A defence of sweatshops

Property rights and the wealth of nations

The International Property Rights Index, compiled by the Property Rights Alliance (based in Washington DC) and 92 partner think-tanks around the world, contains some interesting stuff. Finland tops the index, followed by Norway, New Zealand, Luxembourg and Singapore. At the bottom is (you guessed it) Myanmar, Bangladesh, Angola, Haiti and Venezuela. Indeed, the figures suggest a very strong and significant correlation (0.822) between a robust property rights system and GDP per capita. Countries in the top quintile of property rights scores have an average per capita income some 24 times higher than those in the bottom quintile. There is a positive but weaker correlation between property rights and economic growth, and property rights and foreign investment.

Interesting too is the result that the countries with the greatest gender equality, in terms of access to property rights, are again the richest, with Finland, Norway, New Zealand, Luxembourg, Sweden, Japan, Switzerland, Canada and the Netherlands topping the ratings. The countries with least gender equality feature many of the poorest, namely Bangladesh, Myanmar, Yemen, Libya, Angola and Nigeria.

So do countries have better property rights because they are rich, or do they get rich because their have better property rights? The remarkable decline of countries that have tried various brands of communism might give us a clue.

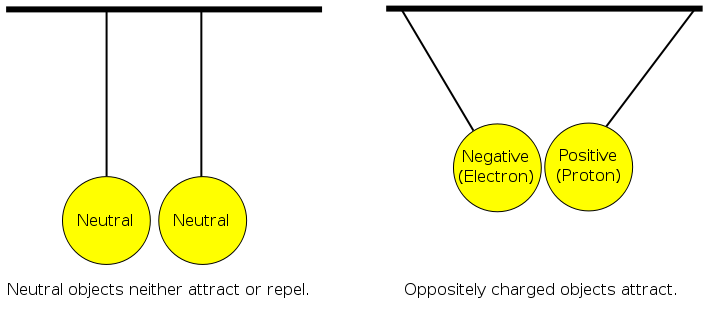

Among humans opposites don't attract

We don't think this is particularly surprising but it's nice to see confirmation:

The theory that opposites attract is a myth, scientists have found, after discovering that people are only attracted to those who hold the same views and values as themselves. In a finding hailed as a ‘paradigm shift’ for the understanding of relationships, researchers found that like-minded people will be drawn together but keep their distance from those who do not adhere to their beliefs.

This is not of course a paradigm shift, it's something obvious in the very art of our society. When opposites do attract then people write long stories about it: Romeo and Juliet and the subsequent retellings, West Side Story and Grease come to mind. And it's worth noting that that first comes to a somewhat sticky end (and we would also note that whether history works as tragedy and then farce stories definitely seem to move from tragic to musical to, well, farce).

However, rather than just advice on finding an inamorata this has significant implications for social mobility. For this is what leads to assortative mating, something which has been rather changing in our society in recent decades and also something which maintains social at least, if not economic, class divisions.

It has long been true that the aristos tend to marry aristos, the bourgeoisie the bourgeoisie, the proletarians the proletarians. Whether one thinks this good or bad it simply has been. However, it was also largely true that people married into one earner households. This somewhat limited income inequality when measured by household.

The situation is now rather different. People are marrying later and picking their mate from those they know at that sort of age. This means that we now tend to have lawyers marrying lawyers, professionals professionals, workers workers and so on. And most of us end up in two earner households: perhaps with a gap for the arrival of children but the majority of women do indeed work. This is leading to rather greater income stratification when we measure by household. For we end up with two professional income households, two middle income households, two worker income households and of course, down there at the bottom, single income households and none.

We entirely agree that there have also been other reasons for increasing income inequality: greater returns to education and globalisation for example. But at least some part of that increased inequality has come from the change in who we generally marry. Like has always attracted like: but rather more than used to be of this country it's less cultural or class like and now more economic like which is doing so. That's going to increase economic stratification.

There's also absolutely nothing at all any society with any pretensions to freedom or liberty can do about this. Not that we would want to but there's definitely those out there who would abjure any inequality stemming from any reason at all. We're not going to allow the State to interfere in that most personal of decisions, who we're to snore with for the next 50 years, nor can there be any justification at all for taxation on the basis of that choice (there's good reason why taxation is at the level of the individual, not the household). For this cause of inequality at least there is absolutely nothing at all that can or will be done.

We don't mind this at all, our political philosophy is based upon chacun a son gout anyway. But everyone else is just going to have to put up with it too.

