It is often baffling how some Budget measures cause outrage while others pass by barely noticed. We all remember the furore about the tax credit cuts. But how many people remember that the same cuts will be applied to Universal Credit, which is replacing tax credits? This week’s cut to the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) is another example. Jeremy Corbyn denounced it as punishing “the most vulnerable and the poorest in our society”. The ink had barely dried before Tory backbenchers made clear their disagreements with the Chancellor. But of all the cuts that the Conservatives have made to disabled people, the cuts to PIP may well be the most sensible. They are almost certainly the least damaging.

The Adam Smith Institute's reaction to the 2016 Budget

Commenting on today's Budget, spokesmen for the Adam Smith Institute said:

Today’s budget was disappointing. Growth forecasts have been lowered, and the Chancellor’s failure to deliver any kind of growth agenda in the last Parliament has left the British economy vulnerable to a global economic slowdown. Even more worryingly, he doesn’t seem to care. There was nothing major in this budget to boost investment, and far from simplifying the tax system the Chancellor announced a raft of new levies that will make it even more complicated and wasteful.Mr Osborne seems so firmly focused on the politics of the budget that he seems to have ignored the economics of it altogether.

– Sam Bowman, Executive Director

Mr Osborne sounded a lot like Gordon Brown today

Nigel Lawson's budgets were models of clear-sighted vision. In every budget he cut taxes, simplified them, and abolished at least one altogether. A George Osborne budget seems more like one of Gordon Brown's, a patchwork quilt of little measures with no clear pattern to it.

– Madsen Pirie, President

The Chancellor’s deficit plan is in tatters

Mr Osborne’s deficit reduction plans for this Parliament always seemed improbable but lowered growth forecasts make this plain to see. At the current rate of cuts, he will now need to find £31bn of cuts or tax rises in the year 2019 alone to deliver his surplus. This is highly unlikely and it seems almost certain that he will end up breaking all three of his own fiscal rules. In all likelihood he does not expect to be in the job by then and doesn’t mind handing the problem to someone else.

– Sam Bowman, Executive Director

Cutting business rates for small businesses is a bad idea – and could Italify British businesses

Business rates are mostly a tax on landowners, not on firms. Even though firms write the cheques, when business rates are cut, rents rise in proportion, so firms are no better off, but landowners are. Reducing rates for small businesses only makes this problem even worse. Not only will rents rise across the board for all firms, big and small, there now is a large distortion in favour of smaller firms present in the rates system, akin to rules in slow-growing Eurozone states like France and Italy. Smaller firms are generally less productive than large firms, and by creating a large distortion in favour of inefficient small businesses the Chancellor is risking the "Italification" of British business.

– Sam Bowman, Executive Director

Corporation tax cuts are modest good news

Corporation tax is—as George Osborne said—one of our least efficient taxes, destroying huge amounts of economic activity for each pound it raises in revenue. Cutting it from its current rate to 17% by the end of the parliament will put upwards pressure on productive investment and on workers wages, though the move is small. Devolving the tax to Northern Ireland is also very welcome—currently there is a very strong incentive for firms to site themselves just across the border in the Republic of Ireland, purely in order to pay lower corporation tax. Equal corporation tax on either sides of the border would bring the UK more revenue, and increase efficiency by reducing arbitrary distortions on where businesses should locate.

– Ben Southwood, Head of Research

The soft drinks tax is the thin end of the wedge

A tax on sugary soft drinks is the first step on the road to fat taxes and sugar taxes more generally. It makes little sense to tax sugary drinks on their own, rather than sugar more generally – a couple of Mars bars are just as bad as a bottle of Coke – but the Chancellor probably reckons that the public won’t care if he only targets soft drinks. Once the tax is in place, he will follow the lead of other ‘sin taxes’ and raise it higher and higher, and impose it on more and more things. The costs of this tax will likely be passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices, so it will be regressive.

– Sam Bowman, Executive Director

Capital gains tax cuts are a return to normal

We should not exaggerate the chancellor's achievement with his capital gains tax cut, as he has only returned the main rate to the level enjoyed under New Labour, but it is nevertheless a step in the right direction. Reducing the returns to investment reduces investment, it's as simple as that, and most economists therefore oppose capital taxation. However, though the overall move is a step in the right direction, it also adds layers of complexity: lower rate taxpayers and entrepreneurs continue to pay lower rates, while housing and carried interest remains taxed at the old rate. Tax preferences for certain sorts of investment work against market signals, pushing cash towards areas it can do less good in.

