it benefits employers to do so.

This is, after all, how we solved the problem before so why not sue that same solution again?

If payday loans were ripping people off then there'd be a better profit margin than this

For the provision of a good or a service to be ripping people off it is necessary for someone to be making more than a normal profit or income out of that provision. If everyone doing the providing is, instead, just making the normal sort of money then it tells us that this good or service, whatever its price, is just expensive to produce or provide.

At which point some interesting numbers from the payday loan industry. Agreed, these are for the US but still, they're a useful insight:

A federal agency on Thursday imposed tough new restrictions on so-called payday lending, dealing a potentially crushing blow to an industry that churns out billions of dollars a year in high-interest loans to working-class and poor Americans.

The rules announced by the agency, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, are likely to sharply curtail the use of payday loans, which critics say prey on the vulnerable through their huge fees.

Currently, a cash-strapped customer might borrow $400 from a payday lender. The loan would be due two weeks later — plus $60 in interest and fees. That is the equivalent of an annual interest rate of more than 300 percent, far higher than what banks and credit cards charge for loans.

OK, agreed, this is expensive. But in order for this to be preying there does have to be some evidence of outsized returns.

The operators of those stores make around $46 billion a year in loans, collecting $7 billion in fees.

OK, fees include the costs of running the stores, paying the staff - and no, we don't think that's a highly paid job - covering the defaults and so on.

The restrictions, which have been under development for five years, are fiercely opposed by those in the industry, who say the measures will force many of the nation’s nearly 18,000 payday loan stores out of business.

There are many such stores, we'd expect competition to rather lower the profits of the industry.

A dropoff of that magnitude would push many small lending operations out of business, lenders have said. The $37,000 annual profit generated by the average storefront lender would become a $28,000 loss, according to an economic study paid for by an industry trade association.

We've 18,000 stores each making an average of $37,000, that's total profits of $660 million, a lovely number for something considered so perfidious. There're $46 billion of such loans a year, making the profits 1.43 % of the amount advanced. That's not in relation to capital employed of course but a 1.43 % reduction in interest charged - or fees - would seem to wipe out the industry as a profitable enterprise.

At which point we've our answer, which is that this isn't a rip off as there is no excess profit or income from the provision. It's just a very expensive service to provide.

As to what that means should be done, well. We think that consenting adults should indeed be able to live their lives as they wish. Others apparently don't. But there still isn't any justification about rip offs here to justify that second attitude.

In designing a welfare system - pay cash please

An interesting piece in The Guardian which underlines an important point about welfare systems - they should be paying out cash.

No one doubts that we're going to have some form of welfare system, the arguments are only about how much and how generous. But underlying the basic discussion we really do have to insist that however wide the system is it should be one which pays out real money which the recipients can then determine how to spend themselves:

We all have our own ways of dealing with the insecurity of poverty. For my father, food was a point of pride. No matter how close the wolf got to our door, we ate well. Food stamps helped, but my dad was also thrifty. To make up for splurging on pine nuts, we ate quick sale meat, government cheese, and tuna from dented cans. His resourcefulness paid off. We’d sit down together and eat chicken cacciatore and handmade pasta with garden salad with my mother’s special vinaigrette. He’d survey the table with an expression that seemed to say, “We may be poor, but we eat like kings.”

...

But the facade was deceptive. We weren’t the only family feeling the pinch. In the early 1990s, the Oregon logging industry was in freefall due to increased mechanization and changes in federal environmental policy. Logging jobs evaporated and the mills shut down one by one. When I looked at my classmates, I saw the facade: all-American kids in name-brand jeans and basketball shoes. It didn’t occur to me that other parents were scrimping and prioritizing, buying the kids Nikes and putting off paying the phone bill.

That choice was a matter of pride. Just as my dad attempted to protect us from food insecurity, my friends’ parents were protecting their kids from social scrutiny.

One part of this is that the poor value agency, just as the rest of us do. We are richer by being able to decide how our limited resources - and they are limited for all of us - are deployed to maximise our individual utility. And do not forget that utility is indeed individual.