The problem with Thomas Piketty

Perhaps more accurately, we should say one of the problems with the work of Thomas Piketty. As Brad Delong points out, the central contention is as follows: Hotshot French economist Thomas Piketty, of the Paris School of Economics, looked at the major democracies with North Atlantic coastlines over the past couple of centuries. He saw five striking facts:

First, ownership of private wealth—with its power to command resources, dictate where and how people would work, and shape politics—was always highly concentrated. Second, 150 years—six generations—ago, the ratio of a country’s total private wealth to its total annual income was about six. Third, 50 years—two generations—ago, that capital-income ratio was about three. Fourth, over the past two generations that capital-income ratio has been rising rapidly.

At first sight this is indeed a problem. The capital of our economy is what we produce our income from. If the capital to income ratio falls then that means we are using the capital more efficiently. If it rises, obviously and equally so, the economy as a whole is becoming less efficient at turning assets into income. However, we need to break this out into more than just "capital".

Using the work of Saez and Zucman we can see that at least on this side of the Atlantic the great capital concentration of the late 19th century was in the value of agricultural land. As the Americas, then the Ukraine, opened up this value fell precipitately. Thus the destruction of the great aristocratic landed fortunes.

The privately held value of financial instruments hasn't really changed all that much over the time period: and that's the bit we usually concern ourselves with when we talk about wealth concentration.

In more recent decades the two components of wealth that have risen again are private land holdings, and that is principally domestic housing and private pensions savings. Again, that privately held value of financial assets, outside those pensions, hasn't really risen nor has it become more concentrated.

So, yes, we've had a rise in the capital to GDP ratio. That part that is house price rises, well, we've had our say about that a number of times. It's the restriction on planning permissions which has driven up the value of land you may build upon. This is inefficient and we have suggested, again a number of times, that we should do something about it. Like destroy the system which artificially restricts, and thus drives up, the price of those permissions.

As to the private pensions this is actually something of a success story. Immediately post WWII someone retiring at 65 could and did expect perhaps 3 to 5 years in retirement before death. Nowadays the equivalent number is 15-20 and it's still rising. Fortunately we did also have a system of pension savings provision which has largely paid for this. That's an inefficiency in the capital to income ratio we can live with: because if we didn't have it then there would be many old people with no income to live upon.

Given that Piketty's observed facts are so easy to explain we don't really need to take much notice of his further worries. None of the above justifies a wealth tax, worries over the creation of a permanent haute bourgeoisie or any of those other fashionable concerns. Fix the planning system and celebrate pensions and we're done.

Once more into the breach on prostitution

We have yet another of these regular attempts to change the law on prostitution in the UK. To argue for change is fine of course: we don't think the current law is correct either. Yet the actual argument being put forward here is that we should switch to the Nordic (sometimes "Swedish") model. To understand this, at present in the UK, the selling of sex is not illegal: it's entirely legal in fact, as is the buying of it. Certain surrounding practices, soliciting (almost exclusively to do with street prostitution), living off immoral earnings (aka "pimping"), brothel keeping and so on are illegal. We don't think this is the correct structure of the law either. That Nordic system is that the selling of sex is not illegal, the purchasing of it is.

Caroline Bennett seems to be remarkably confused about the benefits of this:

Incidentally, with decreased supply, prices for sex have risen: witness a neat ledger shown to the commission by a Swedish state prosecutor, Lars Ågren, documenting the massive profits enjoyed, prior to discovery, by a Polish outfit running 23 prostitutes. “They could charge double in Sweden than in Poland.” He adds: “The girls aren’t making money.”

This is used as an argument in favour of the Swedish system as opposed to that Polish one. The Polish one being remarkably similar in law to the UK one. Pimping and brothels are illegal, the actual work itself is not. So, as Bennett herself says, the Swedish illegality of purchase seems to produce those profits for the managers of the trade, the pimps, but not benefit the actual people doing the work. Quite why this is an advantage of that system we're really struggling very hard to understand.

Our own attitude is more fundamental. Freedom, liberty, require that consenting adults get to do what consenting adults consent to. With the proviso that regulation of harm to others, those not directly involved or consenting (and obviously, those who are not adults) being entirely allowable, often sensible and sometimes necessary. To mangle Mill: their freedom to deploy their genitals as they wish stops where your genitals become involved, not before.

The correct form of the law is therefore very simple indeed. We do indeed say that any consenting adult may have sex with any other consenting adult as they wish. We do not regard the addition of cash payment to the process as changing this. Similarly, anyone may offer a massage to another for payment or not for payment. We do not regard the addition of erotic to this process as changing the basic liberty either. Thus the law should be that both the selling and purchase of sex should be, must be, legal, with whatever limitations necessary to protect those who are not adult and or who do not consent.

So just how should we inspire innovation?