– Ben Southwood, Head of Research

Raising the personal allowance is a good thing, but National Insurance thresholds have been left alone again

The Adam Smith Institute has campaigned for years to take the lowest-paid workers out of tax, and progress in raising the personal allowance is to be welcomed. But there has been no movement in National Insurance contributions, which are an income tax in all but name and kick in at much lower income levels than income tax now does – at just £8,060 per year. The Chancellor should target his income tax cuts on the poor and focus on raising National Insurance thresholds.

– Sam Bowman, Executive Director

The education changes will waste children's time and taxpayers' money

Announcing large, headline-grabbing education policy changes that were largely unrelated to funding in the budget would have been forgivable if there was evidence suggesting these moves would actually help much. But forcing kids to learn maths until 18, and stay in school until nearly 5pm, is going to cause lots of pain for little gain—Danish and Chinese evidence suggests that we'll see few if any benefits. Switching to an all-academy system, on the other hand, is probably a good move.

– Ben Southwood, Head of Research

Tax havens aren't quite the problem many seem to think

Yet another report from Oxfam shouting about the iniquities of inequality, the way in which tax havens rob governments of their rightful dues and....well, you get the story, you've heard it screamed at you often enough. But the real point to pick up from this is how unimportant that issue of tax havens actually is:

In a report titled End the Era of Tax Havens, Oxfam said wealthy people funnelling cash to “secrecy jurisdictions” such as the Cayman Islands and Bermuda were contributing to the wealth divide.

It said the Treasury was losing around £5bn a year from British “tax-dodgers” holding more than £170bn in tax havens.

It also highlighted the impact on the global wealth gap, saying governments are thought to be losing £120bn, with the world’s poorest regions missing out on £43bn.

£120 billion certainly sounds like a lot of money. But is it actually? In comparison to what?

The global economy is around $70 trillion, global tax revenues are some $23 trillion. Being generous with exchange rates we might say that the tax dodging (not that we accept the sum itself but let's work with what we're being given) is 1% of government budgets. So, who thinks that the world would be just peachy if governments had another 1% of revenue? How many problems does anyone really think this will solve? No, serious question.

Then think about the effort being being applied here. If 1% really is an important number then why not apply that same effort, or possibly less as it might actually be easier, in making governments just that 1% more efficient at what they do? We would have that same lovely outcome of making the world a better place but we'd have expended a great less energy in getting there. Odd then that the people shouting most about the havens aren't the people shouting about the efficiency with which the money is used really.

Leave aside all of the other arguments about tax and havens. Is 1% actually an important number?

The ASI's 2016 Budget Wishlist

Ahead of the Budget next week, here are the key reforms and tax cuts we hope to see the Chancellor announce: Scrap stamp duty on shares to boost investment

Stamp duty on shares may be one of the most harmful taxes we have despite raising relatively little money (£2.9bn in 2014-15). By making it costly for people to sell their shares, stamp duty interferes with price signals and raises the costs of investing overall. That hurts both savers and businesses’ access to investment financing. Scrapping it would be a cheap way of making stock markets direct money where it will be used best, give a boost to businesses in need of investment – and cement the City’s status as the world’s financial capital.

Pensions tax relief should be left alone

Abolishing the upper rate of pensions tax relief sounds like an easy way to save money, but it would be a huge mistake. Upper rate relief exists to help people smooth their incomes if they will only be in the upper tax bracket for a small part of their lives. Because people are taxed on pension withdrawals, abolishing upper rate relief would introduce double taxation to the system: people in the upper tax rate would be taxed for putting money in to a pension and again when they take money out of it. This would discourage some people from saving for their retirement and unfairly penalize the ones that do.

Alcohol duties should be merged into a simple alcohol tax

The alcohol duty system is amazingly complicated and confused, with entirely different rates per unit of alcohol for wine, beer, spirits, cider and sparkling wine, and strange kinks in the system that, for example, favour strong wines and ciders over weaker ones. This whole system should be replaced with a simple, flat per-unit tax on alcohol (as currently applies to spirits). That would stop the preferential treatment for selected drinks, like cider, and end the preferential treatment for stronger drinks. It might also make life a bit easier for Britain’s growing craft alcohol industry.

Phase out Housing Benefit altogether

Housing benefit should be phased out and eventually scrapped. In a property market where supply is tightly constrained, increases in housing benefit go mainly into higher rents. The empirical evidence suggests that about 70p of every £1 of the £26bn system goes into the pockets of landlords in the form of higher rents. Much of this benefit comes from renters who don’t even get the benefit, who are competed out. What’s more, the system encourages people with less means to move to the most expensive areas, since the level of payment is tied to prevailing rents, which means that the bill is artificially inflated. The government should use the money to supplement low incomes, by raising the employee NIC threshold and making the Universal Credit withdrawal rate less steep, so work pays more for UC recipients.