This is not a universal - there are those we really do think are incompetent to make their own decisions and we also know that we're going to have to take many to most for them. But that's a very small part of any welfare state that is going to exist in any likely political reality. Outside that little arena whatever it is we do as either redistribution or simple social support should be provided in those interchangeable ration coupons called cash - even if these days that will be digital or in a bank account.

There's a flip side to this. US Census, which measures such things, readily agrees that the value to the recipients of Medicaid, food stamps, Section 8 vouchers and the rest is less than the cost of providing them. We could make all such recipients as well off as they are at lower cost, or make them better off at the same cost, by simply providing money rather than coupons, goods or services.

This should then inform our own design of whatever it is we're going to do therefore. Like, for example, housing benefit rather than council houses - in the absence of our actually solving the problem by liberating planning control of course.

For the truth is it is always more efficient to subsidise people rather than things, agency is indeed valuable and money allows the poor, like the rest of us, to maximise utility within our budget constraints.

It's the productivity, stupid

Here’s the real story of the week: productivity in Britain is only 1.4% higher now than it was ten years ago, so the public finances are even more of a mess than we thought. The lighter blue line in the chart below shows how we’ve done; the dotted yellow line shows the 1997-2007 trend.

Here’s the real story of the week: productivity in Britain is only 1.4% higher now than it was ten years ago, nineteen percentage points below trend, so the public finances are even more of a mess than we thought. The lighter blue line in the chart below shows how we’ve done; the dotted yellow line shows the 1997-2007 trend.

This is an astonishingly bad performance, worse than every other G7 country apart from Italy:

I believe that most of Britain's political problems are down to this. We’d be done with austerity if tax revenues hadn’t grown so much slower than we expected back in 2010. I don’t think you get Corbyn or the lurch against productive, tax-paying immigrants without years and years of near-zero wage growth for the median worker. And would Theresa Miliband really get away with proposing wage and price controls if the economy was chugging along normally?

No. Near-nonexistent productivity growth is the story of our age, and it’s a safe bet that it is why, when ten years ago we had Blair and Cameron, today we have May and Corbyn.

In describing this as the ‘productivity puzzle’, there’s an implication that this is all out of our control and that there’s nothing we could have done to avoid this. So instead we get the politics of managed decline – nationalising the railways so that we can subsidise them more, putting price caps onto energy companies so that their 3% profit margins can be eliminated, worrying endlessly about the salaries of the one hundred CEOs who run the country’s most successful businesses, holding the future of EU citizens hostage to extract concessions in a trade negotiation.

Managed decline is what the 1970s were about so it feels apt that Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn each represent a return to their parties’ 1970s policies. My strongest impression from this year’s Conservative Party Conference was of a party that is confused about what to do next and afraid about what happens if they get it wrong. And they should be.

Boris’s speech about “letting the British lion roar” lacked many actual ideas to boost productivity and wages – just attacks on Labour and repetition that the Tories were actually doing a bang-up job already. So who do you believe – Boris or your lying wallet?

In other words, the Conservative leadership seems out of ideas. But, at the Adam Smith Institute, we are not. When thinking about the work that the Adam Smith Institute has focused on in recent years, what struck me recently was how much of it is focused on solving this problem. Almost by accident, our focus on policies where small changes would yield big improvements to people’s lives has ended up with the core focuses of our work being on fixing the productivity ‘puzzle’. So, to whoever ends up running that Party once May goes, here’s your crib sheet for policy success:

1. Fix the housing market.

You saw that one coming, I know. There’s nothing we’ve talked about more in recent years than the housing market, which at its heart is broken because supply is so tightly constrained. It’s a mistake to think that this is best captured by looking at house prices, which are a function of interest rates as well as supply and demand. It’s much better captured by looking at measures of housing costs, like rents per square foot, which are mostly driven by simple supply and demand measures and are remarkably high by international standards.

This is not just a problem because it raises people’s cost of living. It affects productivity because high housing costs stop people from moving whether they can work most productively, and to such a high degree that the entirity of foregone productivity growth since 2007 might be achievable just by fixing the supply side. It also means that housing is most people’s biggest investment asset. That means that money that could have gone into productive business investment goes into the price of land instead. It also means that businesses can’t use property efficiently, because planning laws constrain land-use and stop, say, grocery stores from being easily turned into offices.