We really would rather like to crack the secret of encouraging innovation. For it is the major determinant of how living standards are going to change in the long term. Thus having more innovation would be a good thing for the kiddies and thus we'd like to have more innovation. Yet the policies required to generate it are still a bit or an unknown. As James Pethokoukis over at AEI says:

Yet despite all that, the US still somehow creates more high-impact startups — innovative, disruptive new companies that grow big and make their founders superrich — than any other large economy. This is arguably a pretty good proxy for a nation’s innovative oomph and entrepreneurial spirit.

Sounds like a reasonable way to measure it to us. Although the people paid to ponder about innovation don't see it that way:

While the United States scores well in terms of refraining from using policies that detract from the global innovation system, its overall score is brought down by the fact that its contributions’ scores do not match those of leading innovation nations. The United States ranks just 17th on contributions. Most notably, the United States has weaker scores on tax policies that incentivize innovation (e.g., relatively weak R&D incentives, no innovation box, and no collaborative R&D tax credit), its lack of a national innovation foundation, and, in recent years, relatively faltering federal investment in scientific research. It speaks to America’s need to implement a more innovation-friendly corporate tax code, while at the same time increasing funding for science and technology.

Hmm, no, we think we'd probably read that the other way around. There's a currently trendy set of things that everyone is urged to have. Tax subsidies for innovation, federal scientific research and, obviously, a national innovation foundation where the people who recommend such things can sit and thing about foundational innovation. Nationally.

And it turns out that by far the largest rich economy on the planet does it just by allowing those who innovate successfully to keep their squillions. Seems simple enough to us, fire all the bureaucrats, lower the tax rate and watch that richer future approach at warp speed.

The terrors of the ISDS provisions in TTIP

We're really all rather mystified by the furore over the investor state dispute settlement system within the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Pact. Unite has been running a campaign insisting it will put the NHS at risk: foreign companies would be able to sue, outside our court system, if their profits from killing us all in our beds were interrupted. Others have been complaining that no future government could renationalise the railways if it came into force. The ISDS has absolutely nothing at all to do with either of those two cases. Nor, if truth be known, with most of what people are claiming about it. Here actually is the current text of what the EU is suggesting to the Americans.

Neither Party shall nationalize or expropriate a covered investment either directly or indirectly through measures having an effect equivalent to nationalisation or expropriation (hereinafter referred to as 'expropriation') except: (a) for a public purpose; (b) under due process of law; (c) in a non-discriminatory manner; and (d) against payment of prompt, adequate and effective compensation.

That is, any government can nationalise anything it wants. As long as all the usual rules about compulsory purchase and so on are followed: it's done legally, for some reason, it's not being done just to shaft someone and it is paid for. All things that we'd expect to be part of normal domestic law anyway, which are in fact part of normal domestic law anyway.

Thus we find it very hard to understand the demonstrations, the protests. There's nothing else in that draft that causes us the slightest concern either. That same clause even insists that it will not cover the compulsory licence of IP (say, a drug or a vaccine that a country cannot afford, under the usual WHO and WTO influenced rules).

We're left scratching our heads and the best we can come up with is as follows. And we will admit that we're not normally this cynical. It is obviously fun to go on a demo and if you choose the fashionable cause of the day that's where all the good looking people are going to be anyway. But in the absence of anything to have a good demo about there's still the need to all get together. And of course something like Unite needs to keep demonstrating (sorry) that it really is doing something for the workers in return for all those union dues. So, in said absence, why not create something to demo about? Doesn't matter how true or not anything is, whatever gets the juices flowing and shows continued the relevance of the organisers works just beautifully.

Sorry, we just can't think of any other reason why there's been this uproar. And read the full document for yourself to see if you can find it.

Pensions don't come for free

Toby Nangle has written a very good post on pensions, pointing out that Pay As You Go (PAYG) pensions and fully-funded pensions are similar in that they both represent the old having financial claims on the young. We can fund their pensions through taxing the young or by having them own financial assets. In his words:

Pensioners will collectively consume output produced by the young. Money, as always, mediates – and so in place of ‘consume output produced by’, read ‘receive income from’. Pensioners will receive an income that can come only from non-pensioners. This income could be in the form of rent, dividends, and interest only from the young, or the proceeds of asset sales made only to the young. This income could be in the form of tax transfers only from the young. Or some mixture. It was ever thus and it will ever be thus.

This is true, and a good point. But he goes too far in implying that this makes PAYG pensions and funded pensions similar overall, or that deciding between these two socially only involves practical questions. There are two huge differences.

