The Treasury, high on pre-budget coffee fumes, has floated the idea of removing tax relief on foreign investments on international ISAs. To the Treasury, this would increase investment in British companies, reviving our ailing capital markets and support equities. To everyone else, this would decimate wealth and growth opportunities. We hope that this is the Treasury launching kites and seeing what does not fly - without a doubt, this policy would slam straight back into the ground.

Not only is this an unpleasant return to mercantilism, the idea that we get wealthier by just keeping our money in the economy rather than from consumption and trade, but it would wallop households at a time of acute financial uncertainty.

Let’s step back and look at why this policy should be consigned to the shredder.

Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs) provide a tax-free account of up to £20,000 in tax savings for equity, bonds, and fund shares, and they have proved immensely popular. In 2022, ISAs had a market value of £741.6bn, with £459.8bn of that being in stocks and shares ISAs. This forms a solid base for participation in British capitalism and a core component of our financial and relatively high wealth.

No wonder the Treasury is hungry to divert a lot of this money into Britain’s markets.

However, by essentially tariffing international investment and outward FDI, British ISA holders will be left much worse off. As HMRC data shows, it’s everyday Brits who would be most affected. Over 6 million holders of ISAs are in the £10,000 to £20,000 income bracket, and a further 4.8m are in the £20,000 to £30,000 bracket, too. Those on low salaries, who use their ISAs as safety net pools of cash, or the almost £1bn a year withdrawn to buy a house, will be hit hardest.

Additionally, the scheme would create yet another barrier to the efficient allocation of capital. By removing tax relief on foreign investments ISA holders would be artificially incentivised to invest into less efficient UK firms.

This would be reasonable in a world without international trade, but when the UK imports 33 percent of all its goods consumed, it’s a bad idea. Investment in German cars, French wine and American oil will bring far greater gains, in terms of quality of product and price to UK consumers than investment into UK based alternatives. But this is exactly what such a policy would encourage. Free trade, allowing for the efficient allocation of capital not only within but across nations, has improved standards of living across the globe, it's what made Britain rich in the first place. Policy today should be encouraging this process, not restricting it to score political points.

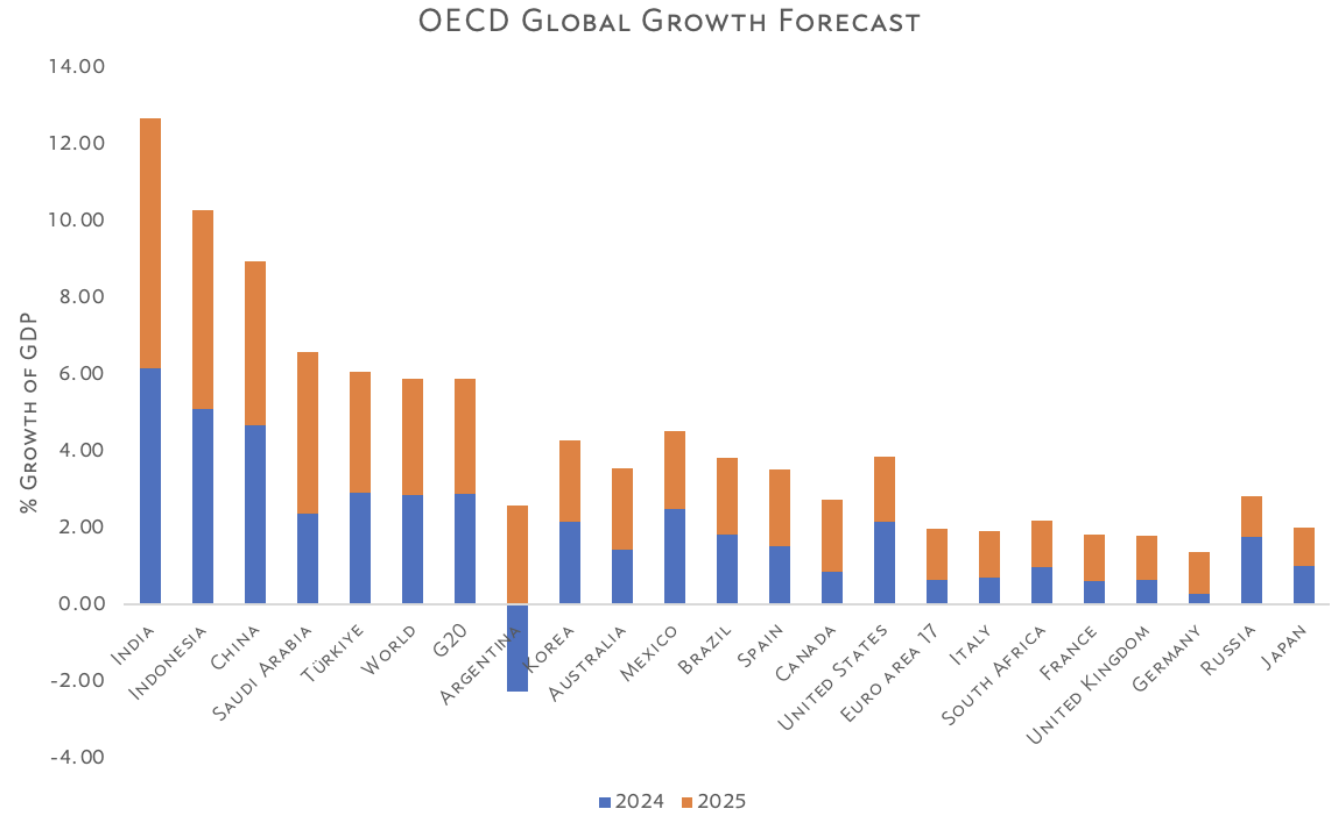

If the Treasury wanted a more British focussed financial product, they would do well to listen to UKFinance’s call for a British ISA, and advertise it widely. With UK households only holding around 11% of their assets in equities, compared to much higher percentages in the G7, this would be a fantastic opportunity for British savers. However, a tariff led approach to investment simply will not work. As ASI Senior Fellow Sam Bowman has pointed out, “The FTSE 350 is up 6% over the past five years. The S&P 500 is up 80%.” Why invest in Britain, when the world is giving much better returns?

The Treasury’s intention misses the fundamental causes for the lack of investment in UK equities markets, and instead looks for a quick fix which is destined to calamitously explode. We know that there isn’t enough liquidity in the system for firms to list in UK markets. Placing a tariff on outward FDI would only temporarily address this. Shortly after coming into effect, we would see a substantial bubble, inevitably set to burst when this capital floods the market and is poorly allocated.

What the UK needs to do to address weak equity market performance is to take a serious look at reforming the supply side of the economy, addressing cumbersome planning regulations that stop real business growth, sky-high energy bills which push ever larger bills through post boxes and then SMEs into bankruptcy, and the loathsome salaries that skilled workers can expect.

Liquidity is only one spoke of Britain’s mangled wheels. Indeed, liquidity is the result of well-functioning markets, not the other way around. Fixing our capital markets will take more than one poorly-thought out policy.

Finally, the big question is, how would this be enforced? It sounds, in the words of one financial stakeholder I spoke to, like a complete nightmare to manage. Whether retrospective, or going forward, the enforcement mechanisms would be byzantine, full of loopholes, and ultimately too expensive and ineffective.

As Adam Smith himself said: "The proprietor of stock is properly a citizen of the world and is not necessarily attached to any particular country. He would be apt to abandon the country in which he was exposed to a vexatious inquisition in order to be assessed to a burdensome tax and would remove his stock to some other country where he could either carry on his business or enjoy his fortune more at his ease."