How to fix this? Our most recent report, YIMBY (Yes In My Back Yard!), has solutions to re-align incentives so that local landowners win when new developments take place near them. In the past we have suggested the use of planning permit auctions or changes to the rules around councils purchasing land that would allow them to capture the enormous uplift in value that takes place when planning permission is granted. And our famous report The Green Noose makes, to my mind, the definitive case against the green belt.

2. Rationalise the tax system.

Everyone knows that George Osborne cut corporation tax when he was Chancellor. And corporation tax receipts actually rose slightly after he did that – the Laffer curve in action, right?

Wrong. To offset the lost revenue, Osborne cut capital allowances, which allow firms to write off capital investments from their tax bill in the same way that they can write off wage costs and purchases of pens and paper. Even though the headline rate fell from 30 percent in 2007 to 20 percent in 2016, in practice this meant that for many firms the effective marginal rate did not fall by much, and for some it rose.

The more you invested in things like machinery and property as a business, the less you benefited from the Osborne corporation tax cuts:

The UK’s effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) on new investment actually climbed from around 20 percent in 2007 to 23 percent in 2010 even as the corporate rate declined by five percentage points. Overall, the EMTR only fell by three percentages points from 2007 and 2016, from 20 percent to 17 percent, while the statutory corporate tax fell by 10 percentage points.

This is obscure but incredibly important. Fix this, and go further by allowing firms to immediately write off the cost of their investments, and you will have effectively stopped corporation tax from falling on investment at all. Sam Dumitriu explains the logic behind this here.

Taxes affect behaviour in other ways too. In a forthcoming report, Ben Southwood will explain why stamp duty land tax is possibly the most damaging tax we have, gumming up the housing market and stopping people from moving to the house that suits them best – particularly elderly people who would like to downsize (freeing up their house for a younger family), but would face a massive tax bill if they did. Stamp duty brings in about ten billion pounds per year but probably costs us much, much more than that.

3. Get serious about innovation and immigration.

A Bank of England comparison of like-for-like firms operating in the UK found that foreign-owned firms were about 50% more productive than British-owned ones. The big reasons: foreign-owned firms invest in R&D more, are better managed, and collaborate with other organisations more.

Why? Andy Haldane has discussed this but his policy proposals are a little lacklustre, in my opinion, focusing on helping existing firms to raise their productivity. The work that’s being done by The Entrepreneurs Network, the ASI’s sister think tank, focuses on the other side of things – bad firms not being eliminated by betters rivals effectively enough.

It might be because our approach to regulation is excessively cautious, especially in areas dominated by the state such as healthcare. Mark Lutter’s paper from earlier this year outlined how we might make it much easier to use medicines and instruments approved for use abroad in the UK and encourage more innovation domestically. Regulatory ‘sandboxes’ and explicit rules that preserved permissionless innovation would help here too, but I don't think we have a full idea of how to solve this problem just yet, or indeed where innovation really comes from. Thanks to ASI stalwarts like Dr Anton Howes, we're beginning to understand the past, and on the policy side, watch this space.

It blows my mind when I hear politicians talk about making Britain a leader in innovation one minute, and then about the need to restrict immigration the next. Innovation is a product of institutions and people – so making it harder for would-be innovators to cluster in certain places to collaborate (and compete!) with each other probably doesn't help. Anecdotally, most of the tech startups and bigger tech firms I have spoken to in the past few years have said that cracking down on immigration has made life much harder for them, and hurt an area where the UK should be excelling.

There are two straightforward solutions to this. One, eliminate barriers to migration altogether between the UK and other countries above a certain income level – the rest of the OECD, say – and do not put new ones up. Two, allocate additional visas through a sale system where a would-be immigrant can pay a certain amount for the right to reside in the UK, instead of trying to micro-manage which industries have ‘skills shortages’. Get the best people in, and get as many of them as you can. We have a paper discussing this option in the pipeline.

Managed decline is a choice. On planning, tax, innovation and immigration the policies to reverse it are out there. We just need leaders who will take them.