Stop business rates from taxing capital

Because business rates tax property values, they effectively tax both the land a property is built on, and the value of the bricks, mortar and some machinery on top of that land. Taxing land values is a relatively good way of raising revenue, because it does not discourage production. But taxing property discourages construction, improvements and investments in new machinery. The government should not exempt new machinery from business rates, as it is rumoured to be considering. This would add even more complexity to the system and increase compliance costs. And why should machinery, but not other improvements such as redecoration or refitting, be exempt? Instead, it should reform business rates so that they are based only on the unimproved value of the land the property sits on – and there is no reason not to improve the property itself.

Cut taxes, get money

It’s true: when you cut top tax rates, the rich pay more. UK Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne reports that his 2012 cut in the 50p-in-the-pound rate for top earners – to 45p – brought in an extra £8bn of revenue from those earning more than £150,000. It’s a prime example of the Laffer Curve (named after the economist Arthur Laffer): if you tax people beyond endurance, they will – one way or another – thwart you and pay less tax. And we have seen it all before, many times. In 1979 Chancellor Geoffrey Howe cut the UK's top rate of income tax from 83% (!) to 60%, Before the cut, the top 1% of taxpayers paid only 11% of the total take. By 1988 they were paying 14% of the total take. His successor Nigel Lawson cut top rates even more, from 60% to 40%, and receipts rose further. By 1997, the top 1% of earners paid a huge 21% of the total tax take.

Over in America, President Calvin Coolidge slashed top taxes too. As a result, revenues nearly doubled, and the share paid by $100,000+ earners rose from 28% in 1921 to 51% in 1925. Of course, top rates climbed again, but in the 1960s, President Kennedy slashed the highest rate from 91% (!) to 70%. As a result, the share paid by $50,000+ earners rose from 12% in 1963 to 15% in 1966, and total tax revenue grew from $69bn in 1964 to $96bn in 1968. Then in 1981, President Reagan introduced the largest tax cut in US history, cutting all taxes, and slashing top rates from 70% to 50%. In 1981, the top 1% of earners paid 18% of the tax take, but by 1988 they were paying 28%. President George H W Bush raised top taxes to help close the deficit: his move had exactly the opposite effect. But when George W Bush cut taxes, the economy powered ahead, and the tax take from million-dollar earners doubled from $132bn to $273bn in just two years.

It is a pity that, in 2012, George Osborne did not cut the top rate of tax from 50% to 40% – or even less – as we at the Adam Smith Institute advised him to do. He was still not confident enough to take on fully the ‘tax the rich’ arguments so deeply rooted in the psychology of envy. But the rich these days do not get rich from inheritance any more – check the Sunday Times Rich List to see that – they get it from building businesses that create jobs, customer value, and prosperity. A bolder cut would have raised even more revenue that enabled him to cut the deficit, and stimulated economic growth at the same time. Let’s hope he follows the evidence in his forthcoming Budget.

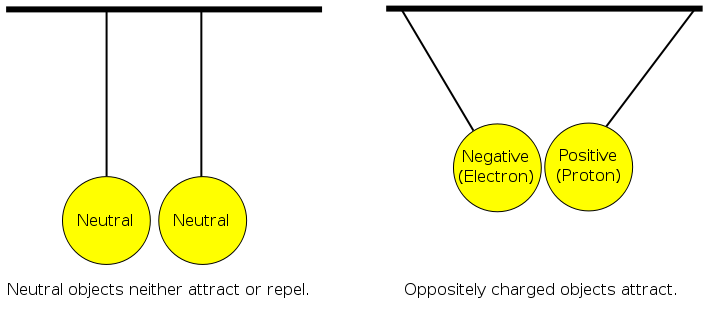

Among humans opposites don't attract

We don't think this is particularly surprising but it's nice to see confirmation:

The theory that opposites attract is a myth, scientists have found, after discovering that people are only attracted to those who hold the same views and values as themselves. In a finding hailed as a ‘paradigm shift’ for the understanding of relationships, researchers found that like-minded people will be drawn together but keep their distance from those who do not adhere to their beliefs.

This is not of course a paradigm shift, it's something obvious in the very art of our society. When opposites do attract then people write long stories about it: Romeo and Juliet and the subsequent retellings, West Side Story and Grease come to mind. And it's worth noting that that first comes to a somewhat sticky end (and we would also note that whether history works as tragedy and then farce stories definitely seem to move from tragic to musical to, well, farce).

