There's a lot of ruin in a nation

But ruin is not something in infinite supply in any nation:

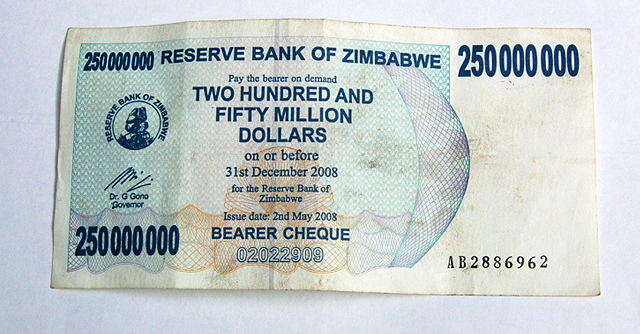

From Monday, customers who held Zimbabwean dollar accounts before March 2009 can approach their banks to convert their balance into US dollars, the governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, John Mangudya, said in a statement.

Zimbabweans have until September to turn in their old banknotes, which some people sell as souvenirs to tourists.

Bank accounts with balances of up to 175 quadrillion Zimbabwean dollars will be paid $5. Those with balances above 175 quadrillion dollars will be paid at an exchange rate of $1 for 35 quadrillion Zimbabwean dollars.

The highest – and last – banknote to be printed by the bank in 2008 was 100tn Zimbabwean dollars. It was not enough to ride a public bus to work for a week.

The bank said customers who still had stashes of old Zimbabwean notes could walk into any bank and get $1 for every 250tn they hold. That means a holder of a 100tn banknote will get 40 cents.

At some point simply running the printing presses does run into real problems. Our favourite little story from this whole disastrous episode comes from the final end days of the printed currency. Normally, currency printing is a very profitable occupation. Bit of paper, the price of some ink, and a banknote that is worth whatever the government says it is is created. Right at the end there it's said that the final decision to stop printing was taken because....no one would accept a bank note of any denomination at all, or any number of them, in return for supplying the ink with which to print the banknotes.

There have been hyperinflations before and it's a near certainty that it will happen again, somewhere. But this is the only example we know of where seigniorage was ridden all the way down to the bottom, to the bitter end.

The public wealth of nations

In 2013's Cash in the Attic ASI fellow Nigel Hawkins detailed £600bn of assets the government owned, but had never subjected to a market test. The paper recommended selling 10% of the assets off to begin with, in order to subject them to the market test and see if they were being best used, as well as giving the government money to reduce the national debt A new book, The Public Wealth of Nations, written by Dag Detter and Stefan Fölster, argues a lot of the same points—although with a much broader scope and deeper focus. The book's blurb runs:

When you look around the world it's almost as if Thatcher/Reagan economic revolution never happened. The largest pool of wealth in the world – a global total that is twice the world's total pension savings, and ten times the total of all the sovereign wealth funds on the planet – is still comprised of commercial assets that are held in public ownership.

And yet, while this is the largest pool of assets in the world, is also one of the murkiest – what goes on inside them is often not even properly known by the governments who own them. In most countries this vast portfolio is both a fiscal and political burden on society. If professionally managed it could generate an annual yield of 2.7 trillion dollars, more than current global spending on infrastructure: transport, power, water and communications.

Is there any reason why hospitals should own their buildings rather than rent them with long-term contracts? Outside of some historically-significant places couldn't the same be said for most public property. And how do we know whether an army barracks is well-placed if the army doesn't compete with other users over it?

The authors recapitulate their argument in a Citigroup note (pdf), with an introduction by Willem Buiter, going over their case for turning over government property to a properly-managed sovereign wealth fund.

As ever, the ASI is ahead of the curve!

Backing the 1%

I spoke last Thursday in the Cambridge Union on the motion, "This House Believes We Need the Richest 1%." I spoke in favour, giving 6 reasons for my support.

1. The richest 1% feature many people who have provided things to improve our lives.

These include Google, Amazon, Facebook, Paypal, YouTube, etc. We use them regularly and have propelled their developers into the top 1%. They made life easier, more interesting & more rewarding by providing services of value to others. Even the much-derided bankers have made capital work more effectively and made it more available.

2. The richest 1% act as an example to others.

People look at the careers of Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, & Mark Zuckerberg, and are themselves inspired to develop goods and services that will similarly be of use and value to others.

3. The top 1% pay taxes.

In the UK the 1% pay nearly 30% of all income tax. The top 3,000 UK earners pay more between them than the bottom 9 million. Their taxes support schools, hospitals and essential public services.

