Lorenzo is an intern at the Adam Smith Institute.

Some argue that the current UK welfare state discourages people to work, rather than specifically targeting low-income individuals.

An example of such policies are the Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) and the Income Support (IS) (Niemietz, 2010). As a matter of fact, these welfare-enhancing policies impose elevated implicit marginal tax rates on the most vulnerable segments of the labour market (Blundell et al., 1998; Meghir and Phillips, 2008), essentially functioning as an additional income tax for individuals receiving transfers who strive to go back to the labour market. Consequently, they give rise to detrimental effects on labour dynamics, as clearly highlighted in Table 1.

Adam et al. (2006) find indeed that, as the ratio of benefit income without work to disposable income in a low-paid occupation increases, the share of working adults strongly decreases. Despite recognising that there might not be a causal link between the two, the authors conclude that UK benefits might discourage job-seeking and return to work.

These policies extend economic support to a significant portion of the population including those who do not necessarily require it, rather than providing incentives for individuals with the lowest incomes to work and escape poverty.

As Table 2 shows, government transfers have evolved into a regular source of income across various income levels, as opposed to being limited to those with the lowest earnings (Office for National Statistics, 2020).

In 2019-2020, the 5th, 6th and 7th income decile groups, namely the middle and upper-middle class, received a higher percentage of benefits than the lowest decile group. This is mainly because the coverage of a spending programme, as opposed to its net distributional impact, is a much better predictor of its popularity (Niemietz, 2010).

The advantages of a Negative Income Tax

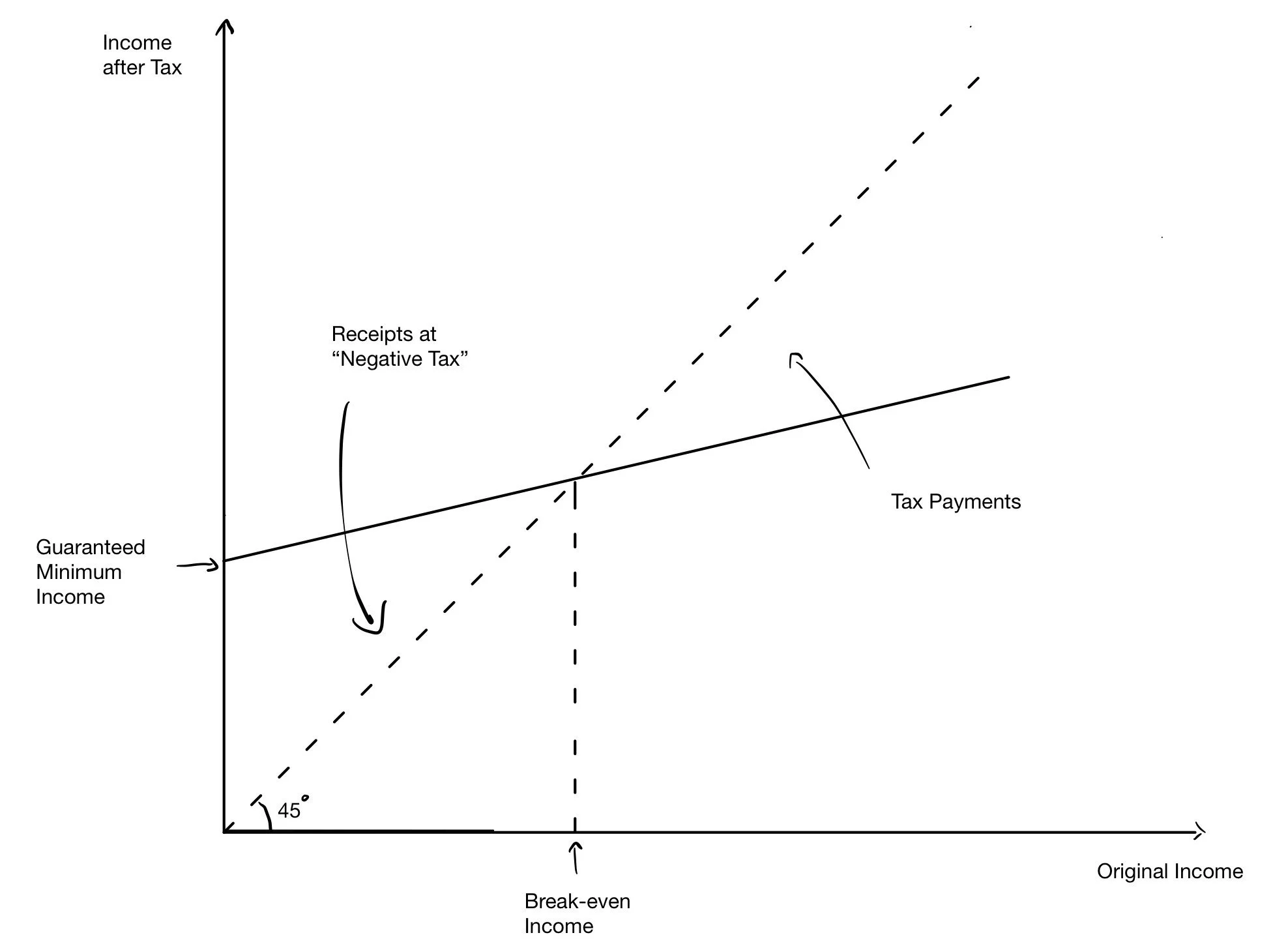

A negative income tax (NIT) supplements the incomes of the poor by achieving systematic structure of marginal rates, without poverty trap problems or cliff-edges. According to Friedman (1962)’s proposed scheme, at a “break-even” level of income, households pay no income tax (Figure 1).