Treth Twristiaeth? Dim diolch!

There has a been a lot of news recently so it might have passed you by but something genuinely staggering happened in this country last week. It wasn’t the Prime Minister bungling the most important speech of her life. Nor was it Theresa May getting confused between support for the free market and intervening in it. No, it was the Welsh Government’s budget – with the first taxes to be levied and collected by a separate authority in Wales in nearly 800 years.

Nationalists in Wales will be glad of this fact in and of itself. But should we be? Well powers for their own sake aren’t that interesting, it’s more about what’s done with them.

One of the things that came out of the budget wasn’t actually a plan to use them to create a power but a shortlist of potential new taxes. Mark Drayford, the economy minister of the Welsh Labour government in Wales, set out some possibilities. Among these were a new tourism tax and a new disposable plastics tax.

There is good reason to support disposable plastics taxes and Wales has a good track record on them. Wales was the first place in the UK to introduce a tax on carrier bags and the subsequent drop in use was a cornerstone of the argument in getting it adopted by other parts of the UK. Devolution as it should be – experimenting with good governance, working out what we want less of and using price incentives to change a negative outcome (after all there are some pretty nasty externalities that come out of plastic bags).

The problem is, that makes the second one on the list quite bizarre. Presumably the Welsh government thinks that tourists are a good thing for Wales, it certainly likes to appeal to them to come (and spend their money in local communities). But as we alluded to above we mostly use taxes, like plastic bag taxes, to get less of something.

Tourist taxes make sense where demand is inelastic – there’s only one Sagrada Familia and one Parthenon for tourists to visit after all. And taxing people that free-ride on public costs of keeping places like Venice afloat (literally), makes sense. But where demand is elastic, where it is responsive to price changes, then taxing tourists just makes the numbers coming fall and it reduces the economic benefits of tourism.

While the Tourism Alliance measures elasticity of the UK as a whole, it doesn’t give exact numbers for Wales. Yet there are some proxies that we can use that suggest the Welsh tourism sector is elastic and that this tourism tax would be a pretty poor idea.

The first is simply that the Welsh government advertises heavily both internally and externally - if you get high numbers of visitors turning up regardless of the money you spend telling people to then you wouldn’t bother (you’d hope).

The second is that the Welsh government themselves collect figures of visitors and their and Visit Britain’s own analysis shows swings with big increases in tourist numbers during the recession and dropping after as well as when the weather in the UK is poor (2012 was a particularly rainy summer in Wales and was just as the UK was recovering from the financial crisis).

Thirdly the falling value of the pound has had an enormous impact on numbers coming to Wales. In the past year tourism numbers are up 11%, following a drop in the pound after the Brexit vote.

The tourism sector supports 40,000 jobs in Wales, boosts GDP by £4.8bn per annum and the evidence suggests this (and the numbers of tourists coming in the first place) is price sensitive. If the Welsh Government wants to use a sector as a cash cow then tourism really isn’t the one to go for. Maybe it would be good for Wales to wait another 800 years before adding any additional taxes?

Strengthen neoliberalism & change the world

What sort of traits make someone amenable to neoliberalism? An inherent scepticism about the role of authority? A general optimism with a strong belief in one’s own self-worth?

It feels obvious that such traits are held by just a minority of people in society. Yet, one only needs to look at the scale of government reform that occurred across the developed world during the 1980s and ’90s to see something big was going on. Surely, the extent of policy changes far exceeded what was due to the minority amenable to neoliberalism. What caused this out-sized influence? And what does it suggest about how we can better spread neoliberal ideas?

A brief discussion of banking deregulation in the developed world suggests the sharing of credible policy experiences spreads neoliberal ideas. I support this by describing why I believe having societies share policy experiences acts like a filter, making neoliberal policies the ones more likely to be adopted. Organisations like the Adam Smith Institute devoted to spreading neoliberal ideas should encourage societies to share their experiences of different policies.