4. They give to charitable causes.

They are the mainstay of many medical & cultural charities. They fund art galleries, museums & symphony orchestras. They are helping to conquer disease and suffering. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is funding the eventual conquest of malaria, a disease that kills an estimated 2m people annually, including 500,000 children. Warren Buffet has issued the Giving Pledge, for rich people who pledge to give or leave half their fortunes to charity. Hundreds, including Bill Gates, have signed it.

5. The top 1% are early adopters.

They can afford to buy the new gadgets and try out the new processes. The ones that fall short of expectations drop by the wayside, but successful ones go into mass production, fall in price and become generally available. It was the 1% who bought the first large flat screen plasma and LCD TVs that are now commonplace and within reach of most people.

6. The top 1% include those who accelerate the pace of technological advance by putting their money behind adventurous developments.

Paul Allen made his fortune with Microsoft, and put $25m to back SpaceShipOne, winner of the X-Prize for the first private vehicle to carry people into space. Elon Musk made his fortune from Paypal, and used it to fund Tesla because he believes that electric cars can enable a cleaner world. He funded SpaceX, which sends Dragon capsules to the Space Station and is testing ways of landing and refueling its boosters. He does this to speed up accessible spaceflight.

With more time I could have added more reasons, such as the fact that the 1% help create most of the new jobs that replace ones automated or outsourced. I concluded by saying that the 1% help make the world a better, more colourful and more interesting place, and that the goods and services they make available enrich our lives.

Not the way to reform business rates

This is a cheeky little attempt here by the CBI:

The antiquated business rates system is a major barrier to investment and must be reformed, the Confederation of Business Industry (CBI) has urged. The CBI has recommended that smaller properties should be exempt from business rates, revaluations should be more frequent, and future increases should be limited as a result of a switch of the inflation benchmark which they track. The recommendations were made in a response by the industry body to a review of business rates announced by George Osborne, the Chancellor, in last year’s Autumn Statement. The industry body has recommended properties valued below £12,000 should be exempt from rates. The CBI has also called on the Government to reform its “decades-old” business rates model and shift towards raising the tax in line with the consumer price index (CPI), as opposed to the retail price index (RPI). Unlike CPI, RPI includes housing costs, which considerably inflates the rate and has largely fallen out of favour as an economic measure. Such a move could save UK companies £1.5bn, the CBI has said, and would ensure business rates do not outpace the official measure of inflation.

That's really not the point at all. Business rates are the closest thing to land value taxation that we have. As such they're pretty close to being the perfect tax (for we're always going to have government and thus do have to raise tax money somehow). And the point is that land (or at least land with the permission to build a commercial outlet upon) is the scarce thing. We thus want to tax that thing at its current market value. It is this which leads to the use of that scarce thing more efficiently.

It shouldn't actually be linked to an inflation measure at all: it should be linked solely to that underlying land value. But if it is going to be linked to an inflation measurement then it has to be to the one that includes that underlying land value, not the one that excludes it.

There is the other point of course. Which is that they're only arguing for this at a time when CPI is lower than RPI. As and when that reverses they'll be calling for a reversal. As has happened with things like cost of living increases in pensions. When wage growth is higher than inflation the government tends to link the increases to inflation. When wage growth is below inflation then the switch occurs to linking to wage growth.

So, of course, we could say that the CBI is just trying on what the politicians do routinely. To which the response is, come on CBI, you're not politicians and they are. Meaning that you're better than that.

UK loss on RBS sale: so what

Bygones are bygones. Or as economists call them, 'sunk costs'. If you invest in something that doesn't pay off, you can kiss your sunk costs goodbye. Just sell for what you can get. Today we are being told that UK taxpayers are going to take a £7bn loss when the government sells its stake in the the mega-bank RBS. Add fees and costs, and it might be £14bn. So what?

When the UK's Labour Chancellor Alastair Darling spent £45bn of our money bailing out RBS – and another £63bn on Lloyd's, Bradford & Bingley, Northern Rock and the rest – he wasn't going through the Financial Times with a highlighter to pick good investments to enrich taxpayers. He was trying to rescue Britain's financial services sector during the financial crash.

For a sector that brings in £66bn a year in taxation, that was a pretty good deal. Yes, you can argue that if he had done nothing, the market would have sorted it out. Or that the government should have simply lent the banks more money. But at the time it was all pretty hair-raising. Banks exist on trust, because if all their customers pull out at the same time the banks don't (usually) have enough cash on hand to repay their deposits. They have lent out that cash to help grow businesses, jobs and prosperity. So when 20,000 queued up to take their savings out of Northern Rock, and the RBS said its cash machines were going to run out of cash in 48 hours, it wasn't unreasonable to do something.