Above this level, households pay tax at constant rate on each additional pound while, below this level, they receive a payment of such rate for each pound by which income falls short of the breakeven level tax.

This net benefit can therefore be considered a "negative" income tax as it makes the income tax symmetrical. Under such a proposal, some households would now pay no taxes, others would pay less taxes than before while other households with relatively high incomes would be unaffected (Tobin et al., 1967).

NIT’s main advantages are therefore claimed to be reducing poverty, supplementing the incomes of low-income earners, reducing expenditure on social security, welfare and administrative costs as well as contributing to the development of social capital (Humphreys, 2001).

Empirical Evidence

From 1968 to 1980, the U.S. Government conducted four experiments on the NIT, while the Canadian government conducted one, aiming to evaluate the policy's effectiveness and economic viability.

Some scholars argued in favour of the policy's success as the experiments did not find any evidence suggesting that a NIT would cause a portion of the population to withdraw from the labour force (Robins, 1985; Burtless, 1986; Keeley, 1981).

On the other hand, some scholars declared the failure of the policy based on two main arguments.

First, there was a statistically significant work disincentive effect for some subgroups such as primary earners in two-parent families, allowing scholars to conclude that a NIT discourages certain people to work.

Second, the work disincentive would increase the cost of the program of about 10 to 200% over what it would have been if work hours were unaffected by the NIT (Rees and Watts, 1975; Ashenfelter, 1978; Burtless, 1986; Betson et al., 1980; Betson and Greenberg, 1983).

Despite its theoretical economic advantages - reducing poverty by supplementing the incomes of low-income earners until they reach better paid work as well as lowering expenditure on benefits payments, welfare and administrative costs - further field research is required to assess NIT overall efficiency and economic feasibility.

Bibliography

Adam, S., Brewer, M. and Shephard, A. (2006) ‘Financial work incentives in Britain: Comparisons over time and between family types’, Working Paper 06/2006, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Ashenfelter, O., 1978. The labor supply response of wage earners. In: Palmer, J.L., Pechman, J.A. (Eds.), Welfare in Rural Areas. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Betson, D., Greenberg, D., (1983). Uses of microsimulation in applied poverty research. In: Goldstein, R., Sacks, S.M. (Eds.), Applied Policy Research. Rowman and Allanheld, Totowa, NJ.

Betson, D., Greenburg, D., Kasten, R., (1980). A microsimulation model for analyzing alternative welfare reform proposals: an application to the program for better jobs and income. In: Haveman, R., Hollenbeck, K. (Eds.), Microeonomic Simulation Models for Public Policy Analysis, vol. 1. Academic Press, New York.

Blundell, R.; Duncan A., Meghir, A., (1998) ‘Estimating labor supply responses using tax reforms’, Econometrica, 66, 4, 827-861.

Burtless, G., (1986). The work response to a guaranteed income. A survey of experimental evidence. In: Munnell, A.H. (Ed.), Lessons from the Income Maintenance Experiments. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Humphreys, J. (2001). Reforming wages and welfare policy: six advantages of a negative income tax. Policy: A Journal of Public Policy and Ideas, 17(1), 19-22.

Keeley, M.C., (1981). Labor Supply and Public Policy: A Critical Review. Academic Press, New York.

Meghir, C. and Phillips, D. (2008), ‘Labour supply and taxes’, Working Paper 08/04, London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Niemietz, K. (2010). Transforming welfare: incentives, localisation and non-discrimination. Institute of Economic Affairs.

Office for National Statistics (2020) “Working and workless households in the UK: April to June 2020”

Rees, A.,Watts,H.W., (1975). An overview of the labor supply results. In: Pechman, J.A.,Timpane, P.M. (Eds.),Work Incentives and Income Guarantees: The New Jersey Negative Income Tax Experiment. Brookings institution, Washington, DC.

Robins, P.K., (1985). A comparison of the labor supply findings from the four negative income tax experiments. Journal of Human Resources 20 (4), 567–582.

Robins, P.K., Brandon, N., Yeager, K.E., (1980). Effects of SIME/DIME on changes in employment status. The Journal of Human Resources 15 (4), 545–573.

Widerquist, K. (2005). A failure to communicate: What (if anything) can we learn from the negative income tax experiments? The journal of socioeconomics, 34(1), 49-81.