Why do Tories like the NIT while Labour calls for a UBI?

In my previous blog, which you can find here, I investigated the economic rationale behind a Negative Income Tax (NIT) and a Universal Basic Income (UBI), arguing that the former exhibits greater effectiveness in combating poverty but might discourage individuals to work, while the latter incentives greater participation of low-income individuals in the labour market at the cost of a lower effectiveness in tackling poverty.

However, this economic assessment is not the only lens through which these two policies can be analysed and usually fails to explain why right-wing parties tend to support a NIT while left-wing ones prefer an UBI. This political divide is mainly to be connected to the ethical – rather than the economic- differences of the two policies, with a NIT relying on a libertarian view of freedom and equality while the UBI arising from an egalitarian one.

The first key aspect that distinguishes the ethical foundations of NIT and UBI relates to their perspectives on freedom. Examining freedom from a negative standpoint involves considering an individual free when they can carry out their actions without interference from others or groups (i.e., they are free from). Emphasising the concept of negative freedom is intrinsic to libertarian thinking, as it necessitates the establishment of minimal legal frameworks and a governing authority to safeguard individuals' self-determination.

In contrast, from an egalitarian standpoint, an individual is deemed unfree if they lack the means necessary to pursue a goal and be autonomous, even if no other individual or institution obstructs their path. Positive freedoms can therefore be described as opportunities (i.e., they are free to), and their maximisation necessitates redistributive measures, which are ensured by a stronger and more active state.

A second factor is individuals’ approach to uncertainty. On one hand, the libertarian stance acknowledges that different individuals possess varying degrees of risk aversion when engaging in economic activities. This implies that individuals make choices regarding their employment status, investments, and consumption based on their unique risk preferences. In this view, the market system ensures equality of treatment among individuals.

On the other hand, the egalitarian viewpoint perceives and justifies redistribution as a response to the widespread risk aversion exhibited by all individuals. This argument is rooted in the notion that, given individuals' lack of knowledge beyond moral considerations (referred to as the veil of ignorance), they would collectively support the existence of institutions dedicated to redistributing the products and benefits stemming from the arbitrary distribution of abilities and talents.

Based on a libertarian view, a negative perception of freedom and a probabilistic approach to uncertainty would reject any form of equality beyond equal rights, thus opposing any form of compulsory fiscal imposition. However, assuming the necessity for the existence of such a policy, state intervention should be limited to preserving the essential tenets of libertarianism.

Therefore, any public redistributive scheme should exclude any form of needs, the link with the market should be as weak as possible and the role of the state should be as less invasive as possible. In this context, a NIT scheme is often argued to be a redistributive policy that adheres to these constraints by implementing exemptions and deductions from taxable income and only taxing the portion that exceeds a certain threshold. On the other hand, a positive perception of freedom, which asserts that true freedom encompasses both the means and the rights to pursue one's desires, along with a risk-averse approach to uncertainty, leads to a policy that addresses people's needs with an unconditional requirement. This is exemplified by a UBI, which aims to meet individuals' purchasing power without imposing specific conditions.

Ah, so wind power's not so cheap then, eh?

Back the drawing board then, eh?

Energy bills will rise £200 a year within a decade to pay for wasted wind power as new turbines in Scotland are paid to switch off, according to new forecasts.

Poor electricity grid infrastructure means energy created by turbines in Scotland cannot reach homes in England on very windy days.

Last year Britain wasted enough wind power for a million homes, but new turbines built over the next decade would see that figure grow fivefold by 2030, according to think tank Carbon Tracker.

The cost to pay wind farms to switch off at these times and buy gas to fill in the shortfall would rise to £3.5 billion a year, according to Carbon Tracker’s analysis. That would add an average of £200 to annual household energy bills.

Once we add in dispatchibility and transmission costs then wind isn’t so cheap. But then we all know that already, even if the others haven’t grasped it as yet.

The much more interesting part of this is something more meta.