By the 1970s, the economic controls of banking put in place during and following the Great Depression were creating a raft of problems across the developed world. As a credible acknowledgement of these problems, some governments started instituting policy changes – it became more pressing for other governments to follow suit. For a 2011 MA thesis, I completed research studying banking regulation in seven developed countries: Australia, Canada, Germany, Norway, New Zealand, the UK and the US. Of these, all 7 significantly deregulated their banking industries between the mid-1970s and the 1990s.

It seems likely that the sharing of policy experiences, made more credible by accompanying policy changes, played a big part in why all 7 of my countries deregulated banking at roughly the same time. What’s to say though, that neoclassical policies will always be an outcome from such sharing? For example, the OECD Secretariat shares policy experiences between governments; neoliberal is not often used to describe the policies it recommends.

To be effective at promoting neoliberal policies, sharing needs to focus on the people in societies, and not on their governments. Defined broadly, it is societies that experience the full costs and benefits of different policies. Putting societies first acts like a filter generally removing more statist policies. Since intrusive government actions often have unintended consequences, it follows that reductions in the intrusiveness of actions will have fewer unintended consequences. This implies that societies will generally be more positive about and better at sharing policy changes that result in less intrusive government actions.

At the beginning of this post, I asked what factors might strengthen neoliberalism. A description of banking deregulation across the developed world suggests the sharing of credible policy experiences may achieve this. Having societies share policy experiences will act like a filter to ensure it is generally neoliberal policies that are spread. To strengthen neoliberalism, its proponents should encourage societies to share their credible experiences of different policies.

A bizarre argument about womens' empowerment

An interesting claim here, that we should indeed be concerned about womens' empowerment - something we agree upon at least - but that we must concentrate on their political empowerment, not the economic:

The assumption behind all of these donations is the same: Women’s empowerment is an economic issue, one that can be separated from politics. It follows, then, that it can be resolved by a benevolent Western donor who provides sewing machines or chickens, and thus delivers the women of India (or Kenya or Mozambique or wherever in what’s known as the “global south”) from their lives of disempowered want.

Well, yes, we tend to think that those who are dirt poor are not empowered in any meaningful manner. Further, that the very fact that one starts to create economic value empowers. Either through being able to command that economic value itself - we do all tend to agree that richer people have more life freedom - and also by being able to trade it. Other people would like to share in that value created, this gives you power over them.

In fact, a useful definition of either wealth or empowerment is the ability to command the labour and resources of others. Richer people, even if it's only be a couple of laying hens, have more of this.

But apparently we're wrong:

It’s time for a change to the “empowerment” conversation. Development organizations’ programs must be evaluated on the basis of whether they enable women to increase their potential for political mobilization, such that they can create sustainable gender equality.

Somehow we just can't agree with the idea that another march on the district office in favour of gender parity is going to be as successful as women owning economic assets, such in itself being most empowering. One of the joys of our argument is that Karl and Friedrich would agree with us. The relations of production really do mean that a change in the economic structure leads to a change in who has the power. That is, if, as they do now in the rich world, women have more economic power then they will also have both greater political power and greater gender parity.

Economic development thus bringing about the desired goal rather than being an alternative to it.

Force against Catalonia risks a high cost for Spain

It pays to stay ahead of the game. If you don’t plan or innovate as a business you find a competitor will appear in front of you. If you’re a political party that doesn’t catch voters' imagination you’ll find a rival beating you to office – the Tories might like to take note of this after a disastrous end to their party conference in Manchester this week. But what happens if you’re a country and you don’t move with the times to ensure you retain the support of your citizens?

In Spain this fortnight they’re finding out. It turns out that the cost of a rigid and unchanging constitution, that was designed to do one thing (namely, end a dictatorship and help the country transition to a modern democracy), is pretty high as it risks losing the respect of the citizens it supposedly serves.

Mariano Rajoy, the Spanish Prime Minister, has spent the past half-decade hiding behind the words of the constitution that demand the Kingdom be ‘indissoluble’. Yesterday the Spanish King himself appealed to these words to undermine the organisers of the democratic vote made on Sunday.

Catalonia’s independence referendum was a symptom of a system which doesn’t keep up with shifting priorities of its people. Catalans have, more and more, been drawn to a rival project that says it reflects better the aims, identity and aspirations of the people of Catalonia better than a government based in Madrid. These shifting priorities have come up against the hard fact of a constitution that Spanish authorities will not let bend.

