Owen Jones tells us that Labour should, to beat the Greens, announce some really popular policy like re-nationalising the railways. And this might well be popular but perhaps not for the reason that people are assuming:

But there are three clear commitments Labour could offer to win over Green defectors. First, renationalise the railways. It would cut through like few other policies, and probably prompt some voters to break out in spontaneous applause. Polling demonstrates a publicly owned railway has near-universal appeal, winning over well-heeled Tory commuters and Ukip voters alike. But it also has a totemic quality about it: a clear demonstration that Labour has taken a decisive stance against the untrammelled market in the era of market failure.

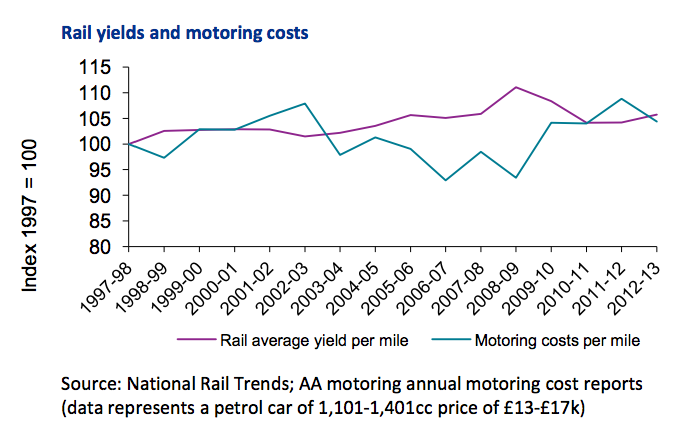

The real complaint, we feel, about the railways is not over who owns and or runs them. It's over the price of them.

It's common enough to see people complaining that UK ticket prices are among the highest in Europe. And they are, as a result of a deliberate political decision. More of the revenue to keep them running comes from ticket prices and less from direct subsidy than in most other countries. And that's the correct decision too. There's Britons who don't use a train from one decade to another: difficult to see why they should be taxed to provide cheaper transport for others.

And that's why nationalisation won't make much difference. Because doing so isn't going to reverse that decision that, by and large, people who use trains are the people who should pay to keep trains running. The only way ticket prices will come down is if the taxpayer gets dunned for it. And why should we?