Actually, when you look at that £108bn went, taxpayers are already in pocket. Slices of Lloyd's have already been sold off, and Northern Rock is looking like a really good business again. It depends on your predictions of what the remaining bits are worth, but taxpayers could already be £14bn up on the deal. That's no surprise: the same happened in Sweden when its banking sector was bailed out years ago.

So what of RBS? Bygones are bygones. The bank grew bloated in the boom years, and has had to spend hundreds of millions restructuring. And being involved in just about sort of financial business known to humanity, it has picked up more regulatory penalties than most. So it is trading well below the 502p share price that Alastair Darling bought it at.

But that money was spent, not on buying a bank as an investment, but on buying a bank to save it from utter collapse. Money spent, job done. Bygones are bygones, let's move on.

Should we wait until things improve, so that taxpayers get all their money back? No. After all, as they keep telling us, shares can go down as well as up.

The world is not running out of resources after all, says new ASI monograph

The depletion of mineral reserves poses no serious threat to society, a new monograph published today by the Adam Smith Institute has concluded. “The No Breakfast Fallacy: Why the Club of Rome was wrong about us running out of resources” argues that outcries over resource availability from environmentalist groups are based on a misinterpretation of numbers and a misunderstanding of what mineral resources actually are.

The monograph, written by Adam Smith Institute Senior Fellow and rare earths expert Tim Worstall, says that groups that have warned about the world running out of rare mineral resources, such as The Club of Rome, have been using the wrong sets of data, mistaking the exhaustion of mineral reserves for the exhaustion of mineral resources.

Mineral reserves, the monograph explains, are simply the minerals that have been prepared for use for the next few decades; they are minerals that can be mined with current technology at current prices. Some reserves are going to run out in the near future, but this is a normal process. Every generation runs out of mineral reserves.

Mineral resources, however, refer to a concentration of minerals of a certain quality and quantity that have shown reasonable prospects for eventual economic extraction. These are much larger than mineral reserves.

Organic farming, for example, may be a useful idea, the monograph asserts, but the idea that it is a necessity because we’re about to run out of inorganic fertilisers is based on a falsehood. The reserves for minerals used in fertilizers may exhaust in the next few hundred years, but the exhaustion of resources is not estimated to occur for 1,400 years for phosphate and 7,300 years for potassium.

The report concludes that efforts to conserve and/or recycle mineral resources are wasteful and often end up being net harms to society, by diverting economic activity from more productive uses.

Senior Fellow at the Adam Smith Institute and author of the report, Tim Worstall, said:

We have a basic problem in our discussion of resource availability. Which is that most of the people in that discussion are grievously misinformed about what a resource is and how much of any of them we might have. It really is true that Paul Ehrlich, Jeremy Grantham, the Club of Rome, Limits to Growth and the rest are looking at the wrong numbers when they consider how much of any mineral or metal there is that we might be able to use.

This is not some arcane economic point. It is not some mystery explained only to the illuminati. Quite simply, most people assume that mineral reserves are what we have left that we can use. This is not so: mineral reserves are only what we have prepared for us to use in the next few decades. As such, it's really no surprise at all that mineral reserves are generally recorded as being going to last for the next few years.

This book explains this simply enough that even a member of the Green Party should be able to grasp the point. We are no more going to run out of usable minerals because we consume mineral reserves than we are to run out of breakfast because we eat the bacon in the fridge.

To read the full press release, click here.

George Osborne's political economy

These people are insane

Yet more from the anti-smoking fanatics:

Smoking costs the NHS at least £2bn a year and a further £10.8bn in wider costs to society, including social-care costs of more than £1bn, says the document. With the public health budget now set to lose £200m a year, the group says that the tobacco industry should pay an annual levy to offset those costs and assist with the effort of stopping young people picking up the habit as well as helping smokers to quit.

Peter Kellner, chair of the report’s editorial board and president of YouGov, said: “The NHS is facing an acute funding shortage and any serious strategy to address this must tackle the causes of preventable ill health.

“The tobacco companies, which last year made over £1bn in profit, are responsible for the premature deaths of 80,000 people in England each year, and should be forced to pay for the harm they cause,” he said.

Sigh, the tobacco companies do not cause that harm. Smokers, voluntarily, cause that harm to themselves and pay taxes through the nose for having done so. And yes, this is a liberal issue. We get to ingest as we wish, we get to kill ourselves with our habits if we so wish because we are free people.