The problem has been blamed on bottlenecks in the planning process which can take up to seven years for major new electricity cable projects.

Think on this. The same people who are insisting that we’ve got to entirely redesign the whole economy - or, the milder ones, the entire power sector - are likely the same who insist we’ve got to have lots and lots of planning. The planning being the thing which obstructs the ability to do that redesign of course. For the one thing the planning permissions sector does is make it damn near impossible to do anything different. But the whole point of the redesign is that everything must be done different.

That is, the last 30 years of planning law is what is making it so difficult to carry through the plans of the past 30 years.

There is one theory of history which states that every society starts out vibrant and active and this lasts until it drowns in its own bureaucracy. At which point the fall and the rise of a new civilisation. Given that we do actually know this is possible we suggest, ever so gently, that perhaps we could - should - short circuit this process and instead drown our own bureaucracy?

NIT or UBI, that is the (economic) question

The Negative Income Tax (NIT) and the Universal Basic Income (UBI) schemes are often mistakenly interpreted as the two sides of the same coin. This is mainly because both policies aim at tackling poverty through redistributive taxation. However, both from an economic and ethical standpoint, these two policies present differences that should not be disregarded.

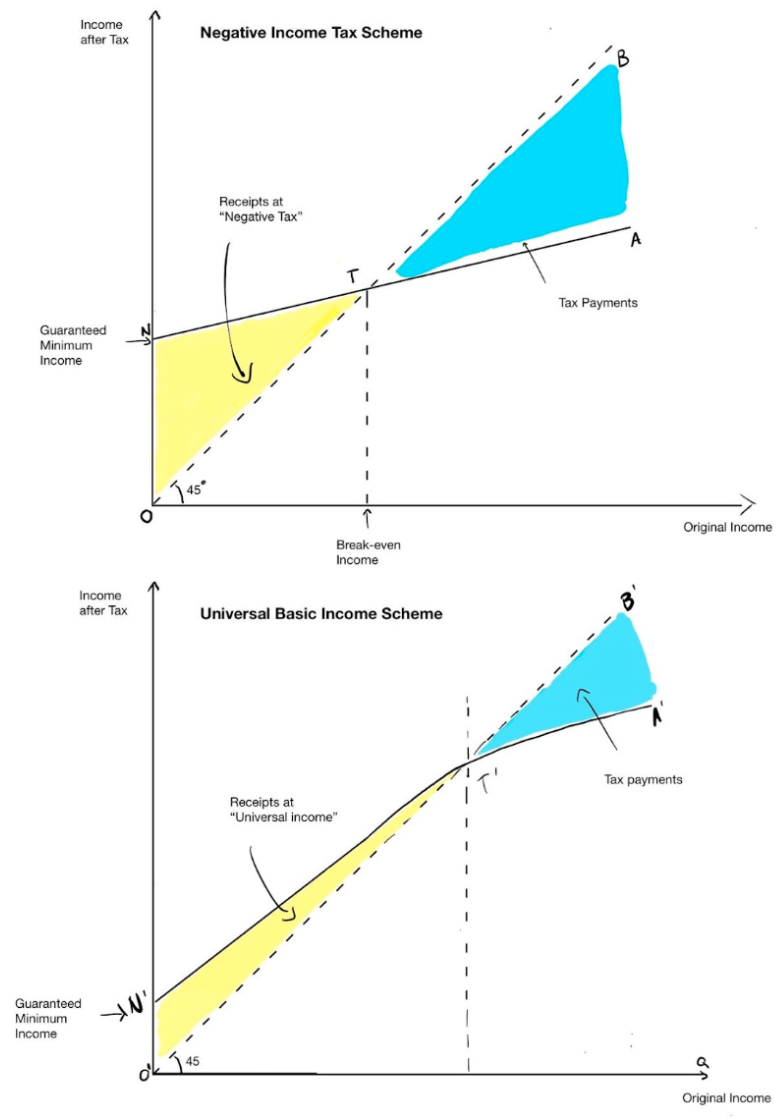

Economically, a NIT can be understood as a tax system associated with a tax deduction, as it proposes a scheme where at the “break-even” level of income, households pay no income tax. Above this level, households pay tax at a constantly increasing marginal rate on each additional pound while, below this level, they receive a payment of such rate at an inverse ratio. In the case of NIT, we can therefore observe a tax transfer (represented by the area NTO in Figure 1) that diminishes as income increases at a rate of -t and becomes zero when an individual’s income reaches the threshold T. Once income surpasses this threshold, taxpayers begin to pay a positive tax, quantified by the area TAB.

On the other hand, the UBI scheme entails the regular distribution of a uniform cash payment to individuals, irrespective of age, without any conditions attached. Realistically, a millionaire will receive the same payout as those currently on Universal Credit. Hence, in the case of UBI, the implementation of a universal and unconditional transfer ON’ to all individuals causes a permanent shift along the 45° line. Following the redistribution, individuals with a gross income below OT’ receive a positive benefit resulting from the disparity between the sum of UBI (represented by ON’) and the taxes paid, measured by the vertical gap between the translated 45° line and the income paid by the firm. Conversely, taxpayers with an income exceeding OT’ will incur a net tax payment.

Figure 1: Economic assessment of NIT and UBI