Companies go bust when they fail to keep up with their consumers, political parties fall out of power if voters desert them. Countries are no different, if their institutions and structures don’t match their citizens’ preferences they find their authority dissipates totally and they unravel without extreme coercion. Beating old women, using military police to injure nearly a thousand of their own people, troops on the streets, and now suspending parliamentary operations makes it pretty clear that Spain is choosing the option of force. Spain should be more careful, its constitution and modern authority is derived from its commitment to democracy.

Flexibility, conciliation and a proposal to run a second and fully respected referendum could yet save Spain. It’s still an option for Rajoy and the Spanish establishment. It could win a vote if it gave its Catalan citizens the choice. It’s a risk that Spain should take. And, after a decade of intransigence and a weekend of violence it’s a right Catalonia has won. If Spain doesn’t take the risk, just like a business running out cash, the state will find (very quickly indeed) it doesn’t have enough Catalan supporters to justify its continued control of the region.

But what happens if Rajoy chooses to inflict pain on Catalonia? Frankly, Spain risks undermining not just its own authority but the legitimacy of the European continent to speak out on the issues of democracy and violence against citizens across the world – that’s one hell of a cost for the EU to bear in order to maintain the territorial integrity of a member state.

I have a small bet in the office. I am betting that the European Commission, its Parliament and its member states abandon Catalonia when it declares independence (which the Spanish court’s planned suspension of the Catalan parliament for next Monday has almost certainly made even more inevitable).

If I’m right, if Europe turns the other way and Spain is free to crack down on its own people without any international repercussions, it will show up the lie that the EU is a project that works for its citizens and not just its bureaucracies and elites. The European Union might just find its own authority goes as well and it risks a crisis of its own legitimacy – of those that were drawn to its nature as crossing boundaries and transcending national identities – the Catalan crisis is a European crisis too. Will the EU step ahead of the game?

If artificial meat does take over then climate change just isn't much of a problem

George Monbiot tells us all that artificial meat is soon going to be a real product rather than a lab curiosity and he could be right about that. However, it's what happens after that which interests here. George goes on to tell us that this will, quite obviously, curb all those emissions that raising livestock currently causes. And the subsequent rewilding of pasture will reduce emissions once again.

As the final argument crumbles, we are left facing an uncomfortable fact: animal farming looks as incompatible with a sustained future for humans and other species as mining coal.

That vast expanse of pastureland, from which we obtain so little at such great environmental cost, would be better used for rewilding: the mass restoration of nature. Not only would this help to reverse the catastrophic decline in habitats and the diversity and abundance of wildlife, but the returning forests, wetlands and savannahs are likely to absorb far more carbon than even the most sophisticated forms of grazing.

OK - don't think about whether this will happen but think about what if? The answer being that climate change stops being a problem.

If we take seriously the IPCC and the like reports then there are various scenarios for how emissions will turn out in the future. The whole problem being a serious one if we're on A1FI or RCP 8.5 (dependent upon which set of scenarios we want to use). It not being a serious one if we're on A1T or RCP 2.6. And the truth is that neither A1FI or RCP 8.5 are really even possible, let alone likely for we've already done more than enough to head them off. They both insist, for example, that the world will be using more coal in 2070 than it does now. Not just more but more as a portion of total energy provision. Given what has already been done with solar and wind power that's just not going to happen at all. And certainly not when we consider what is likely to happen to solar over the coming decades.

One of the sadnesses of the climate change "debate" is that whenever we see a new report stating that if we don't do something about climate change then - the results are always based upon the assumption that A1FI or RCP 8.5 are what is going to happen - entirely ignoring that we have already done something.

And this thought about artificial meat just adds to this. If it is true, that the technology becomes mainstream, then we are again moving further away from the predicted danger and much closer to the don't worry about it scenario.

At which point, of course, then we've got to struggle mightily a great deal less, don't we? That is, all these predictions of how things are changing just keep telling us how much less change needs to be done.

Oddly, very few people indeed tell us this.