But what raises this to insanity is that the most successful smoking cessation product anyone has ever come out with is the e-cigarette, or vaping. And those very same public health bodies are behind the move to ban the use of such things in Wales. Our apologies, but that really is insane.

Five reasons to support Osborne's budget surplus law

1. This law makes it harder for governments to run deficits when the economy is healthy. This is a sound approach to the public finances whatever you think the government should do during recessions. Both the Clinton and Blair governments ran surpluses for part of their time in power and they are usually praised for doing so. It's hard to think of a good argument against that. Keynes said in 1937 that, "The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity". 2. The law will not prevent deficit spending during recessions. The point is to make deficit spending the exception, not the rule. That also means that deficit spending is much easier if we think we need it – it's easier to go from 0% to -5% than from -5% to -10%. According to Keynesian theory it is the change in spending that matters, not the level. Advocates of fiscal stimulus should love this rule – it makes their policies much easier to implement in busts.

3. Yes, the law can be repealed by an Act of Parliament. So can any other law, that doesn't mean that they're irrelevant. There is inertia in politics and a government that is seen to repeal this kind of law will need a good reason for doing so. Making the public more aware of what's going on with government spending makes politicians more accountable.

4. Even if our models of economics told us that it was better for the government to have as much flexibility over spending as possible, our models of politics tell us that constitution-like rules are a good way of stopping abuses. This is about political economy as well as economics.

5. An honest Keynesian argument would be that the public is too ignorant and will oppose necessary deficit spending, so it's better to keep them in the dark. In this case the argument is simply that monetary policy is clearly and demonstrably just as or more effective than fiscal policy during recessions and depressions (indeed fiscal policy probably only 'works' through the monetary policy channel). The US cut fiscal spending by $85bn/year in 2013 (the "Sequester") which people like Paul Krugman warned would cost 700,000 jobs. Because monetary policy was accommodative under QE3, offsetting those cuts, this did not happen.

Thatcherism did actually make Britain richer, compared to everyone else

A new report by economists at Cambridge University’s Centre for Business Research purports to show that the post-1979 liberal reforms introduced by the Thatcher government did not boost the British economy. In a sense, that’s true. As the report shows, trend GDP growth and productivity were slower in the thirty years after 1980 than the thirty years before that. I hadn’t realised that this was new information, but OK.

The problem with the report is that it mostly looks at the UK in isolation. What it doesn’t mention is that this slowdown in trend growth was a global phenomenon. The real question should be how the UK did relative to the rest of the developed world.

Taking the US as a benchmark – the ‘technology frontier’ – the best any major economy can hope to do, basically – I’ve compared GDP per capita, adjusted for purchasing power parity, of France, Germany, Italy and the UK (German numbers include East Germany after 1991, so I’d more or less ignore them after that point). The UK is purple:

And here’s those countries’ relative performance, indexed to where they were in 1980. What we see is the UK's position basically not changing until 1980, with (West) Germany, France and Italy all converging on the US up to that point, then stagnating or declining slightly afterwards:

In this relative picture, the UK’s economic performance looks a lot better post-1980. There is a clear inflection point in the early 1980s where the UK begins to converge on the US, with GDP per capita as a percentage of the US's rising sixteen percentage points from 66% to 82% in 2010. In 1950 the UK GDP per capita was 69% that of the US's. The highest it was during the pre-Thatcher period was 73%, in 1961.

France, on the other hand, falls ten percentage points from 86% in 1980 to 76% today. Germany doesn't do much until the end of the 1980s, when political events render the data basically useless. Italy's decline tracks France's closely. In every case the UK improves relatively, and of course with the US at 100 the UK is improving relative to them, too.

This is probably mostly to do with labour force participation rates, not productivity. That might mask the true welfare situation: I might be much better off retiring early, but that would make me appear poorer and reduce GDP. But it still points to a large change that seems to have happened in 1980 that the report’s authors virtually ignore.

I say “virtually” because they do, actually, show this comparison in their report, it’s just hard to find. In a report with over thirty charts, all but one start during the postwar period. The only chart that doesn’t is this one – which, weirdly, starts in 1880. I cannot understand why, but it does make the UK’s relative recovery much more difficult to spot.

It is quite interesting that the Thatcher reforms don't seem to have boosted trend productivity by very much. As Pseudoerasmusnotes, there doesn't seem to be anything the UK can do to reach US levels of GDP per capita, and the Thatcher reforms only really brought Britain up to European levels of wealth. It looks as if boosting trend growth, not just playing catch-up, is really, really hard.