To ensure that the total benefits provided by a NIT and UBI program are equivalent, the area ONT in the NIT scheme must equal the area ONT’ in the UBI scheme, considering a normal distribution of individuals.

As clearly evident in Figure 1, a NIT scheme benefits individuals with low pre-tax income, but beyond the threshold T, it disadvantages individuals who would receive a higher disposable income under the UBI option. By ensuring equal net costs for both schemes, in a NIT scheme, a minority of poor individuals is therefore supported by middle and high-income taxpayers whereas, in a UBI one, wealthier individuals contribute to redistributing income to middle and low-income individuals. A NIT program has therefore a more pronounced impact on reducing labour supply among low-income earners compared to UBI. From a distributive perspective, NIT exhibits greater effectiveness in combating poverty, but the presence of high marginal tax rates on low incomes might discourage the same individuals to work. Conversely, in the case of UBI, the lower benefits for impoverished individuals, coupled with lower marginal tax rates, incentivize greater participation of low-income individuals in the labour market at the cost of a lower effectiveness in tackling poverty.

Let us all praise the planners

Apparently we should all be installing heat pumps real quick and right now. Germany’s Greens seem to have a problem with doing so:

Germany’s Greens are facing ridicule over reports that they have failed to install a heat pump in their party HQ, despite pushing for a nationwide switch to the technology.

A project to install the device at the eco-party’s headquarters in central Berlin has taken three and a half years because of a variety of problems that include difficulties finding qualified tradesmen and a two-year wait for a drilling permit, Der Spiegel magazine reported.

OK, so that’s just a ha ha, gurgle sort of observation. Even though it has obvious implications for the current insistence that everyone in this country must have one immediately. But those planners are not done yet:

Households have been saddled with three million faulty smart meters in a botched roll-out that is ballooning over budget, a report reveals today.

It had to be done quickly, you see? But that’s OK, it was really important and ministered by those planners so nothing could go wrong, could it? Rolls Royce minds and all that?

But of course these are mere trivia. Except, well, no. Those first generation biofuels not only starved the poor they had higher emissions than fossil fuels. The idea that Drax burning North American woodchips is CO2 neutral is laughable. Although for a real bellyacher try the Germans again, who actually have torn down a wind farm to get at the cheap brown coal, the lignite, underneath.

The connecting point here is that the planners aren’t very good at planning. Therefore we shall have to stop using planners.

This is entirely different from the logical points usually made about planning - that it’s impossible to have the information, all that Hayek and Nobel Lecture stuff. Instead it’s just the simple observation that our society has put the dullards into the planning offices. Best to keep them safe there and us out here safe from them by not using planning.

