Less lab space keeps us off the pace

The COVID-19 pandemic helped highlight our reliance on laboratories like never before.

The labs provided vital research into vaccinations, playing a vital role in overcoming the challenges presented by the pandemic. Even before that point, life science innovation has contributed to society in immeasurable ways. Including the development of antibiotics, the invention of gene editing techniques, and understanding the structure of DNA à la CRISPR.

In the UK, this innovation is largely concentrated in the Oxford-Cambridge arc, an area in which there is a distinct focus on academic research. Biotechnology companies buzz around this golden part of the South like bees to (profitable) honey, hoping to set up research laboratories across these cities due to their close proximity to highly intelligent science graduates who may go into research.

However, there is a colossal problem standing in the way of the continued development of vital research innovation. A problem so big that it could hinder the very safety of the British people come the next pandemic - a lack of lab space which handicaps the very research keeping us safe.

As shown on the graph below from the Financial Times, demand for lab space far exceeds available supply.

Sue Foxley, research director at Bidwells property consultants, explained in 2022 that,

“In June this year, Oxford had 18,000ft(sq) of lab space available for research-intensive SMEs, but the demand was vastly higher at 860,000ft(sq); Demand in Cambridge totalled nearly 1.2 million square feet, but the availability there was zero.”

With the UK unable to keep up with growing demand for lab spaces, we are at threat of losing potential innovation opportunities in the life sciences sector to cities such as Boston, where more lab space is available. We’re also at risk of a brain drain, forcing graduates from these research specialist universities to move further afield. Perhaps to another more attractive country.

You may hear people argue that we are fixing this problem by growing lab spaces in other parts of the UK, and indeed we have. In South Manchester for example, a £2.1 million deal has been passed, completing the sale of 10,000 sq ft of office space to convert into lab space. Similarly, in Edinburgh, 20,000 sq ft of space is currently being turned into lab space.

This is a step in the right direction but it doesn’t fix the problem in Oxford and Cambridge: the areas where clusters of innovative firms already exist. These innovation clusters, like the ones we see in Oxford and Cambridge, take years to develop. By building a series of lab spaces dispersed throughout the UK we would be missing out on agglomeration effects and thus losing out on the positive innovation opportunities that we see in Oxford and Cambridge.

How do we go about resolving this? We could repurpose existing spaces in Oxbridge into lab space. One way this could be done is by relaxing restrictions on Grade II buildings which take up a large percentage of all listed buildings in both Oxford and Cambridge (in Oxford and Cambridge there are 77 and 47 Grade II buildings respectively). While there is a reluctance to suggest this due to the ‘special interest’ these buildings have, due to the dysfunctional nature of the planning system, this seems like a necessary approach to ensuring an increase in lab space.

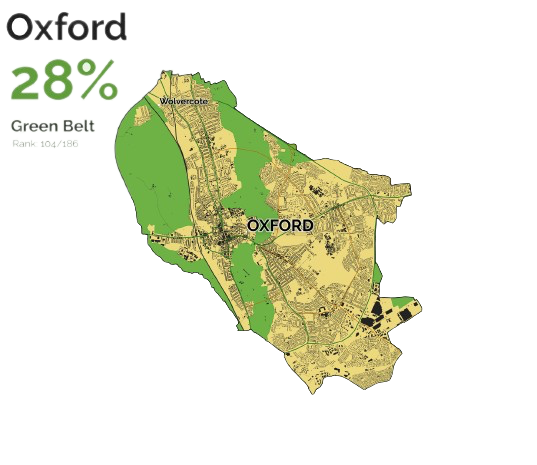

Another solution, as with the housing market in general, is to open up areas of the green belt for construction. Admittedly, Oxford and Cambridge are places with lower green belt areas in contrast to others in the UK, however there is still around a quarter of green space in both, as shown on the graphs above.

By extending construction into these areas, the supply of space available for labs would become much more readily available. Despite concerns that this ruins ‘picturesque’ landscapes, this largely isn't the case with more than a third of the green belt dedicated to intensive farming, an environmentally damaging process which leaves landscapes far from scenic.