- Inside a recession, when interest rates hit the 'Zero Lower Bound', extra consumption can increase aggregate demand. However, most of the time the economy is neither in a recession nor at the ZLB, and extra consumption comes at the expensive of extra saving (and saving is what goes into investment). Unless you are above the 'golden rule' level of saving—and this is very, very unlikely when there are so many taxes on saving and subsidies to non-saving (like providing retirement incomes) in our society—then extra saving (and investment) raises your productivity and living standards.Basically: if we force pensioners to save and invest to fund their retirements then when they actually do retire we have more capital, which means higher productivity and higher income. Thus, for any given level of retirement benefits, bearing it is an easier burden.

- Governmental claims can only be on your country's own citizens. Financial go all around the world. If you save a lot in your youth, invest those savings in foreign capital, and that capital earns a return, then your pensioners' claims could be on the young working citizens of another country—possibly one with a growing population! (NB having claims on the youths of another country doesn't necessarily make them worse off; if foreign investment raised a factory or funded training that made those citizens more productive then everyone can benefit.) Of course, this second point doesn't question Toby's story as a model for the world as a whole, just when we're considering individual countries separately—and since this is how pensions tend to be considered this is probably the way we should look at the question.

Yes, PAYG and funded pensions both involve bundles of financial claims. Yes, they might both be the same size, and one main difference is simply how the system is run and intermediated. But it does not follow that other differences are small or trivial; PAYG is likely to lead to a lower level of saving, investment, capital and income. Under PAYG, the burden of the elderly is heavier, because we have narrower shoulders.

Stepping into a wider world

Opponents of those inclined to vote to leave the EU often portray them as wanting to shut the UK off from the world and retreat into a narrow comfort zone. In fact the reverse is true for many of those I have spoken to. They regard the EU as a protectionist little backwater and want the UK to step into a wider world, dealing directly with many partners, and open to the world and its influences. Many countries outside the EU have negotiated trade deals with it that give them access to its markets and it to theirs. There is no doubt whatever that an important trading partner such as a non-EU United Kingdom would be able to do the same. More to the point is that a non-EU United Kingdom would be able to negotiate similar advantageous deals with other non-EU countries. EU countries have to let the EU negotiate on their behalf, blending their interests with those of the other members.

Some who want Britain to remain in the EU have warned that a 'leave' vote would constitute a leap into the darkness of uncertainty. Again, the reverse is more likely to be true. A vote to exit the EU would leave Britain able to have considerable influence on its own future, rather than having that future largely determined by other EU members.

There is no status quo. The EU is not static; it will not remain in the shape it has now. Many in the EU want "ever closer union." They want to be citizens of a country called Europe that has its own embassies around the world, its own police force and its own army. They want a Europe whose future is determined by a European Parliament and a European Prime Minister.

A UK that remains in the EU will not be able to prevent that; its voice and its voting power are too small. A non-EU United Kingdom would not be able to prevent that either, but it would not be a part of it. It would remain an independent United Kingdom, speaking or itself in the world's councils and representing its interests through British rather than European diplomacy.

It is false to suggest that the choice is between a UK connected to Europe and a UK that retreats into itself. The choice is between a UK that is a political part of the EU, and an independent UK that is connected economically to the EU, but able to deal with the wider world beyond the European Union.

The terrors of zero hours contracts

Forgive us but we do find this shouting about the evils of zero hours contracts to be really terribly amusing in one sense. For it is almost universally true that those writing the articles about the evils of zero hours contracts are themselves employed on zero hours contracts. Or, as it is also known, on a freelance basis and that just is the way that vast swathes of the media work:

What are zero-hours contracts? You asked Google – here’s the answer Dawn Foster

And off we go into a rather predictable Guardian rant about how awful such contracts are. Which then leads to our amusement, for when we examine the working life of the writer:

Dawn Foster is a writer on politics, social affairs and economics for The Guardian, London Review of Books, Independent and Times Literary Supplement, and is a regular political commentator for Sky News, Channel 4 News, and BBC Newsnight. Her first book, Lean Out, is on feminism, austerity and corporate culture.

Among us here at the ASI we have written for or appeared on near all of those outlets and the absolutely standard contract for all of them is a zero hours contract. It could be that this outpouring of protest is really a deeply buried attack on the media's own hiring practices, by those doing that very media reporting but we're really unsure as to whether people are being that Machiavellian. And observing the sharp elbowed jostle to gain absolutely any such work from any of those media outlets we really don't think people are protesting about their own employment.

Thus we're just left with the rather puzzling observation that zero hours contracts seem to be just fine for the middle class literati but obviously no one else should be allowed to enjoy the same employment structure. Which is, when you think about it, rather odd really.