Britain's less productive because we're going green

British productivity numbers have not been doing well these recent years. As we all also know we’ve been building out those renewables over that same time period. These two things are connected. In fact, the one is causing the other.

Just to remind, productivity is the value of output divided by the number of labour hours. This means that if labour is used to produce something more valuable then productivity is going up. It also means that if more labour is used to produce something of the same value then productivity goes down. The other thing to know is that while productivity isn’t everything it is, in the long run, pretty much everything as a determinant of lifestyle and wealth. Rising productivity makes us richer.

The IMF has thoughts on this (page four, here). Coal and natural gas require 0.21 job years per GWh of electricity produced. Wind requires 0.32. Replace coal and gas with wind power and productivity declines and we get poorer.

No, this is not arguable. This is simple fact. It might be worth it to save Gaia, that’s at least logically possible. But it is indeed simply true that wind requires more labour therefore lowers labour productivity. Of course, by the same standard, solar requires 1.5 man years so solar is one seventh as productive as coal or gas.

So, what have we been doing recently? Closing down coal and gas in favour of wind and solar. We’ve been deliberately reducing labour productivity.

As we say, maybe this is worth doing for Gaia. But there are those out there who have the nerve to complain about the productivity numbers - exactly the same people who desire those renewables. That’s just damn cheeky. Worry about one or the other by all means, but don’t demand the one then complain about the results of your own insistences.

Do you want NITs?

Lorenzo is an intern at the Adam Smith Institute.

Some argue that the current UK welfare state discourages people to work, rather than specifically targeting low-income individuals.

An example of such policies are the Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) and the Income Support (IS) (Niemietz, 2010). As a matter of fact, these welfare-enhancing policies impose elevated implicit marginal tax rates on the most vulnerable segments of the labour market (Blundell et al., 1998; Meghir and Phillips, 2008), essentially functioning as an additional income tax for individuals receiving transfers who strive to go back to the labour market. Consequently, they give rise to detrimental effects on labour dynamics, as clearly highlighted in Table 1.

Adam et al. (2006) find indeed that, as the ratio of benefit income without work to disposable income in a low-paid occupation increases, the share of working adults strongly decreases. Despite recognising that there might not be a causal link between the two, the authors conclude that UK benefits might discourage job-seeking and return to work.

These policies extend economic support to a significant portion of the population including those who do not necessarily require it, rather than providing incentives for individuals with the lowest incomes to work and escape poverty.

As Table 2 shows, government transfers have evolved into a regular source of income across various income levels, as opposed to being limited to those with the lowest earnings (Office for National Statistics, 2020).

In 2019-2020, the 5th, 6th and 7th income decile groups, namely the middle and upper-middle class, received a higher percentage of benefits than the lowest decile group. This is mainly because the coverage of a spending programme, as opposed to its net distributional impact, is a much better predictor of its popularity (Niemietz, 2010).