However, rather than just advice on finding an inamorata this has significant implications for social mobility. For this is what leads to assortative mating, something which has been rather changing in our society in recent decades and also something which maintains social at least, if not economic, class divisions.

It has long been true that the aristos tend to marry aristos, the bourgeoisie the bourgeoisie, the proletarians the proletarians. Whether one thinks this good or bad it simply has been. However, it was also largely true that people married into one earner households. This somewhat limited income inequality when measured by household.

The situation is now rather different. People are marrying later and picking their mate from those they know at that sort of age. This means that we now tend to have lawyers marrying lawyers, professionals professionals, workers workers and so on. And most of us end up in two earner households: perhaps with a gap for the arrival of children but the majority of women do indeed work. This is leading to rather greater income stratification when we measure by household. For we end up with two professional income households, two middle income households, two worker income households and of course, down there at the bottom, single income households and none.

We entirely agree that there have also been other reasons for increasing income inequality: greater returns to education and globalisation for example. But at least some part of that increased inequality has come from the change in who we generally marry. Like has always attracted like: but rather more than used to be of this country it's less cultural or class like and now more economic like which is doing so. That's going to increase economic stratification.

There's also absolutely nothing at all any society with any pretensions to freedom or liberty can do about this. Not that we would want to but there's definitely those out there who would abjure any inequality stemming from any reason at all. We're not going to allow the State to interfere in that most personal of decisions, who we're to snore with for the next 50 years, nor can there be any justification at all for taxation on the basis of that choice (there's good reason why taxation is at the level of the individual, not the household). For this cause of inequality at least there is absolutely nothing at all that can or will be done.

We don't mind this at all, our political philosophy is based upon chacun a son gout anyway. But everyone else is just going to have to put up with it too.

We wish we had said this about inheritance tax

And in fact we have said things like this before:

Do you plan to leave your wealth to your children? Yes, on the understanding that they, in turn, protect it for their children and grandchildren, as I’m strongly against inheritance tax. Even at the height of my youthful Marxist fervour in the great socialist Jerusalem of the North West, I understood that the only real way to increase social mobility is to allow the working classes to keep the wealth they create and pass it on with their values, so that their children have the wherewithal – the money – to bring about change. Otherwise, you’re just giving it to out-of-touch politicians to waste and constantly pushing people off the mobility ladder.

Rather than the political classes taking a slice of the wealth each generation has created, then wasting it as is so often the case, why not a society in which wealth does cascade down the generations? We don't actually need to worry about the plutocratic fortunes: contra Piketty, absent those who pass on urban land through primogeniture those do get dispersed down the generations. What some thing of as great inherited fortunes (say, the current generation of Rothschilds) are in fact fortunes that have been generated again in that current generation.

So, why not a society in which that accumulated wealth of each generation is passed on to the children and grandchildren? A bourgeois society in which each is a sturdy independent yeoman, or one in the making?

We would hesitate to state that this is the entire and compete solution to anything at all, but what's wrong with it as a vision of future society? It doesn't look that unpleasant, does it, a world in which all have the resources to not be dependent upon the State?

How we know that the tax justice campaign is entirely rubbish

An interesting little whine in The Independent about corporate taxation. Which contains one gem and one great truth. The gem:

So enough of multinationals treating the British state as if it were a charitable fund to which they can voluntarily contribute. ... Their vans drive on taxpayer-funded roads, and they frequently avail themselves of a legal system paid for by you and I.

The roads are more than paid for by vehicle and fuel duties, both things which local and foreign companies pay if they do actually use the UK's roads. And the commercial courts system is paid for by user fees: it isn't actually true that you and I pay for it, not unless we avail ourselves of its services. but the great truth is this:

At a time when public trust in business is plummeting, tax justice has been called 'the Fairtrade of our times' - a measure by which we tell a good business from the bad. And as with Fairtrade, when co-ops were the first to stock the products, co-operative councillors the first to demand fairtrade procurement, and Labour & Co-operative MPs the first to demand political support, it's the co-operative movement and social enterprises that have once again been ahead of the curve.

We have nothing against cooperatives whatsoever, but we do against Fairtrade. For as we've found out it doesn't in fact benefit those poor producers very much if at all. It's simply a form of outdoor relief for the dimmer members of the upper middle classes, to whom all the actual money flows. And do note that it's nor us making the comparison between Fairtrade and tax justice but someone who supports both. And thus we know that tax justice isn't something either serious nor likely to be of benefit to us all: just as Fairtrade isn't and most certainly isn't to the poor.

