The BBC, Britain’s state-protected broadcaster, gets its funding from a tax of £145.50 on every household that possesses a TV capable of showing live broadcasts. That means live broadcasts from any broadcaster, so even if you never watch any BBC channels, you still have to pay. The exception is people over 75, who get their TV viewing for nothing because past governments ruled that television was an important source of companionship for the over-75s, many of whom live alone. This week it has been suggested that since the BBC is short of money, the over-75s should be asked to pay the licence fee voluntarily, even though they do not have to.

What a hopelessly mixed up policy this is. Firstly, Britain should not even have a state-sponsored broadcaster. It might have made sense in the 1930s when broadcast technology was new, and required fabulously expensive national infrastructure, but no longer. Increasingly, the BBC looks like a dinosaur among a growing number of independent and international broadcasters. But it has a near-monopoly grip over Britain’s media sector, of the sort that Rupert Murdoch can only dream of. Plainly, it should lose that protection and operate as a commercial broadcaster, using whatever mix of subscription and advertising it deems fit.

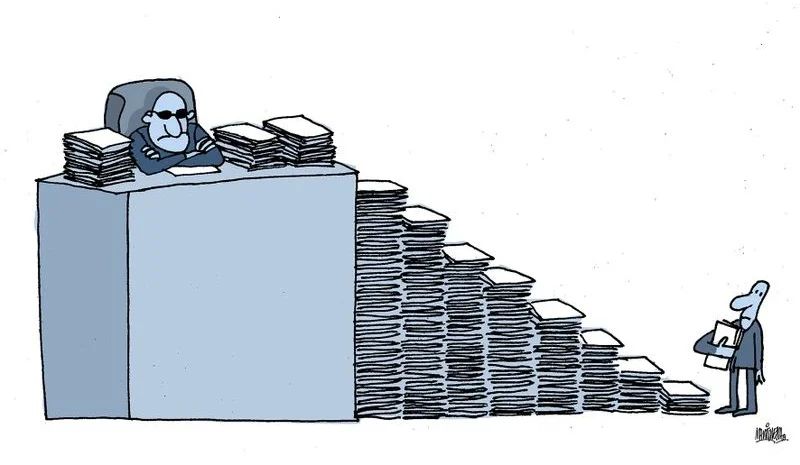

Not only should we not have a state broadcaster, nor should it be financed by what is in fact a poll tax on households. Nearly everyone has a TV, so the licence fee is more of a universal tax to support a state service, rather than a subscription for a broadcast package of your choice. And the same tax is paid by all households, rich or poor (apart from those comprising 75-year-olds, of course). So that is hardly a fair system either.

But if we are determined to keep this unfair license system and we really think it essential that people over 75 should be able to watch television without having to worry about the cost, there are better ways of doing it. One would be simply to raise the state pension by the equivalent £145.50 a year. At least then, the money would go to poorer households, because richer ones pay tax on their pension income. Again, the sate pension is an unfair and poor-value system (and it is also a Ponzi scheme, relying on current contributors to pay current pensioners), but this uplift would be better than what we have now.

There was a time when pensioners were, almost by definition, poor. That was the thinking behind making it universal at age 65 (for men, and 60 for women) when it was introduced in 1911. At that time, most people were in some form of manual labour, and by age 65 there was a fair chance that you were so exhausted by a lifetime of it that you could no longer do much useful work, and therefore could not support yourself. Today, however, pensioners are on average richer than the working population.

So it is certainly unfair to make the younger population pay to subsidise the TV viewing of everyone over 75, many of whom will be far richer than they. The Queen, and Rupert Murdoch, are both over 75: but why should a single mother in depressed Middlesborough pay higher taxes, or a higher licence fee, so they can get free television?

This is the kind of absurdity you get when things like broadcasting and pensions are run politically. Now we are trying to make the over-75s feel guilty for the absurdities that the political process has created. They should not fall for it.