The advantages of a Negative Income Tax

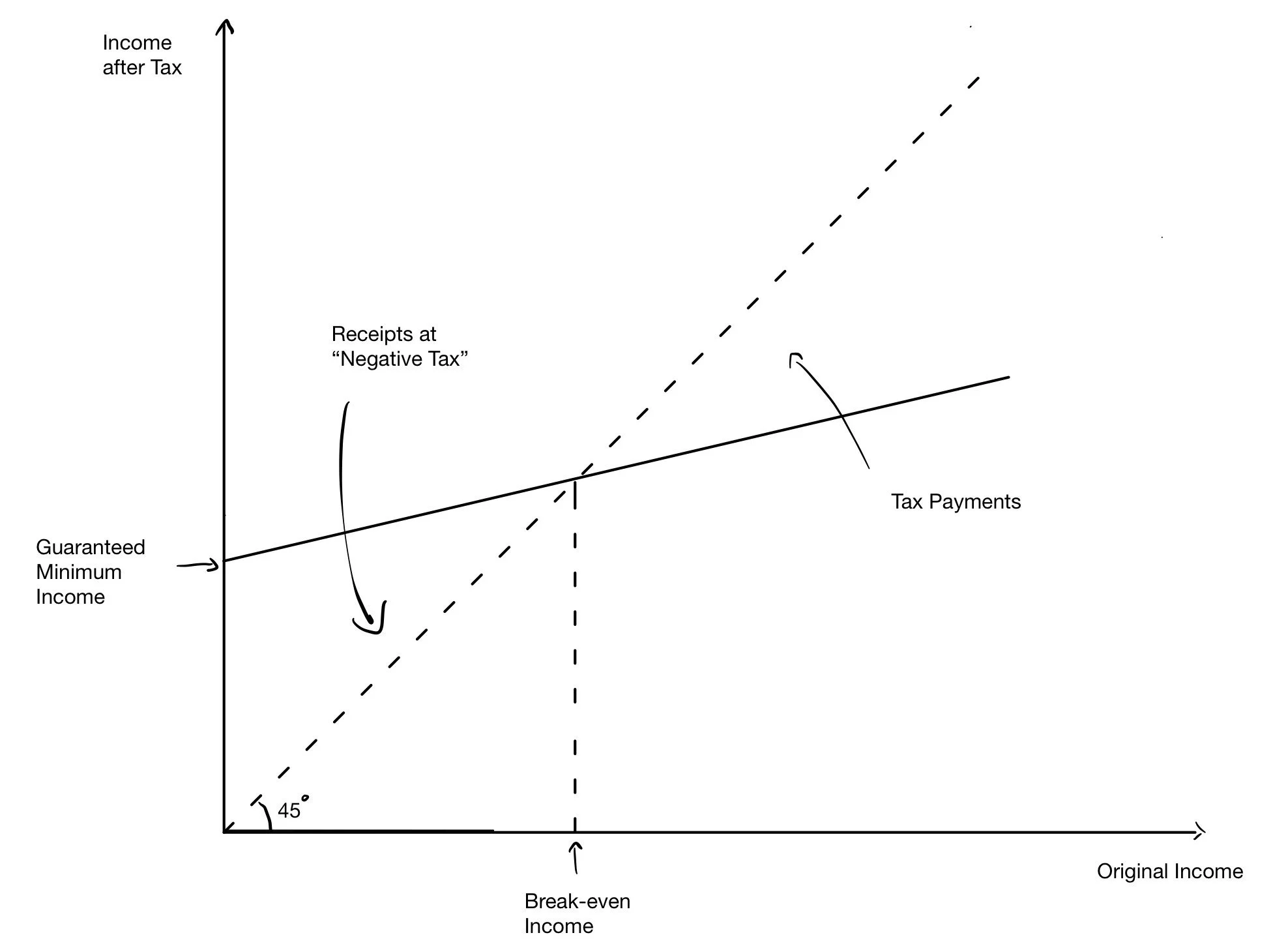

A negative income tax (NIT) supplements the incomes of the poor by achieving systematic structure of marginal rates, without poverty trap problems or cliff-edges. According to Friedman (1962)’s proposed scheme, at a “break-even” level of income, households pay no income tax (Figure 1).

Above this level, households pay tax at constant rate on each additional pound while, below this level, they receive a payment of such rate for each pound by which income falls short of the breakeven level tax.

This net benefit can therefore be considered a "negative" income tax as it makes the income tax symmetrical. Under such a proposal, some households would now pay no taxes, others would pay less taxes than before while other households with relatively high incomes would be unaffected (Tobin et al., 1967).

NIT’s main advantages are therefore claimed to be reducing poverty, supplementing the incomes of low-income earners, reducing expenditure on social security, welfare and administrative costs as well as contributing to the development of social capital (Humphreys, 2001).