Why taxes and snooker rules are not that different

Pretty much anyone with even the sketchiest understanding of economics knows that a competitive market is the mother of all driving forces for efficiency. In fact, Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu have a mathematical proof called the Arrow–Debreu model which shows that if the conditions are propitious in terms of a competitive free market there will be a general equilibrium between total supplies and total demands reflected in a set of prices. Obviously there are all sorts of reasons why the reality isn't the case, and that's largely due to all the ways in which politicians interfere with the natural mechanisms of prices (taxes and price controls are two prime examples). Like others at the ASI, I am not unfriendly to some form of government - but one of the primary rules of thumb is that in most cases an interference in the market that upsets the natural price mechanisms created by supply and demand is an inefficient interference.

For a more generalised indicator about when it is likely to be bad to interfere in the market in terms of negatively affecting people's behaviour, consider the game of snooker as an analogy. I used to play in two types of snooker league: the open league and the handicap league. In the open league both players would start the game on zero, and the best players had the best chance of winning. However, in the handicap league, based on a points system conditioned by past results, better players would give inferior players a head start in an attempt to narrow the gulf in ability and make the frames more evenly contested.

The handicap league works because even though the points are differentiated at the start of play, both players are still incentivised to try their hardest and play to the best of their ability. A handicap snooker league in which poorer players were given more of a chance by the better players being compelled to deliberately play below par would be no fun for either player.

The snooker handicap league can provide a pretty good illustration for when governmental interference in the market is good and when it is not. Policies that cause the participants in the market (snooker players) to waste opportunities (play below par) are likely to be bad policies, whereas any policies that cause as few wasted opportunities as possible (in a way that's similar to handicap scoring) are less likely to be bad policies (note: pretty much all taxes and price controls cause some loss of efficiency, so that's why I said 'cause as few wasted opportunities as possible' rather than 'cause no wasted opportunities').

To translate that in market terms, taxes or price controls that change behaviour in a way that diminish efficiency are undesirable. A price control on renting apartments is going to negatively affect property development and create a shortage (which ironically makes renting apartments more expensive). This is the snooker equivalent of making players play below their best ability. On the other hand, taxes like inheritance tax or savings tax or consumption taxes on goods to which consumers are relatively price insensitive, while not without some behaviour-changing costs, are more like the snooker equivalent of handicapping - they don't greatly diminishing anybody's drive to perform well. And let’s not forget, some taxes, such as taxes on negative externalities like pollution and congestion are taxes that can change our behaviour for the better.

The upshot is, whenever you consider a tax, a price control, a subsidy, or any other kind of government involvement in the market, it is good to consider whether it is a solution akin to adjusting the starting scores in a handicap snooker match, or whether it is akin to asking some snooker players to perform below the best of their ability. The closer that government involvement is to the latter, and the farther away it is to the former, the less good for society it probably is.

People are still very confused about the Google tax story

As a masterpiece of tripping over your own argument we think that this from The Observer takes some beating:

Recent wrangles between the European Union and the US on tax show how difficult achieving international consensus can be when competing interests are at stake. But it is possible: the EU is the most successful example ever of international co-operation.

Opinions obviously differ on how good the EU is at international consensus. But to use this argument when we are discussing Google's tax affairs does take some sort of chutzpah, possibly even ignorance:

Last week, the government chose to play both David and Goliath. George Osborne declared the deal UK tax authorities struck with Google to cover a decade of tax liabilities “a major success”, despite the fact that some estimates suggest this may represent an effective tax rate of just 3%.

The 3% number is nonsense of course. It is calculated by looking at the revenues that Google gains from sales in the UK and then applying their global profit margin. But if that's the sort of nonsense that people wish to use then why not humour them. And then ask, well, what rules are they that allow such a tax rate?

The rules that allow this are of course the European Union's own Single Market rules. Which give an absolute right for a company in any one EU country to sell in all EU countries and pay tax where the company is resident, not where the sales take place.

Some success in international co-operation and international consensus then. The organisation which is being praised is the one producing the initial problem being complained about.

Our own view is as we've said before. Corporations used to be a useful proxy as a place to tax the returns to investors, even with the unfortunate side effect of some of the economic burden falling upon workers. They are clearly no longer such a useful proxy so we should give up the pretense. Just abolish corporation tax altogether and simply tax people in their incomes and or consumption. At which point tens of thousands of tax experts have to go do something useful with their lives.

Such a pity, eh?