Empirical Evidence

From 1968 to 1980, the U.S. Government conducted four experiments on the NIT, while the Canadian government conducted one, aiming to evaluate the policy's effectiveness and economic viability.

Some scholars argued in favour of the policy's success as the experiments did not find any evidence suggesting that a NIT would cause a portion of the population to withdraw from the labour force (Robins, 1985; Burtless, 1986; Keeley, 1981).

On the other hand, some scholars declared the failure of the policy based on two main arguments.

First, there was a statistically significant work disincentive effect for some subgroups such as primary earners in two-parent families, allowing scholars to conclude that a NIT discourages certain people to work.

Second, the work disincentive would increase the cost of the program of about 10 to 200% over what it would have been if work hours were unaffected by the NIT (Rees and Watts, 1975; Ashenfelter, 1978; Burtless, 1986; Betson et al., 1980; Betson and Greenberg, 1983).

Despite its theoretical economic advantages - reducing poverty by supplementing the incomes of low-income earners until they reach better paid work as well as lowering expenditure on benefits payments, welfare and administrative costs - further field research is required to assess NIT overall efficiency and economic feasibility.

Bibliography

Adam, S., Brewer, M. and Shephard, A. (2006) ‘Financial work incentives in Britain: Comparisons over time and between family types’, Working Paper 06/2006, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Ashenfelter, O., 1978. The labor supply response of wage earners. In: Palmer, J.L., Pechman, J.A. (Eds.), Welfare in Rural Areas. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Betson, D., Greenberg, D., (1983). Uses of microsimulation in applied poverty research. In: Goldstein, R., Sacks, S.M. (Eds.), Applied Policy Research. Rowman and Allanheld, Totowa, NJ.

Betson, D., Greenburg, D., Kasten, R., (1980). A microsimulation model for analyzing alternative welfare reform proposals: an application to the program for better jobs and income. In: Haveman, R., Hollenbeck, K. (Eds.), Microeonomic Simulation Models for Public Policy Analysis, vol. 1. Academic Press, New York.

Blundell, R.; Duncan A., Meghir, A., (1998) ‘Estimating labor supply responses using tax reforms’, Econometrica, 66, 4, 827-861.

Burtless, G., (1986). The work response to a guaranteed income. A survey of experimental evidence. In: Munnell, A.H. (Ed.), Lessons from the Income Maintenance Experiments. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Humphreys, J. (2001). Reforming wages and welfare policy: six advantages of a negative income tax. Policy: A Journal of Public Policy and Ideas, 17(1), 19-22.

Keeley, M.C., (1981). Labor Supply and Public Policy: A Critical Review. Academic Press, New York.

Meghir, C. and Phillips, D. (2008), ‘Labour supply and taxes’, Working Paper 08/04, London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Niemietz, K. (2010). Transforming welfare: incentives, localisation and non-discrimination. Institute of Economic Affairs.

Office for National Statistics (2020) “Working and workless households in the UK: April to June 2020”

Rees, A.,Watts,H.W., (1975). An overview of the labor supply results. In: Pechman, J.A.,Timpane, P.M. (Eds.),Work Incentives and Income Guarantees: The New Jersey Negative Income Tax Experiment. Brookings institution, Washington, DC.

Robins, P.K., (1985). A comparison of the labor supply findings from the four negative income tax experiments. Journal of Human Resources 20 (4), 567–582.

Robins, P.K., Brandon, N., Yeager, K.E., (1980). Effects of SIME/DIME on changes in employment status. The Journal of Human Resources 15 (4), 545–573.

Widerquist, K. (2005). A failure to communicate: What (if anything) can we learn from the negative income tax experiments? The journal of socioeconomics, 34(1), 49-81.

It's never us that's the problem, is it, it's always them, the other

Apparently climate change is all the creation of a few fossil fuel company billionaires and entirely nowt to do with any of us:

It makes sense that anyone facing conditions as awful as those caused by the smoke this week would get angry. The trick is to get angry at the right people: fossil fuel billionaires who couldn’t care less about the horrors they’ve unleashed.

We’ll leave aside the obvious logical comparison here for simple good taste reasons, but there’s a definite side of human nature that wants to blame everything that goes wrong, whatever goes wrong, on that other. It’s them over there, not us. No, really - they’re to blame, just couldn't be cute and cuddly us now, could it?

Varied attempts have tried to blame things on the Trots, the bourgeois, wreckers, whites, colonialism, The English, Rosicrucians and the Illuminati. But climate change, whatever we might think of how bad it is or isn’t, isn’t something being done to us - certainly not us rich world folk. It’s something we’re doing.

Consumer demand fuels these companies’ decisions, to be sure.

Well, yes. Without the demand to be able to transport ourselves, heat our lives, cook our food - even have food grown that we can eat - there would be no climate change. There also wouldn’t be 8 billion of us either and most human beings do rather like being able to live (that’s a testable proposition, the number who don’t equals the suicide statistics).

The fossil fuel billionaires are only such because we like to transport ourselves, heat, have and cook food and so on. There is no “other” forcing this upon us. It’s also true that there’s no solution to climate change - if one is even needed - without us out here changing our behaviour. Expropriating, eliminating, even topping on Tower Hill, those fossil fuel billionaires won’t change that in the slightest.

The entire system is based on our desire for the ability to drive off for a hot steak in a warm room. There is no “other”, other than us, causing it all. Nope, not even the Rosicrucians. Nor the Illuminati.

Climate change is not in the billionaires or the fossil fuel companies dear Brutus, it is in ourselves.

America’s Exceptional Experiment in Self-Government

I was very pleased to receive a new ‘think piece’ by Tom C Veblen — yes, he is related to the great Theory of the Leisure Class author, and his daughter worked at ASI for a while too. His piece is called America’s Exceptional Experiment in Self-Government and it imagines a cultural and political revival of that great nation, now struggling through its self-induced cultural and political mess.

Among other things, Veblen cites a guide for surviving a seaplane crash on water. When that happens, they tend to come to rest upside down, so you need to have your wits about you. You must stay calm. Grab your life vest. Open the exit and work out your escape route before releasing your seat belt. If the obvious way out is blocked, work out another before you unbuckle yourself. Don’t let go until you are out. If you are underwater, follow the bubbles to the surface. Then inflate your life vest.

Veblen says it’s an analogy for ‘getting out alive’ from the wrecked political systems we have, and the more you think about it, the more apt the analogy is.

You need to stay calm. Too many politicians see problems emerging — inflation, for example, leading to widespread complaints and strikes over pay, rising borrowing costs, falling house prices and soaring prices for essentials like food and energy — then rush into some ‘quick fix’ solution that actually makes things worse. Like huge domestic heating subsidies to households, both rich and poor, which require vast new public borrowing to finance.

Or windfall taxes on oil producers alongside calls to cap energy prices, which have the effect of driving energy investment out of the country. Or capping the price of bread and milk and other basic groceries, which (as the author of Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls can tell you), won’t work and will just lead to shortages.

No quick fixes will get you out of this crash. You need to grab your life vest, the thing that’s going to keep you afloat. And that life vest is what Adam Smith (whose 300th birthday we celebrate this month) called the ‘simple system of natural liberty’. Make sure your money is sound, protect the basic institutions of open markets, competition, individual liberty and the rule of law. Leave people free to go their own way, and they will collaborate and boost value and progress before any government bureaucrat has even got the spreadsheet functioning.

Then you need to work out your escape route. That’s not always easy, as we discovered during the early 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher’s government tried to roll back a bloated state. Efficiency experts were brought in, and when they left again, things reverted back to their sad normal. We needed instead to work out a way to get the all-dominating nationalised industries (utilities, communications, transport, manufacturing and all the rest) out of state protection and into the chill wind of competition. The solution to each was different, and some worked better than others. It’s not easy to find your way out of a crashed state.

Follow the bubbles — look at what other people round the world are doing that actually works, and do that, rather than clinging to some ideological totem pole like the National Health Service. And, when you have done all that, distance yourself from the wreckage and inflate your life vest. Deploy the system of natural liberty, and you can float free.

Something we actually agree with

John Naughton tells us that:

We got to the point of thinking that if all that was needed to solve a pressing problem was more computing power, then we could consider it solved; not today, perhaps, but certainly tomorrow.

There are at least three things wrong with this. The first is that many of humankind’s most pressing problems cannot be solved by computing. This is news to Silicon Valley, but it happens to be true.

It’s also news to all those who would plan the economy. Allende was one of those who fell prey to this delusion - computers were going to run that Socialist Chilean economy. But it’s been a phantasm all the way back to those first stirrings of scientific socialism. If only we could calculate then we’d be able to plan!

No, actually, we can’t. We do not have, cannot have, the information required to feed into the starting point of however much computing power we have available.

While Hayek was right here, an excellent outlining of the problem in detail is this. The most important part of which - after the intractability of the actual computing problem - is what is it that we’re trying to plan?

We want to optimise some form of social utility function. OK, so what is that? The sum and aggregation of all of the individual utility functions, obviously. So, what are they? Well, we don’t know. Because utility functions are something we back calculate. We observe what people do given what’s available then write that down. But if we have to observe behaviour in order to work out what people want then we cannot plan what will be made available as we don’t know what will maximise utility in that new situation created by the plan. We can’t just ask people because that’s expressed preferences and we know that doesn’t define utility - revealed preferences do.

Naughton is quite right, not all problems are amenable to more computing power. The direction and planning of the economy among them.

Britain doesn't have enough second homes

From Theodore Zeldin’s “The French” (1983):

Almost one in every six families has access to a second residence

Translate that into British, we’ve some 25 million households, there should be 4.25 million second homes.

According to George Monbiot we have rather fewer:

Before the pandemic, government figures show, 772,000 households in England had second homes. Of these, 495,000 were in the UK. The actual number of second homes is higher, as some households have more than one; my rough estimate is a little over 550,000.

We are, thus, short some 3.75 million second homes. If we wish to be like the French that is.

This is more than just snark - tho’ snark is always fun. The important thing to understand about housing across cultures is that each is a technology. A machine for living in. And those cultures, technologies, which have people living in dense urban cores, in apartments, also have the wide ring of summer places surrounding them. This is true - from personal experience of people here - for Germany, of the Czech lands, or Russia (to the point that one of us has endured a lecture from a Soviet car factory manager on the importance of providing dachas for the workers. And it was important, growing your own was the only way you’d get vitamins, let alone vegetables.) No, an allotment is not the same thing - it is illegal to even think about staying overnight on an allotment. All these country places will have at least a shack with bunks.

The Southern European towns tend not to have gardens attached even to the houses, let alone the flats. But they have different inheritance practices (real property must, by law, be divided equally among all kids) and are also several generations closer to the land. At least a part share in Granny’s hovel out in the country is near universally available.

Those stack-a-prole worker flats that our UK urban planners think we should all live in are only part of that whole housing technology. By observation that works only with that addition of the second place in pulchra agris. The British solution to the same idea, that housing technology as a whole, has been the des res with front and back garden and on that quarter acre plot of land. Exactly the thing that is now illegal to build given required densities of up to 30 dwellings per hectare.

They’re technologies. Suburbs of housing with gardens, or flats with second houses. They’re integrated technologies, things where you need both parts to make them work. Our British planners have decided to go off half-cocked with only half of either technology. They’ll allow the house but not the garden, the flat but not the shack in the country.

We might have mentioned before that we really don’t like planners or planning. This is one of the reasons why - the planners we actually get are ignorant.